in a film by Director Jerzy Kawlerowicz

Peter K. Gessner

|

More than a hundred years ago, in1896 to be precise, Henryk Sientkiewicz published Quo Vadis,

a great epic story about power, overcome by faith, about faith, which brought love, about love which

changed Rome. An incredible popular tale of early Christian glory and persecution at the hands of the

Roman Emperor, Nero, the book was translated into 48 languages and in the first year following its

publication sold more than 800,000 copies in France and Britain alone.

In 1905, on the strength of this epic, Sienkiewicz was awarded a Nobel prize in literature, the

Nobel Academy stating: "If one surveys Sienkiewicz's achievement, it appears gigantic and vast, and at

every point noble and controlled. As for his epic style, it is of absolute perfection."

In 1912, the story was made into a 120 minute film, the first feature film ever. It run for 22

consecutive weeks at the Astor Theater in New York City. In 1932, it was filmed again with a cast of

20,000, but that too was dwarfed by the 1951 MGM Quo Vadis super-super-colossal Hollywood

production directed by Mervyn LeRoy; 171 minutes long, it had a cast of 60,000 and featured a beautiful

interpretation of Nero by Peter Ustinov who received an Academy Award nomination for it. The film

proved so popular as to become exceedingly profitable, second only to Gone with the Wind in the history

of the cinema up to that time.

Sienkiewicz was noted for his inordinate ability to paint word pictures of places and events. Although there have been five English translations of Quo Vadis published in the United States, many Poles have felt none were fully successful in rendering faithfully the mood and feelings described by Sienkiewicz and that a similar concern applied to the screen versions. This view was one shared by the accomplished Polish film director, Jerzy Kawlerowicz who for 35 years has dreamt of directing a Polish version of the tale - and finally Poland's changed circumstance have made this possible.

A Clash of Civilizations

|

Kawalerowicz's, 2001 version of Quo Vadis, is the most expensive film ever made in Poland, and - as one critic put it - every penny spent is evident on the screen. Set in Nero's Rome, the film portrays, to use a phrase that has gained wide currency since September 11, a clash of civilizations. Here it's Imperial Rome, mighty, the dominant power in the then known world, unchallenged militarily and ruled by an intellectual, sophisticated and refined elite, which is challenged by nascent Christianity or what the Romans considered a rabble of servants and slaves. But the "rabble," is moved by a fervent religious faith, transmitted with love and untinged with skepticism. Fanatical in the eyes of the Romans, it's a faith which gives its adherents self-respect in this world and a promise of an incomparably better existence in the hereafter. It also renders them, thereby, ready to accept sacrifice and martyrdom.

Written more than a hundred years ago, Henryk Sientkiewicz's Nobel prize-winning novel achieved incredible popularity, selling, in the first year following its publication, more than 800,000 copies in France and Britain alone. Translated into four dozen languages - and with at least five separate English translations - it has been brought to the screen on five different occasions. One of these, a 120 minute version that run at the Astor Theater in New York City for 22 consecutive weeks in 1913, was the first feature film ever made. In 1932, it was filmed again with a cast of 20,000, but that too was dwarfed by the 1951 MGM Quo Vadis super-super-colossal Hollywood production directed by Mervyn LeRoy; 171 minutes long, it had a cast of 60,000. It proved so popular that it become exceedingly profitable, second only to Gone with the Wind in the history of the cinema up to that time.

|

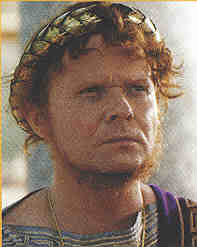

Kawalerowicz, who, with the aid of 32 lions and computer graphics achieves degrees of verisimilitude in the mauling of the Christians in the arena undreamt of in earlier versions, has produced a film that is particularly faithful to both the letter and the spirit of the novel. Its author, Sienkiewicz, was a man endlessly fascinated by the ancient Romans. Fluent in Latin, for years his bedtime reading consisted of the writings of Julius Caesar, Tacitus, Cicero and the like in their original Latin. Much interested in Roman archeology, he used their writings as guidebooks during his lengthy sojourn in Rome. As a consequence, his portrayal of Nero and Petronius, both historical figures, the latter a friend of the Emperor, an arbiter of taste, and in real life, the author of the worlds first novel, Satiricon, are anything but one dimensional. And it is the development of their characters and that of a Greek philosopher/low life, Chilo, that take pride of place in Kawalerowicz's film. Nero, though corrupted by the absolute power he wields, has a fine artistic taste and is no fool. Petronius, played masterfully in the film by Boguslaw Linda, is a skeptic unwilling to make judgments of good or evil, but intellectually honesty and daring. Craving excitement, he frequently engages in pointed verbal repartees with the Emperor, an inherently dangerous game, given the latter is a capricious all-powerful tyrant.

It is the third figure that of Chilo Chilonides, a Greek in equal measure philosopher and peddler of both his services and principles, that perhaps most fascinated Kawalerowicz. The Romans had subjugated Greece to their power, but sought to shine by its reflected light, paid lip service to its culture and former greatness, and sought the services of Greek sages. But a philosopher who has to peddle his principles to keep body and soul together is an oxymoron. As a consequence the figure of Chilo is simultaneously both the most detestable and fascinating one in the film. Well read in philosophy, he is nonetheless an inveterate liar, a blackguard who would sell his mother, passionate in his will to survive, yet able to rise to above these shortcomings and to exhibit a nobility of spirit when that might be least expected.

Petronius ( Boguslaw Linde) |

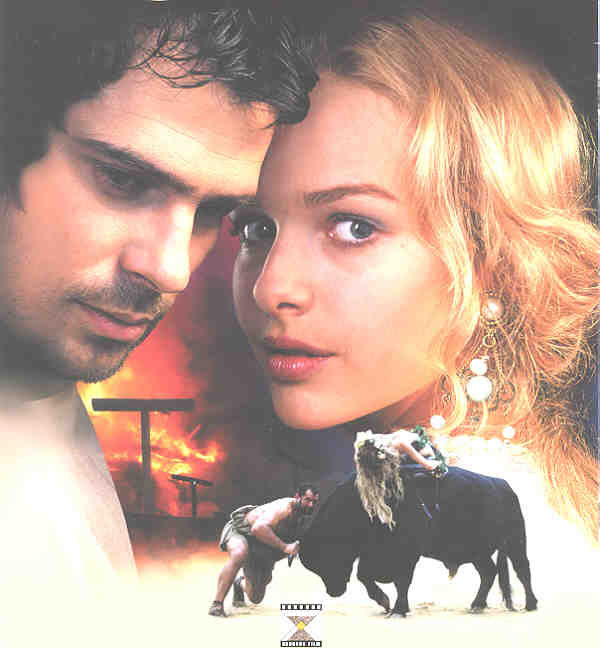

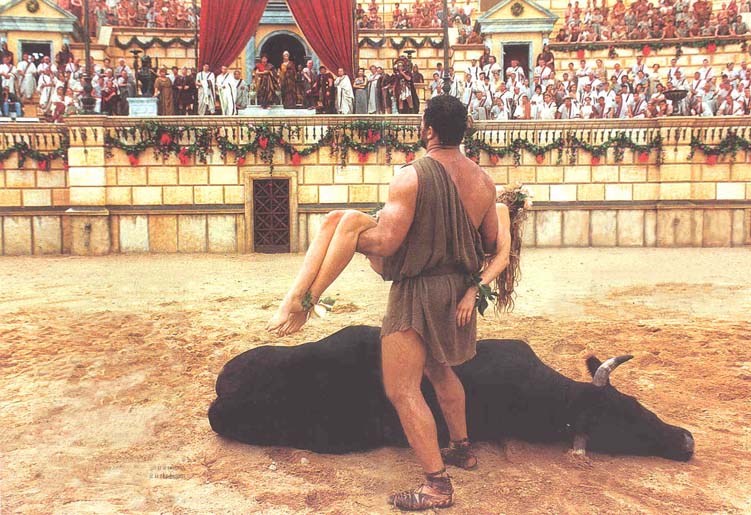

By weaving into the tale a romance between a ranking Roman officer and a foreign princess brought to Rome as a hostage who has since secretly embraced Christianity, Sienkiewicz and now Kawalerowicz provide us an opportunity to view both the world of the Christians and that of the Romans. Her romantic lead also serves one of the films climatic moments when the terrified young woman enters the arena tied to the back of wild bull and is saved by a giant of a man who wrestles the bull to the ground and breaks its neck. As for the title of the film, it derives from a legend that Peter, fleeing the persecution of Christians in Rome, encountered Christ walking in the opposite direction, asked: Quo Vadis, Domnine "Where are you going, Master?" "To Rome to be crucified again," the latter replied.

The Storyline

Quo Vadis is a story, as behooves a Nobel prize-winning novel, with an intricate plot, one well known to the members of Polish audiences most of whom have read the book. For those who however have not had that pleasure, knowing something about the story of the film will make it easier to follow its twists and turns, particularly for those who will need to rely on the film's English subtitles, since the film is in Polish

The opening sequence of the film shows two gladiators locked in a fight to the finish. The setting is Imperial Rome in 54 - 68 A.D., during the reign of Emperor Nero. Human life counts for little. Next, we are introduced at his home to one of the films chief protagonists, Petronius, a refined arbiter of taste, a skeptic, and a friend of the Emperor. He is visited by Marcus Vinicius, his nephew and a Roman officer. Vinicius has just returned from a campaign in Asia Minor. He confides to his uncle that, upon his return to Rome, he has fallen in love with a beautiful and mysterious girl named Lygia, a Ligian whom he has met in the house of a retired Roman military leader, Aulus Plaucius.

Wishing to help the young man, Petronius suggests paying a visit to the Plaucius' house. On their arrival, Petronius can see for himself that his nephew's enchantment is justified; he decides to help him. Meanwhile, Vinicius and Lygia meet in the garden, where the girl draws a fish in the sand. with a stick The young man, however, is so stunned by the girl's beauty that he doesn't seem to notice it.

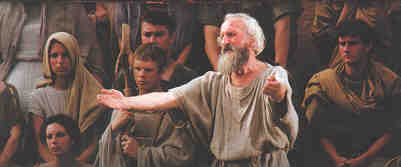

Vinicius( Pawel Delag) |  St. Peter and Ligia (Magdalena Mielcarz and Franciszek Pieczka) |  Nero ( Michal Bajor) |  Chilo Chilonides( Jerzy Trela) |

Two days later,. Lygia is escorted by the Emperor's Praetorian guard to his palace. As the daughter of the Ligian King, she is to be kept under the Emperor's supervision. When Vinicius hears about this from Plaucius, he is enraged. However, Petronius tells him that this is but a ploy that will make it possible for Lygia to be soon conveyed to Vinicius'es house.

In the Emperor's palace, Lygia is groomed by Akte, Nero's former mistress, for a great feast in the Emperor's honor. At the feast, Lygia is quite impressed by the glamour surrounding her but enchantment vanishes when Vinicius, drunk, harasses her. She is rescued by Ursus, her faithful servant, an amazingly strong, athletic Ligian who spirits her from the feast, leaving the inebriated Vinicius unable to follow. Next day, Lygia, is being fetched by Vinicius'es servants but, mirablile dictu, ends up instead among the followers of Jesus Christ.

Vinicius, in despair and rage, wants to find the Lygia at all costs. Again, his uncle, Petronius, offers his help. He dispatches Chilo Chiloides, a Greek to find Lygia. Chilo is convinced that Lygia has found refuge among the Christians. At the same time Nero's daughter dies and Lygia is accused of having killed her because, during her stay in the palace, she had cast her eye on the little girl in the garden. Petronius, who wants to protect Lygia from danger, suggests that Nero, and his court, go to the Imperial summer residence in Ancium.

Meanwhile, during the night Vinicius accompanies Chilo and Kroton, a famous gladiator, to an old graveyard in Ostrianum where the Christians meet. There they spots Lygia with Ursus and decide to follow them.. Vinicius, with Kroton's help, tries to take possession of Lygia but is struck unconscious by Ursus' powerful fist. He comes to in a Christian house, and there encounters Lygia. He discovers that she shares his feelings of affection. However, Peter the Apostle advises Lygia to avoid Vinicius unless he embraces her faith.

In vain, Vinicius tries to forget Lygia. Unable to do so, he decides to seek out Paul of Tarsus to whom he tells of his affection for Lygia, of his doubts and his wish to be joined with her in the Christian faith. Lygia is sent for and the young couple is blessed by Peter. Vinicius goes to Ancium to be at the Imperial court, leaving Lygia behind in Rome.

Nero, still in Ancium, recites and is much taken by a poem about the burning of Troy. Soon Rome is set on fire. Vinicius, now in Ancium, hurries back to Rome to search for Lygia. He runs into the Greek, Chilo who leads him to the place where the Christian have found shelter. It is there that Vinicius is baptised by Peter the Apostle.

|

On Nero's orders, the Christians, accused of have set fire to Rome, are to be sought out and punished. The Roman mob is promised spectacular Games during which appropriate punishment will be inflicted upon the Christians. Petronius, having gotten wind of this, tries to warn Vinicius, but it is too late, Lygia has already been taken into custody. She falls ill and ends up in a coma. Vinicius persists to make efforts to get her out of the prison, but to no avail. More and more Christians die in the arena.

It turns out that Nero has devised a special spectacle for the closing of the Games. Lygia is to be spectacle's main attraction. First Ursus is made to enter the empty arena. Then a wild bull, with a beautiful naked woman tied to its back runs into the arena. The woman is Lygia. The odds seem uneven, yet, by a supreme effort, Ursus manages to brake the animal's neck. The crowd goes wild and cries "Mercy!". Much against his will, Nero feels forced to set Lygia and Ursus free..

Vinicius takes Lygia out of harm's way to Sicily. Before departing, he advises Peter to flee from Rome as soon as possible. Peter follows his advice but on his flight meets Christ and asks him: Quo Vadis - where are you going. To Rome to be crucified again - Christ answers. Shamed, Peter turns around to bo back to Rome and martyrdom. Petronius, knowing that he Nero will impose a death sentence upon him, commits suicide. There is a mutiny among the Gallic legions. The Emperor Nero has to die.

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |