|

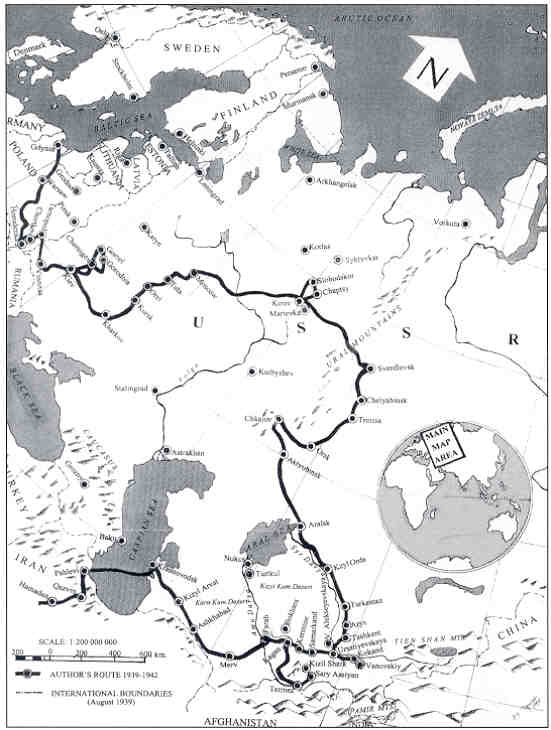

I don't remember leaving Kirov. It must have been during the night because when I woke up we had already passed Molotov and were heading east towards the Ural Mountains. Sleeping sitting up is never comfortable, especially when you cannot stretch your legs. For a while I was considering sleeping on the floor under the bench, but the dirt and dust there were so bad that I gave up the idea. Nonetheless, a few men, whose standards of cleanliness and hygiene were even lower than mine at that time, went ahead and slept there anyway. A witty newcomer promptly dubbed their sleeping area "Wagon-lits Orient Express." He was one of the two brothers chosen by Sergeant Zolotnicki to complete our unit.

The Pikesfeld brothers stood out from the rest of us because of their quality clothes and their voluminous and elegant luggage. They were in their twenties and in excellent physical shape. They were from Cracow, which they had left in a hurry to flee from the advancing German army, and landed in the Soviet-occupied half of Poland in 1939. From there they were exiled by the Communist regime to a small northern village near Syktyvkar in the autonomous Komi Republic, land of tundra and reindeer. They lived there not so much by toil and sweat as by bartering their valuables, clothes and trinkets with the natives for food. They still had their pre-war Polish passports and also valid immigration visas for Australia. It was obvious that they treated joining the Polish Army as a stage in their journey from the land of Northern Lights to terra firma under the Southern Cross. Both of them were well educated and intelligent. The younger brother was musical and whistled all day long the tunes and melodies from his vast repertoire of classical music. Money seemed no problem for them and they often bought extra food at exorbitant prices. Outgoing and with a good sense of humour, they mixed well with most passengers.

Sergeant Zolotnicki was addressed by most of us as Szef (Chief)--although that title in the Polish Army was rightly reserved for company sergeant majors. The sergeant brought some semblance of military routine to our car. There was reveille at seven in the morning, then half an hour for a pretence of washing ourselves with a cup of water from a bucket prudently purloined from a firemen's equipment room in the Kirov railway station. Those who had a razor, the will and the need--I still had no beard worth mentioning--would also shave. Then everybody stood up and Chief intoned the "Our Father" and "Hail Mary" prayers followed by us all singing the traditional morning hymn, "At dawn all lands and seas sing praises for Thee, God Almighty" The Pikesfelds, although Jewish, sang it along with us but as praise for Yahweh. In these turbulent times atheists were few and far between. Chief, who had a deep and sonorous baritone, could turn an indifferent crooner into a real songster just by staring at him and by singing crescendo until he got the right response. He also led our singsong sessions far into the night. We sang the songs we learned as children at home or at school; Boy Scout songs; popular folk songs; dozens of army marching songs, some of them going back to the seventeenth century; wistful bivouac songs; bawdy songs and tavern songs; well-known waltzes; and mushy tangos. The sessions ended with everybody standing up for a solemn rendition of the patriotic hymn, "We'll not forsake the land of our roots"--the hymn the onlookers and prisoners sang at the Tarnopol station when we were loaded onto a Soviet train taking us out of Poland.

After morning roll call, Chief would name the men responsible that day for clearing frozen feces from the brake platform at the end of our car, bringing fresh water, or delivering coal for the stove. Everybody knew that "delivering" meant stealing, either from a heap of coal at a railway station or--which was more common--from the locomotive tender. Bringing the coal was tricky. It took two men to find the coal, to negotiate with the guard or to divert his attention, to load the sacks and to bring it home. The driver and the firemen of a locomotive would usually turned a blind eye on a man climbing the tender and throwing down large chunks of coal to his mate below. But the guards, militia or soldiers sometimes took their duties seriously and raised Cain, forcing a "deliverer" to flee. Moreover, any nosy railway official who had a bad day or suffered from indigestion could spoil a well-planned "delivery."

We hardly noticed that our train was passing through the Urals. Instead of awe-inspiringly high mountains dividing Europe from Asia, all we saw were some snowy hillocks crowned by anemic looking spruce trees. The next station was Pervouralsk and soon we were in Asia. The crossover was quite a letdown, best summarized by a Corporal Zuk. After a short visit to the station's latrine, he declared, "Gentlemen! I just had my first crap in Asia and it was no different from Europe. Take it from me."

Our train was carrying us toward the former Yekaterinburg, renamed Sverdlovsk by the Soviets for the Bolshevik commissar who executed Russia's last tsar there in 1918. I seldom ventured out of the train. The 1941--42 winter was unusually cold. When we reached Sverdlovsk the thermometer fell to 50?C below zero.

Chief took pity on me, the youngest and the smallest, and excused me from any outdoor duties during that arctic spell. Our stop in Sverdlovsk lasted two days. On the first day of our stay there, a political commissar who stood on the railway platform overheard some of our men talking Polish and shouted, "Poles?" When we nodded, he jumped up the steps, opened the door of our car and waited until the din of forty yapping men stopped. Having caught everybody's attention, he made a three-word announcement: "Sikorski's in Moscow." General Sikorski was at that time the leader of the Polish government-in-exile in London. Saint Peter opening the gate of the kingdom of heaven and announcing the visit of a redeemed Lucifer would not have had more impact on the angels than the commissar's news had on us and on the average Soviet citizen. In order to avoid any questions, which could have led him into a political minefield, the commissar saluted and vanished as quickly as he came. The following day we read on the front page of Izvestia a communiqu?about the Sikorski-Stalin meeting in Moscow. Apart from the usual platitudes, it mentioned the Polish Army in the USSR. It gave no details about its whereabouts but, even so, it boosted our morale. The goal of our journey now seemed less hazy and less remote.

At Sverdlovsk, the Trans-Siberian line turned south as far as Chelyabinsk before turning east again. But there our train would turn off the Trans-Siberian line to continue hugging the eastern foothills of the Ural Mountains, carrying us southward to where the Polish Army was being regrouped, or so we hoped. On the second day in Sverdlovsk, we lost two of our companions. One was seen with all his belongings boarding a northbound train standing on the neighbouring track. We never knew why. Another one failed to answer the morning roll call. He was found dead under the bench, his usual sleeping place. He was a quiet man in his fifties. Nobody would have missed him if it hadn't been for our daily roll call.

The body was carried out by a second pair of brothers in our group, the Dombrowskis, who volunteered for the job. When they returned from that impromptu funeral, they told us that there was a large pile of frozen corpses behind a railway shed and the stiffs were to remain there until spring thaw, awaiting burial. The dead man's bundle and the contents of his pockets, as well as his documents, which had a high black-market value, were considered to be a fair honorarium due to the brothers for performing the last rites.

News about the death of that man spread to the other cars. In our train there were two or three heated boxcars carrying families of farm people who were also hoping to meet up with the Polish Army. They had been deported in 1940 from their homes in Poland to the miserable Siberian kolkhozes. They were victims of the so-called free-resettlement scheme, a Soviet plan to disperse and weaken what they called "unreliable and socially dangerous elements." These "dangerous elements" in the car next to ours were mainly women with their children and aged men heading south in quest of the Polish Army, which, they believed, would take care of them. We had little contact with them. There was no direct passage between the passenger car in which we travelled and their boxcars, which were entered by sliding doors on the sides and so were accessible to us only when the train stopped. As far as I know, nobody from our car ever went to see and talk to these "civilians." In cold that froze our spit before it hit the ground, nobody wanted to stay out even a minute longer than was absolutely necessary. Besides, every one of

us was too much of a coward to confront those starving and wailing creatures without being able to offer them some help.

But during a stop, two of the boxcar passengers paid us an unexpected visit. Both were men. One introduced himself as Father Krol, a thirtyish Catholic priest who had somehow managed to conceal his true identity from the Soviets for two years while working as a farmhand on some faraway kolkhoz. The second man, Franek, who was much younger, was his acolyte. Father Krol regretted that nobody told him about the man who had died under the bench and that he had been unable to say the requiem for him. Then he talked about the stark conditions of the people in the boxcars and their expectations of miracles that would save them. In the end, Chief Zolotnicki wound up offering the priest and his acolyte the two free places in our car. They accepted readily and within minutes they brought their few belongings and settled in, looking very happy.

The Dombrowskis were poles apart from the Pikesfelds in every way. They were professional thieves and looked alike. Both Dombrowskis were in their late twenties, short and squat with dark hair starting about one inch above their eyebrows. When they talked to somebody they would constantly shift their eyes, watching the space first beyond one ear and then beyond the other of the person they were facing. Nothing seemed to escape their surveillance. They spoke the overblown language of trashy novels, but occasionally a word from thieves' cant would slip in. They parried questions about their past with a grin and sayings like, "Wouldn't you like to know?" or, "Who can remember that?" All we learned from them was that they came from central Poland and spent a year or so in the tough Ukhta-Pechora labour camps in northern Russia.

There was a third man called Adam, who had joined our group with the Dombrowskis. They sort of adopted him, if one can adopt a six-foot hulk. He was a kind and slow-thinking fellow, impressed by his suave and artful new pals. It took him a long time to find out that they were thieves, though they kept using him as a decoy They would make Adam keep a place for them in a bread line while they themselves queued well behind him and carried on a nonsensical conversation with him by shouting. This attracted the attention of the people in the line who were particularly bemused at the look on Adam's face, for he was genuinely perplexed by the absurd questions thrown at him. At the same time the brothers "worked" the pockets and bags of people around them. After that, they would slip the stolen rubles, penknives and cigarettes into Adam's coat pockets. He carried these to the railway car without knowing it, leaving the Dombrowskis "clean" in case they were arrested and searched by militia. He also carried their coal, which they "bought" from the train driver. Adam was strong, trusting and naive.

At one station, the brothers brought in some heavy planks with which they built themselves a mezzanine sleeping platform which was supported by the baggage racks. Now they could sleep comfortably above us with their legs stretched out. On the whole, they were friendly and helpful to us, but one day the Pikesfelds' passports with their precious Australian visas went missing. The Pikesfelds paid a gold coin to the Dombrowskis as a reward for "finding" the passports.

At the next long stop, Chelyabinsk, the Dombrowskis hopped off the train even before it came to a full stop. They came back in high spirits, cradling a bottle of vodka and carrying--almost in mid-air--Galya, an apple-cheeked, buxom hoyden.

Nobody knew what to say about this new addition to our car full of men, so we said nothing. The Dombrowskis installed her on their deck, which was above our eye level. She spent all her time there between the two brothers, climbing down only when she had to go out and that was mainly at night. Every time she crossed the car, forty pairs of eyes escorted her to the door and back to the upper deck. Even when our thoughts started drifting to other things, a muffled giggle from the platform above would shortcut them back to the Siberian Circe. If anybody among us was really bothered by her presence, it was our newly acquired spiritual leader, Father Krol.

Pikesfelds' largesse for the return of the missing passports had changed the lifestyle of the Dombrowskis. On every station they would buy moonshine, bread and onions at black-market prices and stow these luxuries on their upper deck in front of their protégée. Both brothers drank heavily and, following the Russian custom, would strip naked during their binges. Their feeble attempts at singing usually ended in bouts of retching. At times they would become belligerent and spoil for a fight.

At one of the small stations, the Dombrowskis returned from their prowl full of excitement. "We need a few men to help us right now. We've found a real treasure. We promise you a feast tonight!"

The entire car crowded around them eager to hear the details. It appeared that on one of the cars of a train with military supplies they had spied a whole load of cases of canned food. The train was on one of the tracks not far from ours, but it was protected by a sentry However, as it was nighttime there was less risk of being caught.

"How do you know there is canned food in these cases?" asked the older Pikesfeld, the skeptic.

"I can tell a case of soldiers' grub when I see one. They are a special shape, and the colour is different. Don't go if you don't want to. Besides we need a man with brawn not brains. Come on, Adam! We need one or two more." They took Adam and two more guys. Galya went with them as a decoy to distract the soldier on guard.

They came back triumphant. Adam, the mule, was bent double carrying the loot on his back. Drops of sweat were dripping from his brow. When the wooden case was pried open our circle of onlookers gasped in unison.

Inside, neatly arranged and protected by wood frames, were artillery shells. We were not disappointed: we were terrified. For stealing army food you could get five years, but for stealing ammunition the penalty was death. The dozen or so shells had to be taken away one by one behind the station and thrown down the latrine hole. A dozen risky trips. When the danger of being caught had passed, the Dombrowskis took a lot of ribbing about the feast they promised. But they didn't think it was funny They were grumpy and vented their bad humour on Galya, giving her a black eye for carrying out her task of distracting the sentry with far greater zealousness and enthusiasm than was necessary

Father Krol had taken over from our Chief at leading morning prayers. He lengthened them considerably and usually ended with a short sermon. The Dombrowskis' frolics got under his skin and in one of these little morning lectures he threw a few jabs at those who "practise an unhealthy familiarity that poisons the atmosphere of the entire car."

The elder brother was lying on their deck with his head propped up by his elbow and listening to the homily. He was stung by the priest's allusions to his conduct. "Father, it's easy to preach a clean life for someone like you who tied a knot on his peter and carries his nuts around for display only But for us, mere normal mortals, living clean is well nigh impossible. Somebody's got to sin, if only to keep your job going."

Father Krol pretended he didn't hear it. So did the rest of us. The last round had gone to Dombrowski, but we weren't sure who was right. The veil of ambivalence hung heavily over the whole car.

A few days passed. All of a sudden the Dombrowskis lost their aplomb. They became gruff and even between themselves talked in monosyllables only Then they took Chief into their confidence and had a long chat with him, embellished by a lot of nods on both sides. They quit drinking vodka and developed a distaste for liquids as if suffering from hydrophobia. For them urinating had become an ordeal.

At the next station Galya was kicked out by the Dombrowskis without so much as a goodbye peck on the cheek, and the brothers were told by a nurse at the First Aid Post that Orsk was the closest place to get treatment for clap.

Over the next few days the pair turned into male vestals, poking and staring sadly at the fire in the coal stove. A few seats away Father Krol sat with his eyes raised to the dirty ceiling. With his hands clasped on his belly, he rotated his thumbs around each other, changing often from forward to reverse gear. He looked totally engrossed in pious contemplation except for an almost imperceptible smile on his lips.

The news about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was greeted with jubilation by us and the Russians alike. With the Yanks now on our side, we had no doubt that we could beat Hitler. But when we read that Roosevelt said America would produce 50,000 military planes in 1943, we thought it mere propaganda. Nobody could do that. Well, they did. And more.

But from day to day our lives were less affected by the big news and world-shattering events than by news of a bread store being shut; a railway line closed for three days to all non-military trains; or a friend left behind because a train left early without warning. I remember Chelyabinsk not for the glow of the iron smelters and steelworks, nor because it manufactured more than 50 percent of all Soviet tanks during the war, but because of the thin soup with a couple of slices of liverwurst floating on top of it that was being sold in the station buffet. I remember buying eight bowls of that soup, throwing out the liquid and then eating the slices of grey sausage. A princely feast.

It was the daily ration of bread that kept us alive during our train journey south. At almost every railway station (or close by) was a bread store. Some of them, at so-called evakopunkty (evacuation centres), distributed bread for civilians being cleared from the war zones; others were for military personnel. Strictly speaking, we did not belong to either category Our communal railway ticket was issued for "Polish Citizens repairing to the Polish Army," so we tried to wheedle out bread rations from both. Even with plenty of chutzpah we were not always successful. Corporal Zuk was our best trump card when dealing with a reluctant or suspicious breadstore manager. Although of short stature, he had an air of self-confidence and a gift of the gab that confused his adversaries, who would give way to the torrent of his ingenious arguments. While speaking he would thrust his foxy face into the face of the man he was talking to, forcing him to step back. This physical retreat was the first step in demolishing his opponent's ego. The rest was easy Zuk not only looked and sounded aggressive, he was aggressive. Even the muscular Dombrowskis would give him a wide berth.

In Troitsk, after we had collected our bread rations at the evakopunkt, Corporal Zuk rushed back to our car panting and yelling, "Out! Out! All of you. On the double."

We could sense the urgency in his voice and in an instant we were on the platform wondering what had come over him. He

stood on the top step of the car, two empty burlap sacks (one of them mine) folded over his arm saying, "There's no time for explanations. Just do what I tell you." Then he began yelling like a professional drill instructor.

"Form in twos! Right turn! Forward march!"

Running to the head of the column and passing our chief, Zuk gave him a reassuring pat on the shoulder as if saying, "Don't worry. I am not after your job."

"One, two! One, two! Left, right! Left, right!" He marched us to the back of the station and with a booming "Halt!" stopped us in front of a military store. The door of the store was wide open, and we could see inside it lots of boxes and sacks stacked on shelves. Near the entrance was a counter with scales and ledgers. A young lieutenant perching on the counter looked with curiosity at our unit and at its commander, who approached him, saluted and reported.

"Citizen Lieutenant! Commander of the platoon reports his unit on the way to the Headquarters of the Polish Army, ready to collect provisions."

Again Zuk saluted smartly, beckoned at Chief asking him to produce the railway ticket and ordered two men from our group to come closer. He handed over to them the empty sacks, yelled at the rest of us "At ease!" and, assuming a waiting stance, started picking his yellow teeth with a thin splinter of wood that he had pried from the counter.

The young lieutenant, looking confused, stammered, "Yes, yes. But let me check first at the office upstairs."

Fool! When he returned a few minutes later it was Corporal Zuk who was standing behind the counter counting the loaves of bread and weighing sugar on the scales. Zuk even found a packet of fishfat margarine. At the same time, with a stub of a pencil he was entering the quantities in the open ledger.

While the lieutenant stood speechless, Zuk shoved the loot in the sacks held open by his temporary subordinates. He signed the ledger with a flourish. With a broad smile he saluted the lieutenant who stood open mouthed, watching Zuk and his platoon marching away

"One, two. Left, right." The troop marched faster and faster and, once it turned the corner of the station building, broke into a wild, unmilitary run.

Another bread bonanza came a few days later. One of the Dombrowskis saw me sketching a snowy landscape with my pen and ink. He watched me for a while, then shook his head. "How can anybody draw a line like that without a ruler?" He pointed to the telephone poles and wires on my drawing. I tried to explain to him that the lines were not as straight as they seemed to be and with a bit of practice anybody could do it. But he wasn't listening. His mind was already clicking over as he stared and scratched his chin.

Our train stopped next at a small station. We were shunted away from the main tracks. Then with the clanking of chains and bumpers our engine freed itself with a shudder that rattled through its retinue of passenger and boxcars. It lurched forward and, gathering speed, shrank itself into a smoky exclamation mark on the horizon. Within minutes it whooshed past us heading the other way on a parallel track, greeting our stares with two scornful hoots. This was going to be a long stop.

The thieving brothers came back from scouting and winked at me to come outside. On the platform we three went into a huddle. They had a bread talon for two persons, a chit issued by the store clerk who verified identity cards. The talon was a cigarette-boxsized piece of stiff brown paper with a large black numeral printed on one side for the number of portions and a date stamp on the other side. With that you went to another wicket where the bread cutter would cut, weigh and hand over the bread. That was the usual procedure at many bread stores.

"Take a good look at this talon, artist," said one of them. "Could you with your pen and ink change 2 to 202 portions?"

Yes, I could. But I told them that 202 portions would never work. That was far too much. Twelve, maybe. That would be plausible.

"Penalty's the same for 12 and 202," they argued. Finally we agreed on 22. I would change the talon, but I would have nothing to do with getting the bread from the store. My share of booty would be five portions. "Agreed?"

"Agreed."

That evening I ate two kilograms of bread at one go. Only a man who has starved for two years would believe it. The remaining portion I exchanged for a piece of yellowish fat of unknown origin.

One of our fellow travellers was a former public prosecutor named Godlewski. He was a retiring, shy and frail-looking individual. At times I saw him talking quite animatedly to a colleague, a court martial judge named Wojciechowski, but with the rest of us he would just exchange polite greetings and a few words for basic questions and answers. It was not surprising that the Dombrowskis were not too well disposed to their natural adversary They were quick to notice that the public prosecutor would volunteer to bring water, to wait in a bread line to collect our rations or to clean the car, but somehow he avoided ever "delivering" coal for our stove. The brothers made frequent loud allusions to "His Honour" who shirked his communal duties. At one of the larger stations the needling became unbearable for Godlewski. He grabbed the burlap bag, hopped down the steps onto the platform and strode toward the coal shed.

Within minutes somebody in our car spotted him on the platform, this time being marched between two militiamen. Slung over his narrow shoulder was a sack with a few lumps of coal. I ran outside along with the judge, the Pikesfeld brothers and another fellow. We saw Godlewski and his escort go into the station building. The elder Dombrowski joined us. He now had unwonted pangs of conscience and ran in front of us, barring our way with stretched arms.

Public Prosecutor Godlewski arrested for stealing coal

|

|

"Gentlemen, allow me! I put that judiciary arsehole--who with all his education and intelligence cannot filch a couple of coal lumps--in this shit and I am going to get him out of it."

We found a small room with a glazed door which the militia used as their office. Inside we saw the two militiamen questioning our prosecutor. They checked his documents and took a few notes. Then they pointed at a chair and at the wall clock as if saying, "Sit here. We'll be back in one hour." And they went out leaving the office door half open.

We rushed in. "Quick! Quick! Take your coat off. Here, put on mine so they won't know you. Hurry up! Give me your hat and put on his cap. C'mon! Let's go!"

Public Prosecutor Godlewski looked at us but didn't move. He jerked his arm free from Pikesfeld who was trying to pull him out of the office. He dug his heels in and clutched the edge of the table he was sitting beside.

"Gentlemen! Please go and leave me alone. Can't you understand? I, a public prosecutor, was caught stealing coal. I was arrested and formally charged with theft. I am not going to break the law again by escaping. If you want to help me, please bring my bag from the car and leave me here."

We all thought that he had gone out of his mind. Judge Wojciechowski pleaded with him to leave. He mentioned something about extenuating circumstances and duty to one's country but to no avail. The Pikesfelds were also trying to persuade him to get out. "Nobody will ever forgive us if we leave you here."

In vain. He looked at us coolly, almost with contempt. He wiped his fogged-up glasses with the remnant of a handkerchief and waved us off with an authoritarian gesture as if dismissing a gang of unruly spectators from his court. He stared down Dombrowski who seemed ready to drag him out of there by force. Then the younger Dombrowski rushed in. "Come on! The train is about to leave."

So we left him there. While we were trotting along the platform back to our train, the elder Dombrowski explained it for his brother.

"You see? His brains got fucked up from fear."

Not far from me on the opposite side of the car sat a thickset man, completely bald. He was about fifty years old, always clean shaven and, as much as his well-worn clothes would allow, neat in appearance. He wore steel-rimmed glasses. Clips from a fountain pen and a pencil protruded from his breast pocket. I cannot recall his surname but it was one of those surnames in which substituting one vowel would change it from a Polish name to a Ukrainian name. But his overly correct pronunciation of the Polish nasal vowels "a" and "e," combined with a strong differentiation between the "h" and "kh" sounds, betrayed his Ukrainian origin. All these nuances of

speech would be lost on most Poles from central and western Poland (including my mother), who could not hear any difference between these sounds.

He was well educated and under his bald dome there was a concise encyclopedia of important facts and dates. In the middle of somebody's story he would interrupt to set the record straight. "Permit me to make a small correction, gentlemen. It was not one of the Karageorgevic but General Potiorek who said it in 1914."

He gave the impression of being a lawyer, or more likely, a highschool teacher, for he insisted on helping me with the English alphabet in my primer. But he always saw to it that the bucket was full of water and would sweep the car floor or remove the ashes from the stove even when it was not his turn. He must have been aware of the animosity that has smouldered between Poles and Ukrainians for centuries and he was doing his best not to let it flare up in our micro-society.

Then an unexpected thing happened. One afternoon the elder Dombrowski turned to my teacher and said loudly so that everybody could hear: "Listen, Baldy! I've been watching you for a long time. You detest all of us because we are Polish. Every time we sing, 'We shall not forsake the land of our roots' you cringe and you clench your teeth and your face goes red like a beetroot. Get out of here at the next stop, hrytiu [a derogatory nickname for a Ukrainian peasant]. We don't want to see your snout again."

Nobody said a word, not Chief Zolotnicki, not me, not even our priest. The Ukrainian packed his small plywood suitcase and tied it up with a string. At the next stop he slipped out of our car. We heard a short whistle and the train started moving. The incident was never discussed or mentioned again.

Our car could be entered from one end only. The glazed door at the other end was locked solid and the little platform leading to it faced the blank wall of the boxcar in front of it. It was on this little platform where we saw one day at dawn the outline of people standing there. The glass door was covered with a thick layer of ice, and we could not see clearly how many or who they were. Standing with their backs to our car door and lashed by the freezing wind rushing by our speeding train, they could not hear us banging at the door and tapping the windowpane. We knew they must have got on at the last stop, which was around midnight. "Are they still alive?" we wondered. Or were these now frozen corpses with their hands welded onto the handrail?

The train stopped and we ran outside prepared to see the worst. Well, there were three of them. Not quite dead but not far from it. They were like ice statues dusted with snow which smoothed the folds of their clothes giving them the look of formalized sculptures. Icicles hung from their beards, moustaches and eyelashes. They could not speak and they had to be helped into our car. We sat them around our blazing stove. When their lips started thawing they told us that they had missed their train and got separated from a Polish group like ours heading for Buzuluk, a town near Kuibyshev (Kuibyshev has now reverted to its pre-revolutionary name of Samara). According to them, Buzuluk was the new headquarters of the Polish Army in the USSR. When they saw our train leaving the station, they hopped on the platform of our car. They kicked the locked door and banged on the ice-covered window, but we did not hear them over the rumble and din of the moving train. They stayed with us only to the next stop, which was Orsk.

At Orsk, men from our group who went to reconnoitre the station found a representative of the Polish Army. His main task was to stop any Poles from going west to Buzuluk. The recruiting centre there was being wound up, he said, and all Polish units there were being moved south. Several new recruiting places were to be opened soon in Uzbekistan and all new transports were being directed there. No specific locations were given. In fact we saw on one train a unit from the 5th Polish Infantry Division on their way to Dzhalalabad somewhere near the Chinese border. Everything was in flux.

The three frozen men decided to ignore the recommendations of the Polish Army representative and boarded the first train going west in the direction of Buzuluk. So did about half a dozen other men from our car. As we eventually found out, their choice was right. It saved them weeks, if not months, of hungry wanderings through Soviet Central Asia.

One more man died in our car as did one in the neighbouring boxcar during our stay in Orsk. The Dombrowskis, who took the corpses to the outdoor morgue, came back cursing and swearing. They had to carry them a long way, yet somebody else had emptied the pockets of the stiffs before the brothers got hold of them. "Don't ask us to do it again! You can do it yourself. We are not running a charitable funeral business," they fumed.

That day we heard about another pile of frozen corpses. Wheelerdealer Corporal Zuk and his pals told us that, when they went to steal some coal, they saw a train passing slowly on a far track away from the station. It was a long train made up mainly of open flatcars but with a few boxcars with searchlights on their roofs. On the flatcars were German prisoners of war, standing, sitting or lying. Most of them were huddling together in small groups. Some of them wore army coats, a few of them just jackets and trousers. As the train moved off, some of the prisoners pointed at their bellies and mouths showing that they had nothing to eat. It was one of those December days which was 40°C below and windy. On every second or third car was a Soviet guard toting a machine gun. On the last flat car, there was a pile of dead Germans encased in ice. The guards poured water on the corpses so they would not roll off the car. At the end of the journey the bodies would be proof that nobody had escaped. Zuk and his friends asked a railwayman where they were taking them.

"Devil knows. To some faraway place," he said. "Far enough to make sure that all the Fritzes will be dead before they get there. Serves them right. We didn't ask them to come here."

Corporal Zuk and his friends had been hardened by their time in labour camps, but I could tell from their faces and voices that even they were appalled by the enormity of what they had seen--cold, planned murder by exposure.

|

ALEKSANDER TOPOLSKI was born in 1923, the youngest of three children. He grew up in Pruzana, in the Pripet Marshes of eastern Poland, and in Horodenka, a small town in the country's southeastern corner. Following two years in Soviet captivity, he joined the army loyal to the Polish Emigrée Government in London. A graduate in architecture from Manchester University, he practiced in England, Connecticut, Virginia, Puerto Rico, and the West Indies before settling in Canada. He has three grown children and lives with his wife, Joan Eddis, in Chelsea, Quebec.

|

Published by Steerford Press, South Royalton, Vermont - www.steerforth.com;

Price $16.00 Excerpt reprinted by permission.

www.withoutvodka.com

|

|

| |