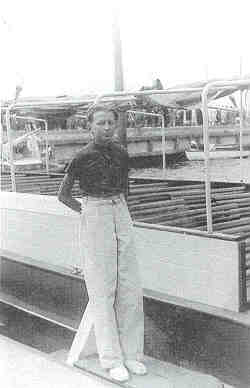

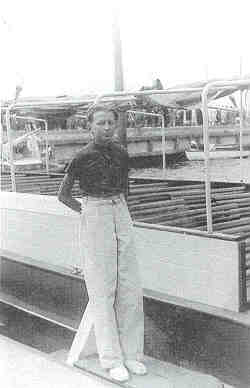

Topolski, 16, at Gdynia on the Baltic Sea during a boy scout trip in July, 1939 |

After my return I hardly had any time to gloat and boast about my exploits on the shores of the Baltic--in two days I left for the Boy Scout camp in the eastern Carpathian Mountains. But striving for proficiency badges and singing around the campfire had lost the attraction they once held for me. At sixteen I thought myself too old for all that. Instead I thought about the new tennis court at our high school, about my new, long white linen trousers, and my older friends who were passing their vacation time at the municipal swimming pooi in the company of young women, dancing inept tangos with them in the evenings on the pavilion terrace and afterwards walking them home. Within a week I found some feeble excuse to leave the camp, and I returned to Horodenka.

Every day that August the newspapers and the radio brought foreboding news about Germany's latest demands and threats. Hitler felt confident that he could walk unopposed into Poland as he did into the Rhineland, Austria, Lithuania and Czechoslovakia. Our politicians spread false optimism, forecasting a quick victory over the Germans by the Polish-French-British coalition. The Polish people, on the whole, felt intensely patriotic and upbeat. Any form of acquiescence or compromise was out of the question. Men were not unduly worried. They thought of war as inevitable and dangerous but still an interesting interlude. Some were looking forward to it as an escape from the dreary life of daily chores, a nagging wife or an insufferable boss.

Our water carrier Mendel, an elderly Jew, said he was going to volunteer for the army. When the other water carriers (there was a whole guild of them in Horodenka) asked him if he was not afraid

to go to war, he said, "Oy-vey, war schmor. I go to war, kill a few peo ple and return home."

"And if they kill you?"

"Kill me? Why should they? What for? What have I done?"

For our family friend Mr. Krzyzanowski war was to be his salvation. He was so much in debt that it nearly drove him crazy. I still remember his furrowed brow at our card table when he would seek reassurance or at least a nod from his whist partners. "Say, director," he would ask my father, who had been the principal of a teacher's college, "there's bound to be war. There's no other way. Am I not right?"

After all, in Poland it was an axiom that each generation goes to war twice. (Our victorious war against the Bolsheviks had ended only nineteen years before.) Worry was left to mothers, wives, sisters and daughters. It was their job to fend for elders and the little ones while their men were denting their sabres on enemy armour. But meanwhile we youngsters in Horodenka were enjoying what proved to be our last carefree summer. The skies were blue, and the hot Aug ust sun tanned our bodies to the coveted chestnut brown. Our only worry was that something would go awry, and we would miss having a war. And then things began to happen.

"It's for your son."

I recognized the voice of the sergeant who worked in the local Draft Board office across the street. He must have been talking through the open bedroom window to one of my parents.

"Will you sign for it, please? Thank you."

I heard his army boots crunching gravel along the path as he marched back to the garden gate. The latch clicked and he was gone.

That morning I had been reading in bed before breakfast. But now I sprang out of bed and pushed open the door to my parents' bedroom, letting through a gust of the morning breeze. The muslin window curtains billowed in like the sails of a ship scudding into the room. Only my mother was there. She was standing near the open window with one hand clasping the top of her housecoat. In the other hand she held a small sheet of paper. A printed form with a diagonal red stripe.

Seeing me, she tried to hide it behind her back. Then her arm dropped down in a helpless gesture. The paper floated to the carpet. She stood still and stared at me.

"Holy Mother of God! They are taking my child!"

She made a small step forward and stretched her arms as if she wanted to embrace me. I picked up the intriguing paper from the floor and drew back from the range of her pleading arms. Signs of affection embarrassed me. Besides, I did not like being called a child. I glanced at the paper. Below the lines of fine print was my name and in bold type "Call-up to Active Duty. Group C." It was a surprise. I felt honoured. I was only sixteen.

I got dressed in no time. When I went back to my parents' bedroom, mother was still standing at the window motionless, only her lips were moving in inaudible prayer.

"I've got to go, Mum. You know. I've got to report at the Draft Board office."

She said nothing but kept staring at me and nodding her head. I came closer, and as I kissed her on both cheeks, I tasted the salty tears which trickled along the crow's feet around her eyes

It was Thursday, the 24th of August, 1939, when I received my call-up papers. So did the other high-school students who had completed at least the first half of the military training course which normally started in the first year of the lyceum (equivalent of grade eleven). By some quirk the grade eleven class in 1938 had only eight male students, and so we boys from grade ten had been taken to make up the number needed for the course. Because I entered the high school a year earlier than normal, I had completed that half of the military course at sixteen instead of the usual eighteen.

Inside the Draft Board office, Sergeant Gruber greeted me with a short, "You are too early." For a moment I was scared--I thought he was referring to my age. But I was relieved to see that he was pointing at the clock which showed ten to nine. The office opened at nine. A few of my friends appeared. We were all sent to the local depot of Strzelec, a state-sponsored paramilitary organization, to get our uniforms and rifles. I could not find a uniform small enough to fit me.

While I waited for one to be altered for me, I wore my khaki Boy Scout shirt, the long, dark blue trousers from my high-school uniform, a forage cap and a wide army belt.

My first two days "on active duty" I spent riding furiously on my bike all over town delivering messages from the Draft Board to other offices and to individuals--including a love letter in a mauve envelope from Lieutenant Beloshiyev to his fiancée. On the third day, I was detached to the air-spotters unit, which formed part of our countrywide air observation system. Then on the 28th of August I was transferred to a border guards unit near Serafince village beside the Polish-Romanian border, just six kilometres from my home.

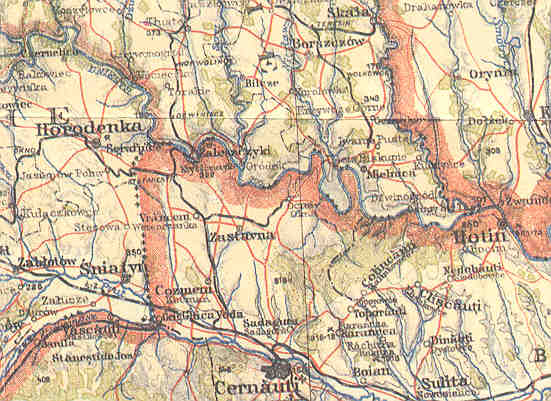

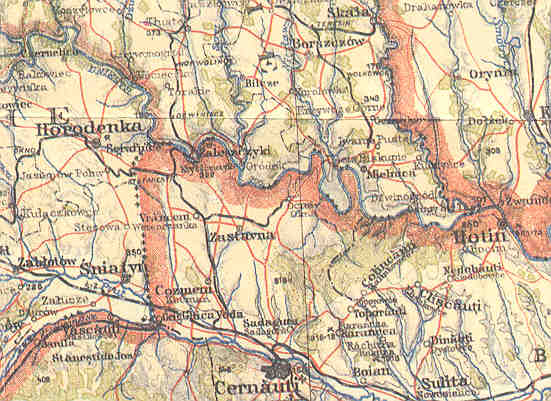

Map of the southeastern corner of Poland as it existed in 1939. On the left: Poland; on the right: the Soviet Union; below: Romania. The map covers an area 60 miles wide. Click for enlargement of the area around Horodenka |

Our post was a white one-story house ringed by tall poplars, which stood out like a green island in the midst of rolling fields still golden with the stubble of harvested wheat. Despite the heat, the post's commandant, Senior Guard Mazur, sat in his office completely buttoned up. He got up when I reported to him and looked me over well, as if bemused by his new charge's childish appearance. Finding nothing else to compliment me on, he said, "You have a fine sounding surname. Now take your things to the big room behind the kitchen. You'll be sleeping there on the floor with the other draftees. Report for duty at 20:00 hours in this office--four hours at the telephone and four hours outside plane spotting."

"Plane spotting at night?"

"Yep. The buggers fly at night too. Dismissed!"

Sleeping on the floor was not too bad because the pine floor was scrubbed with lye every few days. However, the stench of human bodies in our sleeping quarters was so thick that, in Mazur's words, "You could suspend an axe in mid-air."

Our duties were undemanding and tedious. To keep us on our toes we had to send practice reports marked "Dummy" four times a day. Most of the draftees were from Polish farms in the nearby villages and were terrified of the telephone, never having used one before.

When off duty, I'd often ride my bike home for a meal, a change of clothes or just to get a good night's sleep in my own bed. It was after one of these nights at home when, on the morning of September 1st, I heard our national anthem being played on the radio before the eight o'clock news. That was unusual, and my heart pounded as I listened to the anthem. Then the speaker announced the President of Poland, Ignacy Moscicki. After a few clicks and squeaks came the voice of our leader.

"In the early hours of today, the eternal foe of the Polish Republic forced its way through our borders, a fact I state in the face of God and history. I declare Poland in the state of war." Then he listed the cities which had been bombed and proceeded with patriotic exhortations. I did not listen to the end. I leapt from my bed, ran to the kitchen and spun Pyotrusia, our kitchen maid, around. That wasn't easy for she was a strapping lass.

"Pyotrusia! The war has started! Yippee! No more school! We go to war!"

She thought it was one of my pranks.

"Don't say things like that. You may say it in an evil hour and cause it to happen."

She crossed herself. I told her I was not joking. I had heard it on the radio. When she realized that I was telling the truth, she opened wide her blue eyes and began to cry. Her strong jaw trembled as she tried to suppress sobs, while she continued to prepare breakfast. Then she said, "My brother!" and I remembered that she told us he had received his call-up papers the day before. Within minutes the entire house was awake. Mother came running in and embraced Pyotrusia. They both stood there crying and hugging each other. From the far room across the corridor my sisters, still in bed, were shouting, "What happened?! What's going on?!"

Father put the brouhaha to good use. He got dressed without attracting anybody's attention, skipped his morning coffee, and when Mother went looking for him on the front porch, she just managed to catch a glimpse of him as he was turning the corner at the end of the street carrying his fishing rods and tackle box.

For weeks we had expected the war to start any day. But it jolted everybody when it came, even though the general mobilization had been announced the day before. Throngs of called-up reservists, almost all of them Ukrainians, were already arriving from the neighbouring villages. I saw them being led first to the schoolyard. There they were seated at trestle tables laden with loaves of fresh bread, bottles of beer and coils of steaming fat sausages with garlic and marjoram, a gift from the wealthy, fat butcher Ludwik Tomkiewicz, who was also our mayor. After they ate their fill, it was time to go to the railway station. They would form in columns eight abreast, arm in arm, taking the entire width of the street so that nobody could pass them. This was to show their contempt for the lesser breed, the civilians. And they sang in harmony as they marched, making up new--and irreverent--lyrics that showed scant respect for military life.

It seemed that with the outbreak of war, a lot of men likely to be called up, and even some of those who were infirm or too old for the army adopted a semblance of military bearing. With their heads high and chests puffed up, they would strut briskly, confidence beaming from their clean-shaven faces. Women were less affected by martial feelings. My mother busied herself with traditional preparations taught to her by her mother and grandmother. She began buying in bulk and storing flour, sugar, tea, salt and jars of lard. And in the darkness of the night, she and my father buried in the back garden some of our silverware and other valuables wrapped in grease-soaked linen.

Twice a day at nine o'clock in the morning and in the evening, people would gather around their radios to listen to the news. Those who did not have a radio would go to neighbours who did. Mr. Ciolek, the tailor who lived next door, and his subtenant Mr. Piorewicz came every evening just before nine and sat in front of our Telefunken radio set, gazing at the green tuning light which glared back at them like the eye of a basilisk.

One by one Polish radio stations were knocked out by German bombs, and after two weeks all of them except the subsidiary Warsaw Two radio station went off the air. What news we did get was anything but good. The Polish Army was being cut apart by the steel of the German panzer division tanks. The German Luftwaffe ruled the sky, bombing and strafing towns, railway stations, military and nonmilitary targets, and the civilian population, which took to the road by the hundreds of thousands trying to escape the Nazis. That was well nigh impossible because the German armies were invading Poland simultaneously from the north, west and south.

Great Britain and France declared war on Germany but it was a token gesture and did nothing to relieve German pressure on Poland. The unusually hot and sunny September favoured the advance of the Germans. We prayed for the fall rains that would have turned our dirt roads into mire and stemmed the onrush of the German mechanized divisions. Alas, the rains came too late.

When several of my high-school friends and I received our first army pay we decided to celebrate it together at Spiegel's restaurant. For the first time I put on my army tunic, altered at last by the tailor to fit my boyish frame. I was so proud of it I wouldn't think of taking it off although it was a scorchingly hot day. We slouched at the central table and pushed our chairs away from it, so we could stretch our legs and show off our heavy army boots. We offered each other cigarettes. Each one of us had bought a different brand. The owner himself came to serve us. Some ordered vodka, some beer. I opted for Gdanska Zlotowka (Danzig Goldwater), a liqueur with tiny flecks of gold foil floating in it. Maciek Konopka, who was a bit older than the rest of us, proposed visiting Stefa, one of the town's three prostitutes. But most of us felt uneasy about his idea. We got out of it by saying that it was too early in the day even to ponder such matters, which bloom better under cover of darkness and discretion.

The speed of the German invaders was unbelievable. Refugees from western and central Poland started appearing in Horodenka. Rumours abounded about water wells poisoned by "fifth column" saboteurs, about poisonous chocolates and candies dropped by German planes, and about regiments of Polish-speaking German soldiers dressed in Polish uniforms. The refugees were talking about total disarray and the near collapse of the Polish Army. We did not want to believe them. But then my Aunt Jania arrived from Modlin in central Poland with her two small children after a nightmarish journey on bombed trains. She was followed by more of my mother's relatives, including my Uncle Tadeusz with his wife and small daughter. Their stories confirmed our worst fears. The war was already lost.

This was brought home to us twice in mid-September when droning German squadrons flew high overhead and bombed Horodenka. This caused panic among the townsfolk but little damage. One batch of bombs fell in fish-breeding ponds. Most of the others exploded in gardens and orchards, leaving puny holes that looked to me more like pits dug to store potatoes for winter.

But much worse was to follow. On the 17th of September, a guard who had just finished his border patrol came to see our commandant. He said the Romanian border guards told him that the Soviets had declared war on Poland. We were all stunned by this news. Nobody had ever admitted such a possibility, although the improbable Ribbentrop-Molotov friendship pact between the Nazis and Soviets signed only a few weeks before made every Pole feel uneasy. The news was confirmed a few hours later on the radio.

That day the one-way traffic on the road leading to Romania was heavy with a procession of trucks, cars, buses, artillery pieces, horse-drawn carts, ambulances and even fire engines. The soldiers and civilians on them were grey-faced, exhausted after two and half weeks of retreating under bombs. They were leaving their homeland for some other country where-they were told--their army would be recreated to fight the Germans and come back victorious. How long that would take nobody knew. Perhaps it was just as well they didn't.

In the afternoon a rather old-fashioned plane flew by. A biplane. Its engine sounded like a slow motorcycle. As it was passing our border post, it let out a burst of fire from its machine gun. The bullets hit the ground near the main entrance. The plane flew away but then it made a circle and started coming back straight at us. I started running toward the open field to be as far as possible from the house. I ran fast, stumbling and falling on the flat ground covered with wheat stubble. There wasn't a ditch in sight where I could take cover. I could hear the plane coming closer, and I felt as helpless as a rabbit being pursued by a hawk. I hit the dirt and when I looked up, the plane, which was flying very low, took such a sharp turn I could see the goggled face of the machine-gunner. The plane looked like the RB Soviet reconnaissance plane that I had seen on aircraft identification charts at the air-spotters unit. As it made another turn I noticed the red stars painted on its wings. There was no more guessing. It was a Soviet plane. I picked myself up and returned to our post feeling rather sheepish. But it seemed that nobody had noticed my panicky dash for escape.

Later that afternoon, Commandant Mazur gathered all his subordinates in his office. He told us that he and the other border guards were going to Romania in half an hour, after they had bid farewell to their families. The rest of us could either follow them or go home. Then he turned to me: "You go home. At least for the time being. You are young and the Bolsheviks may leave you alone. If things turn bad, you know the border and you can cross it any time."

Before I left, I saw the guards return and squeeze into a two-horse cart, their rifles upright between their knees, their belongings crammed around them. For the last time, they kissed their wives and patted the heads of their children. "Don't worry. Wait for us. We'll be back before the storks return."

I biked home to find my father and uncles playing cards. Father was a bit annoyed that they were not paying proper attention to the game but discussing the day's events instead. They said the Soviet army was already on the far shore of the wide Dniester River less than twenty kilometres away. But the retreating Polish troops had blown up the only bridge in the region, so the Russians were not expected to enter Horodenka before morning.

My Uncle Tadeusz, although a judge and a sensible, intelligent man, had yielded to years of Soviet propaganda. "You'll see for yourself what communism did for Russia," he declared. "Their standard of living surpasses that of Switzerland or America. There are no prisons in the Soviet Union because they've eliminated crime. And there's no unemployment. As for food, Russia was never short of it. In 1915, we all saw the mountains of flour, bacon, sugar and tea that came after the tsarist armies."

My father was not impressed. "Relax, Tadeusz. Stop waving your arms about. We can see your cards. You'll be the first unemployed when they come here. With crime eliminated, there'll be no job for you."

Next morning I left the house quietly while my family and my relatives were still asleep. The sound of engines and feeble cheers led me to the centre of town. There were only a few people in the streets. The stores were closed and the windows shuttered. Some peasants, hoping for loot, carried empty gunny sacks over their shoulders. About a hundred men stood on the sidewalks along the street through the main square. Many were members of the newly formed Communist militia, still in civilian clothes but with red armbands. The militia, or properly the People's Militia, was the name for the new policemen, the civil force of the communist state. Their job was to maintain public order and to serve the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. Our old police force was being disbanded. Its members were arrested, and the word "policeman" became synonymous with "enemy of the socialist system and torturer of the working classes."

Those in the streets welcoming the Red Army were waving their arms, cheering, throwing flowers and blowing kisses at the Soviet tanks as they rolled by. The tanks were small by today's standards, but they seemed huge to me then. Their crews in black leather helmets looked sullen and were not responding to the cheers of the onlookers. A red banner was stretched across the street with the inscription, "Khay zhive Chervena Armia!" the Ukrainian equivalent of "Long live the Red Army!" I noticed somebody had made a mistake by writing khay instead of nay. But I learned much later it was no mistake. The word khay was standard usage in the Soviet Ukraine. The "spontaneous" banner had been made in the Soviet Union and brought by the invading troops.

Gradually the crowd on the main square grew bigger as more and more people left their houses and came to gawk at the Soviets. After the tanks came columns of trucks packed with soldiers standing up. Then came heavy artillery with guns being pulled by tractors. They lumbered by at the pace of a turtle. The next column of trucks created quite a stir among the villagers, who were now coming in droves to see the "Russkies." Inside each of the canvas-covered trucks were two horses. The peasants were wondering why the horses were being driven instead of ridden. Then, seeing that the nags were in such poor shape, unkempt and with their ribs showing, they concluded that by driving them in trucks you could save on fodder. The cavalry, which appeared later near our house, had better-looking mounts. The old-timers noticed immediately that their cavalry sabres were from tsarist times, but the double-headed imperial eagles had been filed off the brass hilts.

In the afternoon, a few trucks and a bus loaded with Polish airmen and soldiers, who didn't know that Horodenka was already in Soviet hands, tried to drive through the town to the Romanian border. They got trapped by the Soviet tanks and taken prisoners. The Soviets locked them up in the girls' primary school near our house, which they quickly converted into a prison.

The behaviour of the Soviet troops astonished the people of Horodenka. There was no stealing, no raping. Even swearing was rare. The soldiers insisted on paying for everything they took and never haggled about the price when they were buying something. And buy they did. By declaring the value of the ruble to be on par with the zloty the Soviets made their soldiers wealthy overnight. In Russia they had plenty of rubles, but there was precious little to buy in the state-run stores and the prices on their so-called free market were exorbitant. But here the prices seemed to them ridiculously low and the sight of stores loaded with merchandise unheard-of in Russia made them giddy. They were buying everything. With the exception of our tobacco and cigarettes, which they thought too weak for their taste, I cannot think of one thing they wouldn't buy.

They would enter any house they fancied, seat themselves at the kitchen or living room table and stay there just looking around, peeking into other rooms, smoking incessantly and trying to engage their hosts in primitive small talk across the language barrier. They would never admit to being ignorant of anything. Any attempt to explain something to them would be quashed by a vigorous, "My znaem, my znaem." We know, we know. When caught looking with incomprehension or noticeable interest at some object they would smile condescendingly and say "There's plenty of that stuff in the Soviet Union." That was difficult to reconcile with their insatiable demand for watches, razors, flashlights, fountain pens, cigarette lighters, pen-knives and haberdashery.

People living near the boys' school, which the Soviet troops had commandeered for barracks, were quick to notice that the soldiers had no underwear. They wore their army trousers and tunics next to their skin. Other things about them also struck us as odd. They washed themselves without soap, lived on hot water, bread and thick soup, and rolled their cigarettes in pieces of newspaper instead of cigarette paper.

Our stores stayed open, but the shelves in them were emptying fast. Now food was getting scarce. Butter and lard had disappeared, and we ate our bread with thin slices of beef fat instead. We sweetened our weak tea with saccharin and washed ourselves with grey soap which Father cooked up from tallow and ashes. The older generation took it in stride. They had lived through it before. What was new to all of us was the quantity of Communist newspapers, propaganda books and posters showered on the public at little or no cost to the consumer. And now only Soviet films were being shown at the cinemas.

We couldn't get over the shock of Poland's defeat. It was beyond our comprehension that a country could collapse in less than a month. We laid the blame for it on our government, our politicians, our generals. The feeling of shame burned deep inside us. Only German conquests yet to come were to show that our debacle was not unique. Within a year the German armies were to roll over Denmark without a shot being fired. Norway showed only a token resistance. Then the combined forces of Belgium, Holland, France and Great Britain were to be swept away by a blitzkrieg that lasted only forty days. In less than three weeks, the Soviet Union would lose to the Germans an area four times larger than Poland did in 1939.

Our defeat spurred the small Polish community in Horodenka to tighten its bonds. Of the 17,000 inhabitants in our town less than 10 percent were ethnic Poles. The rest were Ukrainians and Jews. From the first day of the Soviet occupation small groups sprouted up to help other Poles in need. The airmen and soldiers imprisoned in the girls' school were going hungry. The Soviets would not or could not provide any food for them. Within a day the wives, the sisters and the daughters of Polish families scrounged food from their larders and gardens, pooled their resources and set up rudimentary field kitchens in our garden. Soon unidentifiable soup was perking in the copper cauldrons and slices of bread were stacked on blankets spread on the ground. But it took hours of haggling and pleading before the guards would agree to distribute these among the prisoners. Meanwhile, young boys barely over ten years old brought baskets and handcarts full of apples and tomatoes and were pitching them to the prisoners standing at open windows. Chased by the guards, the youngsters would retreat behind the fences only to reappear in a few minutes and resume their charitable bombardment. Some of the apples were thrown back by the prisoners with messages scribbled on scraps of paper inside them. The messages were addressed to families and friends living all over Poland. Not one of them was ignored, and some people were assigned the task of finding a way to deliver them.

With the defeat of Poland, my army career had ended, and I had to go back to school. The subjects of science, maths and languages remained unchanged for the time being. Other subjects had to wait for new politically correct programs and handbooks. Trying to carry on with our lives as before, we laughed at the uncouth Ivans and their attempts to graft their "communist paradise" on our soil. Then the news of arrests and disappearances of harmless individuals began to strike home.

One day our geography teacher, Jan Jurkow, did not show up for his morning lecture. During the first recess the corridor was abuzz with news about him. In the middle of the night Jurkow was taken from his home by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, assisted by the local militia who told his wife and nine-year-old daughter not to worry as he would be returned home in an hour. This was the last time they saw him. He was arrested for being the editor of the local biweekly newspaper Horodenka News and was destined to survive the war but never return home.

More arrests followed. Eventually they became a daily occurrence. We could see no pattern in the selection of people taken from their homes in the middle of the night--lawyers, teachers, factory workers, small farmers with half an acre of land and one mangy cow or two goats, young people and ninety-year-old pensioners. They were mainly Poles but with a sprinkling of Ukrainians and Jews. People disappearing from our midst, however, had not necessarily been arrested and imprisoned by the Soviets. Some of them had escaped to Romania or to the German-occupied part of Poland where they thought they might be safer.

Those who felt vulnerable (and that included my father) started wrapping up clothing and food in a bundle each evening in order to be ready in case they heard a quiet knock on the door during the night and the order "Otkroitie dveri!" Open the door! The dog collar of Soviet rule was being replaced by a noose of terror. And it was getting tighter and tighter.

For centuries Poles kept alive a tradition of forming clandestine organizations to fight whoever occupied our land. We had a lot of practice at it. There was no Polish state from the late 1700s until 1918. During those years our land was divided among Germans, Russians and Austrians. And now the resolve to organize a resistance group sprang to the minds of thousands of Poles who were watching their country overrun by Germans and Soviets. We were born with conspiracy in our blood.

So I was not surprised when, barely two weeks after the Soviets entered Horodenka, my friend Boguslaw Nowohonski asked me to come to a secret meeting at his home. He was only one year older than me but far more mature. There were only five of us besides him and we were told to come after dusk at irregular intervals. I was the last one to arrive. On two small tables were two chessboards with chessmen arranged as if in mid-game. "That's in case somebody comes and asks what we are doing here. We play chess." Nowohonski told us that we were to form a cell in an already existing secret underground army. For the time being he would not tell us the name of that organization. Each cell had five members, and only one of them would know the name of a member from another group. And we wouldn't know which of us was the chosen one. Our tasks would come from above. Until then, we would simply observe and report anything that might be of interest to our superiors. Then he lit two candles in front of a small bronze crucifix and asked us to place the tip of our hands on it and swear that we would never divulge to any non-member the secrets of our organization.

Meanwhile the local militia was trying to outdo the NKVD in their attempts to eradicate the "counter-revolutionary element" in Horodenka. They compiled lists of people who had been active in such pre-war "reactionary" organizations as the Red Cross, Voluntary Fire Brigade, Boy Scouts, and Sokol Gymnast Association. All of them were considered suspect, and one by one they were being arrested. Houses were searched for no apparent reason. Passersby were stopped and searched. At times innocent persons walking along a street and talking to each other would be pounced upon by militiamen or the secret police agents, separated, and then asked, "What were you discussing?" If their answers did not tally, they would be arrested, and they could expect unpleasant and lengthy interrogations. When I was with my friends in a public place and our conversation was likely to slide into a dicey topic, we would agree beforehand on a subject (usually football or bridge) that would satisfy an inquisitive gumshoe.

The wartime atmosphere and press of relatives loosened our home routine. Also Pyotrusia had left us, believing she'd find better work and pay under the new regime. (She didn't.) Casual help-yourself and grab-what-you-can replaced formal sit-down dinners and suppers. Nobody asked me to explain when I came home late or missed a day at school. I began spending more time in the company of girls from our high school.

Two witty and spunky sisters, Dzidka and Krysia Rutkowski, became close friends of mine. Their father, our reeve, had been arrested by the Soviets. When they were turned out of the reeve's official residence, they tossed a box of Polish passport blanks onto a pile of rubbish. Later, Krysia, the younger and prettier sister, carried them out under the noses of the militia guards. She also brought out the official rubber stamps buried in the bottom of a flower pot.

They moved with their mother into a large but dingy room offered by a friend, yet they carried on as charming and gracious hosts to many visitors including me. We played auction bridge on suitcases stacked between their two beds and danced to gramophone records on a small patch of floor between two tall wardrobes. Their mother was now supplying members of the underground with passports. Krysia presented me with one too, "just in case."

Day by day I got more enmeshed in the risky business of helping those who believed that their place was in the ranks of the Polish Army in France. I was meeting them at the railway station, taking them from there to safe houses through back alleys and garden paths, and delivering messages and parcels.

At the same time, unbeknownst to me, my sister Maria was doing the same things for another group which was in the business of smuggling volunteers across the border. Maria has always been the outgoing and athletic one with more concern for others than herself. She was to go on to be a doctor. My father took some risks too. One moonless and rainy night he opened the back door of the town hall with a skeleton key and, helped by two Boy Scouts, carried out from the storage room our troop's standard, tents and camping equipment without waking a sleeping militiaman. They had to make several trips to carry out all that heavy gear and tuck it away under the garret rafters of our old high-school building so that it wouldn't fall into the hands of the militia.

Two of those who took the oath of secrecy with me at Nowohonski's house called on me one evening. We talked for a while about nothing in particular. They kept cracking jokes, but their joviality seemed to me a bit overdone. They were smoking incessantly. Before long they let the cat out of the bag: they were going across the border to Romania that night. They couldn't contact Nowohonski, who was out of town, and so they asked me to break this news to him.

Next morning, when they didn't show up at school, everybody guessed what had happened. I decided that I was going to follow them to Romania very soon.

* * *

In October, the Soviets and the Germans reached an agreement about repatriating people who had escaped from the Germans occupying central and western Poland and found themselves in the territories annexed by the Soviet Union. My aunts and uncles started trickling back to where they came from. News about the departure of my uncles, aunts and cousins reached the local militia, and in no time, a red-haired creature with a star on his cloth cap banged at our front door. As soon as we let him in he started going from room to room, looking around. He carried a rifle slung under his arm the way hunters carry their shotguns. He wasn't used to carrying one and it kept banging against furniture and doors. His gibberish, which purported to be Russian, was a mixture of Yiddish, Polish and Ukrainian, garnished with a few Russian words. But his message was clear. We had too much free space in our house and father's study would be requisitioned for two Soviet officers.

The Soviets always billeted their men at least two to a room, not to save on space but as a way of tightening security. Roommates could see to it that neither one became friendly with people of unproven loyalty.

Our two new tenants were a pleasant surprise: a colonel and a major. Both were polite, well mannered, quiet, and almost timid. They tried to make as little trouble for us as possible. They asked Pyotrusia --who had come back to us by then--not to bring them hot water for their morning wash and shaving. Cold water was good enough for them. And they were aghast in the morning when they found their shoes shined by her.

For a long time they would not accept mother's invitation to have tea with us in the living room. When they finally said "Yes" they brought with them a cup of crushed sugarloaf and a small packet of tea from Georgia. They stayed for twenty minutes or so. The conversation was limited to repeating spasibo (thank you) and, "What do you call that in Russian? In Polish?" while pointing at different objects. But as their visits became more frequent everybody became increasingly adventurous and talkative, In the course of time the Russians lost their initial shyness and started dropping in on their own for chashku chayu (a cup of tea).

Of the two officers, the colonel was more affable. He had some smatterings of German, which we understood, and called Maria "mein Kaetzchen" (my kitten). Once he brought a box of pastries from Bohrer's caf? One day while listening to Maria playing the piano, he came closer and pointed out the notes of some chord that she con tinued to hit wrong. He even corrected the position of her hand. Asked if he could play piano, he smiled broadly and with one finger picked out the Russian equivalent of "Chopsticks." Then in a nice baritone he sang a little tune. It was a children's song about a puffed up birdie, a siskin (chizhik in Russian). He sang it again and again until Maria learned the tune and the words by heart. We started calling the colonel Chizhik, and he liked that.

His roommate, the major, was a withdrawn character who seldom smiled. We could tell by the way he kept looking at my older sister Henia that he was smitten by her. But he was tongue-tied around her. To make up for his conversational shortcomings, he would read aloud to her long political articles from the Russian newspapers Pravda and Izvestia and from books by Lenin and Stalin. Henia-- whose heart was already taken by another--not only put up with it, she even created the impression of being interested in what he read.

One evening, Chizhik came for tea without his pal, the major. He was in an excellent mood that evening, cracking jokes and paying compliments to my mother and sisters. He asked Maria and Mother to play the piano. Maria went through her short repertoire, good-naturedly laughing at her own mistakes. Mother followed her with bits and pieces of Czerny and Schumann, then ventured into Tchaikovsky's "Months" and "Troika." As usual she stumbled at the fast tempo of the finale of "Troika." She smiled and glanced at Chizhik. Turning her hands over, she looked at her spread fingers as if she was blaming them for letting her down. She got up and with a sweeping gesture invited Chizhik to take her place at the piano. A roguish grin broke out on his face as he accepted her challenge. We expected a joke. With a flourish he swept up the tails of an imaginary dress coat and sat down to play.

He took up the "Troika" where mother had left it, gliding with ease through the fast notes of the jingling sleigh bells. He went through another piece of Tchaikovsky's music that Mother had played that evening and then, while improvising with his left hand, leafed with his right through a stack of sheet music, pulling out those he was going to play. I don't know how long he performed, but the glasses of tea brought in by Pyotrusia grew cold.

Chizhik finished his impromptu concert with a mighty chord, He stretched, leaned himself back and rested his head on his hands which he clasped at the back of his neck. His eyes wandered from a gold-framed seascape by Wygrzywalski that hung on our wall to a small aquarelle by Kossak. He then gazed for a while at the credenza adorned with Bohemian crystal and at some family silver arranged on the shelves of the large cupboard. He closed his eyes and sighed. "My God! We used to live like this."

Then he jumped to his feet in a military fashion, went to the door to the corridor, opened it and without turning around said, "Spokoinoi nochi!" Good night!

After the unscheduled piano recital, Chizhik's visits became rare. He would drop in only for a few minutes and as often as not decline the offer of a cup of tea. It is hard to believe that we never learned the surnames or even the first names of our Soviet officer tenants. But they never told us their names and we knew better than to ask.

There were rumours among the members of the clandestine resistance that members of our secret organization in Horodenka, including me, were being targeted for arrest. Deep at heart I believed that I was too young to be a serious suspect on the files of the militia or the NKVD. But I was scared. I went to Lusia Klonowska, a friend of my sister Maria, who was said to know much about the situation in Horodenka. "All these stories," she said, "are pure gossip. Nobody knows anything for sure. And people tend to exaggerate. But if you feel that you are in danger, well then, cross the border. A lot of your friends are there so you won't be alone."

When I returned home from Lusia's, I found the house full of strangers--five men and a woman. "They are from Lwow," explained Maria, "and they are going to France via Romania. Somebody directed them to our house."

"I'll go with them."

"You'll what?!"

I just nodded and went into the dining room where my parents chatted with some of the unexpected visitors. Father and Mother were relieved to see me. They had not seen me for three days. They looked at my flushed face but remained silent as if expecting me to say something.

"I'm going with them!" I blurted out, turning to look at the strangers. "Tonight, tomorrow or whenever they go!"

At the beginning my parents wouldn't even talk about it. But I kept trying to persuade them to let me go. I gave them dozens of reasons why I could not stay in Horodenka and why I should go to Romania. Mother wanted to say something, but I wouldn't let her interrupt my torrent of arguments. Father sat with his head down, turning his signet ring around his finger. When I stopped my tirade for a moment, one of the visitors, a tall, dark man with a big nose and horn-rimmed glasses, who was a bit older than the others, turned to my parents.

"We probably could arrange for him to continue his high-school studies in France. Professor Kot, now a minister with the Polish Government in Paris, is our personal friend."

That was a breakthrough and I sensed victory--though limited. High school, my foot! I thought. The moment I'm there, nobody's going to stop me from joining the army.

Next day Monday December 11, 1939, was a busy one. Morning mass, confession and communion. A visit to a photographer, so my mother would have a recent picture of her boy. Selecting photographs and souvenirs to take with me. Scratching out and changing the date of birth in the passport Krysia gave me. I wanted to make myself one year older. To volunteer for the army one had to be at least seventeen.

I was itching to tell some of my friends that I was leaving, but no one more than Krysia. In the evening I ran to her place. I never realized how fond I was of her until the day of parting. I was out of breath when I got there. Her mother and her sister were outside in the shed chopping wood for the stove.

"Krysia's in. We'll join you in a moment."

She was standing at the window. She turned around as she heard me coming in. I saw her silhouette against the salmon-coloured sky of the sunset.

I said, "Krystyna!" It sounded more dramatic than the diminutive Krysia. "I am leaving tomorrow for Romania. From there on to France to join the army." I hoped it sounded as good to her as, "My regiment leaves at dawn."

With a mighty hug and a kiss she pre-empted my timid attempt to embrace her. We went into a prolonged clinch. With almost imperceptible steps I steered her in the direction of the part of the floor screened by the two tall wardrobes. Once there she pushed me away a little and began undoing the buttons of her blouse. I thought of an old oil painting of a romantic farewell scene that I often looked at in my grandmother's house. In it, a young woman was offering her rosy breasts for kissing to her swain who was about to depart for war. Krysia was giving me the same kind of send-off, one I wouldn't have dared to dream about.

We both spoke the last goodbye at the same time. Afterwards I realized that the scene in that old oil painting was not an artist's romantic vision but a living tradition.

|