| Book chapters |

A Polish Christmas Eve:

Traditions and Recipes, Decorations and Song

By Rev. Czeslaw Michal Krysa

CWB Press

Copyright, 1998 CWB Press.

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0-966-1099-0-202569-5

Chapter Four

|

VIGIL SUPPER FOLK ART

|

|

What is the difference between a cookie and a birthday cake; a wine cooler and champagne; a package of blown glass ornaments and grandma's Christmas angel; costume jewelry and an engagement ring? Part of the difference lies in the distinction between something and someone. While we can have many cookies or coolers, purchase different ornaments or costume jewelry, birthday cakes come once a year, champagne on special occasions, heirlooms once in a lifetime, and engagement rings once in a loving relationship. Above all, birthday cakes, champagne, and heirlooms may express how we love and cherish each other; there is more to them than flour, a beverage, or precious metal.

There are other differences as well. While one might munch on a cookie or sip a wine cooler, birthday cakes come with candles, messages written in frosting, wishes, and a person who cuts and shares the pieces. Toasts accompany the sharing of champagne, along with the raising and clinking of glasses. That's not the way we down a refreshing cooler on a hot summer day. Heirlooms are safely packed and stored, often displayed in distinctive cabinets or on special anniversaries. Engagement rings are usually not worn while washing dishes. Mementos that connect us with someone are treated with exceptional care and respect.

Family heirlooms deserve special respect, like a recipe handed down from grandma or even a certain item once used by a beloved member of the family who is deceased. A cherished keepsake or family custom evokes strong emotional bonds, bringing to mind a person or event. All this is a sign that nothing can separate us from love; remembering is one of the greatest expressions of love. In the words of St. Paul: neither tribulation, illness, calamity, tragedy or even death itself can separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus (Romans 8:3-9). The love of those who shared our life can never end. It continues to live on in the hearts of people who don't forget.

There is a major difference between supper, a meal served on any day of the year and the one served on Christmas Eve. The Vigil Supper profoundly connects us with significant others by means of a memory much deeper than nostalgia. The Vigil Supper's customs, beliefs, folk art, and recipes all elicit an intense awareness of presence. Its symbols and customs join participants to an ancient Gospel heritage originating with two young parents searching for a place to stay in an overcrowded town, the only vacancy they found being a cattle stall.

The Vigil Supper folk art described in the following pages is more akin to birthday cakes, champagne, and heirlooms than to a snack, ornaments, and costume jewelry, because it connects us with someone, namely, those who passed this tradition on to us as a treasured heritage. In this way, it differs from store bought ornaments or Christmas toys. It expresses relationships; it verbalizes hopes; it re-presents those who are absent, evoking a rich heritage.

The symbolic nature of this folk art expresses and captures our deepest longings and aspirations. It differs from purchased decorations because it is handmade, or rather heart made, representing an unbroken bond throughout the centuries uniting numerous individuals and families of kindred heritage. Ordinary straw, paper, wafers, and glue wedded with human imagination produce remarkable handiwork. The Vigil Supper takes a common evening meal and transforms it into an uncommon celebration of family love and solidarity. Daily routine and drudgery give way to the delight of a timeless festival. The folk art of the Vigil Supper actually remembers our past and hopes for the future because it is related to someone, rather than just something. It unites all participants to the "Child who, laid to rest on Mary's lap, is sleeping." In the Infant Jesus promises of the past have taken flesh; the Gospel brings news of peace and goodwill. The customs, the art, and the menu of the Vigil Supper express the essential difference between cookies and birthday cakes, wine coolers and champagne, costume jewelry and engagement rings, ornaments and heirlooms, namely, the human spirit's creative desire to commemorate the events of God's love and celebrate Bethlehem and pass it on.

|

The Magic of Straw

Grain sheaves are the most ancient ritual adornments of the Vigil Supper celebration. Over a period of time the sheaf evolved into other decorations, such as the dziad, the Vigil cross and star. Straw was an abundant, easily available, and naturally beautiful material used to make decorations for the Vigil Supper. Imagine its golden luster in the dim candle light of the village cottage! As a kind of delicate, golden counterpart to mother-of-pearl, its texture captures and gently reflects beams of light. Folk beliefs endowed straw with the magical properties of grain itself (see "Agriculture, Ancestors...," p. 12). In some regions, straw was strewn on the floor of the cottage under the Vigil Supper table in memory of the stable where Jesus was born. This straw remained under the family table until the Epiphany. It was considered sacrilegious to sweep it outside during the Twelve Days of Christmas for fear that one might sweep the soul of a deceased family member out into the winter cold! In some villages of eastern Poland coins were scattered in the straw lying on the floor. After the Vigil Supper, the children crawled under the table in search of the silver coins amid the golden straw. In other districts children rolled in the straw found on the floor to protect themselves from measles. These customs portray a belief in the magical quality of straw, an extension of the ancient ancestral sheaf. |

General Instructions For Working With Wheat

Wheat used for most of the projects in this book, except sheaves, requires the older varieties of wheat that have long hollow stems. If using locally grown wheat, or wheat from a florist, check by cutting across a stem. Newer varieties of wheat have been bred to have short woody stems to hold up well under heavy wind and rain. The solid stems do not squeeze together to fan out properly to make stars, for example. And, of course, you can only string sections of hollow wheat into garlands and mini-chandeliers.

If you grow wheat, or have permission to pick some, remember to pick it before it is actually harvest ready. After the field has turned golden, but while the heads of wheat are still erect, is the right time. You can judge more accurately by crushing a grain of wheat in your fingers. If the grain exudes a milky substance, it is not yet ready. If the grain crushes into flour, you are too late; the wheat will be brittle and difficult to work with even after prolonged soaking. If the crushed grain has the feel of bread dough, it is just right. Harvest and spread stalks out to dry thoroughly.

Wheat may be purchased in craft supply stores. If there is none on display, you may want to ask because it is frequently removed from the shelves since it is considered an autumn craft material.

Wheat varies greatly in size and thickness of stems and heads. It is, therefore, impossible to give exact number of stems or lengths in directions. Work carefully, using your judgement regarding size and scale of the project as you proceed.

TO CLEAN WHEAT: Remove the leaves from the straw by cutting across each stem just above the first "knuckle" you encounter as you run your hand down the stalk from the head. Look carefully so you don't mistake a bent over leaf for the "knuckle." The leaf sheath will pull off from the straw stem like a paper wrapper from a plastic drinking straw.

TO SOAK: Place in cold water until a stem snaps straight if you bend it all the way back on itself without cracking or breaking. Generally, 1/2 hour is sufficient. Wall paper troughs from the paint store are inexpensive and very handy for this.

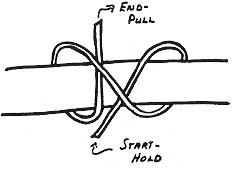

TO TIE: Use a thin strong cord, like button and carpet thread. Nylon thread does not work well because it is stretchy, so thin it cuts your fingers and tends to unknot unless glued. It is important to make the ties very tight because the wheat is swollen with water when you are working with it. If the ties are not firm, your work will look loose and sloppy after it dries. This knot works best: |  |

|

Pull each end of the thread in opposite directions to tighten. You may partially tighten the knot to allow you to arrange the wheat stalks; the knot will not loosen and will help you like an extra set of hands. When the wheat stalks are arranged to your satisfaction, pull the thread ends in opposite directions until the wheat stalks begin to fan out. Finish with a square knot or an ordinary overhand knot.

TO DRY: Allow left over soaked wheat and finished projects to dry thoroughly where there is good air circulation to prevent mildew. Arrange completed project carefully; it will hold the shape in which it dries.

|

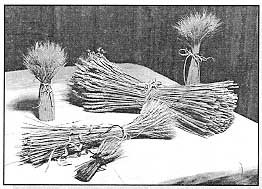

The Sheaf of Grain

The sheaf of grain (snopek) is a central symbol of the Polish Christmas Vigil. It combines hopes for good fortune, bounty, and memories of departed family members with Christ, the "bread of angels" who comes down from heaven. Placed in one or all four corners of the Vigil Supper room, the sheaves are a vivid reminder of the ancient character of this celebration.

|

Photo by Brian Curtis |

|

Photo by Joe Rocco Studios |

Corner Sheaf

You can make the corner sheaf very large so it fills a corner o quite small (see the sheaves in the photo above).

1. See "General Instructions for Working with Wheat" before starting this project.

2. If you want a tall sheaf, do not clean the wheat.

3. Use soaked wheat which enables you to make tight ties without shattering the wheat stems. This allows you to form an attractive sheaf shape.

4. Form the central portion first. Take a bundle of wheat (a good handful or more depending on the size you want the finished product to be). Tie the bundle together an inch or two below the point at which the heads join the stems. Make four or five more tied bundles. Arrange these bundles around the central bundle and tie them all together an inch or two below the previous ties. You should now be able to see your sheaf taking shape. As your sheaf grows in girth, you will need more bundles to encircle it. If it is too large to tie all the surrounding bundles on at once, tie a few bundles on one section at a time. The knot described in "General Instructions for Working with Wheat" will help you immensely in this project. If you are making a very large sheaf you may want to start using twine instead of thread as the sheaf grows.

5. The finished sheaf must dry in the shape you want it to maintain. If you lay it down, it will dry with a flat

side. If you want it round, it is necessary to keep it erect until it is thoroughly dry. Small sheaves may be

placed in a heavy mug or drinking glass; large sheaves could be placed in a wastebasket or propped up.

|

|

|

|