EUGENE M. DYCZKOWSKI

Eugene M. Dyczkowski was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on May 1, 1899. His father, who at the age of 16 had emigrated to American from the Russian occupied area of Poland, studied music at the Philadelphia Conservatory of Music. Later, he became a noted organist at a local church where he met his wife, Pauline, a vocalist in the choir. Eugene was the second of their 11 children. |

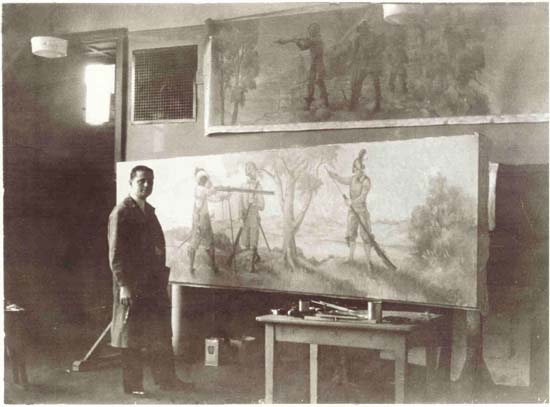

Eugene Dyczkowski painting the Officers Club mural. |

The significance of the M-1 Garand is that in 1939, when Dyczkowski painted the mural, the Garand was new and very “high tech.” Mass production of this rifle had begun in 1937, only two years earlier. Its use in World War II gave American soldiers an advantage in firepower.

Under the WPA Project Dyczkowski also painted two murals at the Burgard Vocational High School, in Buffalo. The panels represent trades and occupations, thus Science, Printing, Aeronautical Engineering, and Automotive Engineering. Dyczkowski also repaired and restored other artist’s paintings at the Old Fort.

From 1936 to 1939 Dyczkowski had the honor to serve as President of the Buffalo Society of Artists. In 1940, disturbed by what he perceived as incompetence on the part of jury selecting works for Western New York exhibits sponsored by the Albright Art Gallery, he entered a deliberately primitive and crude painting. He signed it “Noga Malowane.” The jury, in its desire to have modernism represented, had previously accepted questionable works without due regard to quality or ability. Now, it accepted Dyczkowski’s crude painting, but rejected his professional work. I)yczkowski had succeeded in proving his point and, on April 24, 1940, he wrote a gloating letter to the Buffalo Evening News signing the letter “Noga Malowane.' Little did the jury know that "Nogą Malowane" is Polish for "Foot-painted."

Dyczkowski, a professional artist, teacher and lecturer was a co-founder of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo and served as its first President, holding the office in the years 1945 and 1946. He believed that Americans of Polish ancestry need to conserve and interpret their Polish heritage so that they can take their proper place in American society. By his actions, he contributed greatly by to raising the awareness of the fine arts in Polish American communities nationwide. As a consequence, a Polish Arts Club movement took hold and spread. In centers of Polish American population throughout America, like-minded individuals banded together to form local clubs. Promotion of Polish Culture in the United States took direction and gathered momentum.

In 1947-9, Polish Arts Clubs from all over the United States participated in a conference in Chicago. An outcome of the meeting was a memorandum which established the objectives and procedures for the formation of a National Council. At a second conference, which took place the following year in Detroit, the American Council of Polish Cultural Clubs (ACPCC) was formally inaugurated and Dyczkowski was elected to be its first President. As Co-founder of the Council, he was instrumental in establishing the tenets of the humanitarian philosophies which served as operable and viable guidelines for the Polish Arts Club Movement. He reiterated the importance of the utilization of the highest caliber programs to promote Polish culture.

Dyczkowski was a visionary as well as the leader in this movement. He believed that no matter what project might be undertaken, the value of good taste must be paramount. Culture, he said, "implies good taste and culture is the art of information by education and refining of the moral and intellectual nature." His ideas continue to be embodied in the activities of Polish Arts Clubs nationwide.

In 1949, the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo hosted a National Convention of the ACPCC at Hotel Statler. Eugene Dyczkowski, the chairman of the Convention, was also the driving force behind its success. Through his efforts, a National Exhibition of paintings by Polish American Artists was held at the Albright Art Gallery. He canvassed the entire roster of Polish American painters in the country to gather 74 excellent works. As a gesture of hospitality, local artists from the Polish Arts Club withdrew voluntarily from the competition for prize awards.

In the l950s, Dyczkowski went from being an opponent of modern art to a being a strong proponent of it. He changed his style. He broke with representational painting and began creating works of abstract design. Many a heated discussion took place between him and Gordon B. Washburn, a Director at the Albright Gallery. He now believed that his earlier academic art training had been wasted and that a break with his realistic painting had become necessary in order to apply his new thinking regarding abstract design. A local newspaper headline read, "Artist Wipes Out 30 Years of Work, and Starts Over Again."

Dyczkowski once said: "Elimination of realistic subject matter allows complete freedom of expression in pure design." He looked back at all of his past work and openly declared it to be of “little merit.” It has been said that it took courage for Dyczkowski, years earlier, to give up a successful career as a commercial artist to devote himself entirely to the fine arts. This later resolve to change his style of painting was no less courageous. It was personal honesty at its best. Yet, people who know and treasure Dyczkowski’s realistic works of art would not agree with him that these lack merit. It would seem that his own self-judgment was too severe.

It was at this time that Dyczkowski began to explore all basic facts about composition, line, color and design, which is the essence of a good abstract painting. He not only adapted well to this form of art but also excelled in the non-objective style. For the next 30 years he continued to be actively involved, both nationally and at the local community level, as a painter, lecturer and teacher.

In 1982, Mr. Dyczkowski was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Polish Arts Club in Buffalo. It was there, at the presentation of the award, that I met Mr. Dyczkowski for the first time and then only briefly. In his 80’s, tall of stature, wan, gentle, with a very charming personality, he left a great impression on me. He was not in the best of health and was very apologetic that he had to leave rather quickly.

In 1987, an exhibition of his paintings was held at the Fine Art Gallery in Niagara Falls, New York. On that occasion, the Polish Arts Club, with the endorsement of the full membership, purchased an oil painting by him entitled Bartolomeo It was then presented to the Burchfield-Penny Art Center in Eugene Dyczkowski’s honor. It remains in the Artist’s Polish Heritage Collection at the Center.

Mr. Dyczkowski died in 1987 at the age of 88. His legacy is the enhanced awareness of Polish culture in America and the pride Polish Americans take in its advancement.

The above is the edited text of a presentation made on May 29th, 1999, at the Officers Club in Fort Niagara State Park. The occasion the presentation was the opening of an exhibition of paintings by Eugene M Dyczkowski on the centenary of his birth. The event coincided with the formal opening of the Officers Club as a Museum, the culmination of a two year determined effort by the Club and other public-spirited citizens and groups. The effort to save the building was occasioned by the State having previously agreed to lease it to a private group for redevelopment as a restaurant, the kitchen of which was to have been installed in a room containing Dyczkowski's 90 foot mural Defending Forts. Anna Nowak, the presenter, is herself an artist and one time President of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo.

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |