Images of Women

In Turn-of-the-Century Polish Painting

by Dr. Maria Hussakowska

The topic of my presentation are the images of women that we may recognize as typical in the work of male Polish painters of the turn of the century. In art, the period between 1885 and 1905 is considered as a turning point of European culture, particularly in the visual arts and literature. European art historians call it the period of Modernism. There is no doubt that Polish art of that time - mostly painting - is very close to Romanticism in its special kind of sensibility, more so than in style.A point of departure for my presentation was a dissertation written in the 1970’s by a friend, Małgorzata Reinhardt. Her work dealt with the classical and traditional symbols, themes and subject matter, in a word, iconography, in the painting made of women by the turn of the century male Polish painters. In striving to present the works of these artists, I attempted to do so in a different context, that is, with reference to feminist interpretations of the history of art.

Among the artists active in this period, Jacek Malczewski, who was born in 1854 and died in 1926, holds a special position. That's because he created a specific kind of art, one traditional in form, but also one with a strong literary content, that is, he produced paintings that clearly tell some sort of story. Early on, he declared himself a symbolist and remained so till his death. Much of the symbolism in his paintings has to do with Poland's enslavement and eventual liberation. He was obsessed with that idea. Looking at his paintings, one can guess his religion, his nationality, and even the age in which he lived. Everything - in Malczewski's opinion - ought to speak about his nation and its tragic history. "If I were not a Pole, "he said "I would not be an artist". It was not easy to adopt a modern artistic style with such attitudes.

Malczewski was very fond and much influenced by the Polish romantic poets, Słowacki and Norwid. He absorbed from their poetry both the romantic sensibility and the romantic ideology. This, in fact, was typical of almost the whole of Polish nineteenth century art. Let's have a look at what images of women he created.

Thanatos 1 by Jacek Malczewski, 1898, 49x29" oil on canvas, National Museum, Poznan |

At the Well by Jacek Malczewski, 1909, 34x24" oil on cardboard |

A frequent feature of his paintings, particularly with reference to Poland and its enslavement, are Beauty and Death. These have always been present in European art, but as Mario Praz has written, the Romantics looked upon Beauty and Death as sisters. The two fused in their minds as one entity filled with corruption and melancholy, fatal in its beauty, a beauty of which, the more bitter the taste, the more abundant its enjoyment.

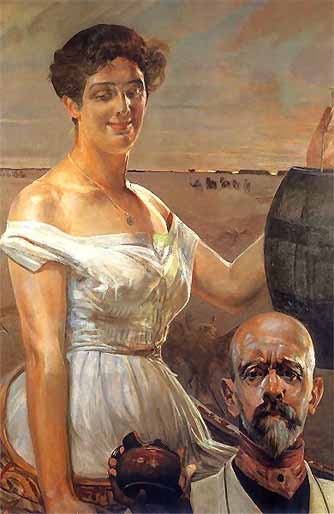

Thanatos, or Death personified, is a key subject of Malczewski's art. Angels of Death appear frequently in his work. Usually, they have the features of Polish women, often of real ones with whom he had affairs. But they are also the object of adoration, as romantic sensibility and the Church demanded. Powerful women appear frequently in the artist's paintings; sometimes they are monsters - half human, half beast - sometimes they are angels, but even the latter mingle beauty and dread. Whether Malczewski's women are Fates, Thanatos or just women-by-the-well, they are always dangerous. They have special powers. We can see it in their strongly built bodies as well as in their knowing smiles. When we look at Thanatos, we get the impression that her body lines are as important to the painting as her costume and other attributes.

How should one interpret the symbolism in his 1898 Thanatos 1 of the beautiful figure of the Death standing in front of the artist's ancestral home, the house where his father died some years before? Is the symbolism purely biographical, or does it involve some Greek myth? or is the artist simply chosen to portray a figure that shows the androgyny so typical of the art of that period.

Woman in a Grove by Jacek Malczewski, 1917, 40x27" oil on cardboard, National Museum, Warsaw |

Malczewski is famous for having painted himself very often. On the one hand, his self-portraits measure the artists' progress along life's road, on the other hand, they allow him to address life's central dilemmas while looking into his own reflection. In his self-portraits, the autobiographical is given universal significance by being linked with mythological figures or episodes. At the same time, the infusion of personal, historical or geographical detail gives the mythical or fantastical compelling immediacy. In some of his self-portraits he is hand-cuffed, another symbol of Poland's bondage.

Looking at the 1909 painting At the Well, yet another self-portrait, we feel that the conflict between the sexes is also very important for the composition. The totally dominant, sculptured body of these women, as always seen from below, emphasizes the differences. Here, he the painter, and something more than just an artist - is almost in despair. She exudes power. For him, as for most romantic artists, she is nature - full of spirit. The work focuses on the perennial conflict between the man and the woman, so typical of nineteenth century art. Man, in the construct of that period, is born without consciousness or knowledge, and, before his spirit returns to God, it is from the woman that he frequently receives an intimation of the infinite.

In the painting, the woman is standing at the well, she is holding a bucket full of water - a symbol of female fertility - water she has drawn from the well. She has given him a wooden cup of water, the water of life which could fill him with wisdom. Her strange smile signals, however, that the effort is useless. The woman, who is shown as the guardian of the well, is looking down on the cup in the artist's hand, but we can see that the cup is broken.

In the Portrait of a Woman in a Grove, another of Malczewski's painting, one dating from 1917, the woman is much more the inscrutable, mysterious beauty. A woman wearing a white dress is standing in a characteristic pose with an almost expressionless face. The time is the Fall of the year and the trees behind her are almost leafless. It is nighttime: the meadows are foggy and white, the river flows calmly by. Everything is silvery in the moonlight. We know how important for the artist were the mysteries of the earth, life and nature. And the Fall season is a symbol of maturity. The painting is easy to interpret, but one ought to note how its composition and harmony recall the style of turn-of-the-century art.

Another artist, in whose paintings we find mysterious beauties, is Józef Mehoffer, born in 1869 (he died in 1946). He was a painter much more in tune with the times than Malczewski. He was influenced by impressionism, but also quite markedly by Whistler and old stained glass windows. His 1903 Strange Garden and his Dreaming Queen are works in which women appeared in fairy tale scenery. He used to paint his beautiful wife and, as Agnieszka Lawniczakowa, an expert on symbolism wrote:

"From the large range of female types - from vampires to nuns - who populated the art of this epoch, Mehoffer chose the haughty, somewhat mysterious lady, and it is thus he portrayed his wife. He became an excellent interpreter of her poses, costumes, gestures, and moods. With her cooperation, he created a painterly chronicle of the life of an elegant women of the fin-de-siecle".

Strange Garden by Józef Mehoffer, 1917, 85x82" oil on canvas, National Museum, Warsaw |

The idyllic, bourgeois paradise appears in many of his pictures. In the 1904 Portrait of the Artist's Wife, she is standing in her salon, the datedness of which contrast with her figure. That same year he also used his wife for his painting, The Head of Medusa, the monster with serpent locks whose gaze turned men to stone - a classic representation of sexual fantasy.

Portrait of the Artist's Wife by Józef Mehoffer, 1904, 58x31" oil on canvas, National Museum, Kraków |

The Head of Medusa by Józef Mehoffer, 1904, 19x14" oil on canvas, National Museum, Kraków |

Polish painters had many different muses, or sources of inspiration. Some derived from their unconsciousness, some from stereotypes they had in their minds. However, during the period we are interested in, the muses were very often folk heroines. This source of inspiration can be seen as deriving from the attitude of the romantics that peasants, close to the soil, were more real, moral, etc.

The nature versus culture debate, which pervaded the ideological mainstream of this period in Polish art, reflected the intrinsic Polish melancholic view of life which rendered suspect the ability of artists to joyfully celebrate the beauties of nature. Artists who were timorous about embracing the "art for art's sake" trend of modernist art, with its departure from the obligatory realism of earlier periods, and some of them became eager to explore art that was socially engaged. The peasant woman in her mythological image, represents at the same time both the strength of the primitive folk and its intrinsic nobility. Her magic force can be identified with the regenerative cycles of nature. That's why the painters painted young girls as well as adult, mature women, and also those women who held a special position in that society - namely those who might be called shamans or witches. The last mentioned were very often portrayed in a grotesque manner.

If we look for the origins of the cultural ambiguities characteristic for Polish art of the period, we need to mention Zorian Dołęga Chodowiecki, who wrote the seminal work for the Polish romantic artist, a book entitled The Slays in the pre-Christian Era. In it he expounded the importance for our heritage of the conflict between the official, western-oriented mainstream culture which had its beginnings with the Christianization of Poland - and the folk culture, which had persisted in its purest form in the Polish peasant's hut.

Painters and, above all, poets and writers of the period we are discussing, readily accepted the idea of culture's duality. The new knowledge of folk culture, derived from the disciplines of ethnology and ethnography, which established themselves at the universities at around this time, probably helped make this acceptance much easier. The highlands to the south of Kraków became the focus of particular attention, for there the folk culture, because of its relative inaccessibility, had remained most vibrant. Writers such Tetmajer, Reymont, Kasprowicz, Rydel, Orkan - who was himself a highlander - built up a new image of the Polish peasant as one who played a special role and belonged to a group with real political power. They very often chose highlanders as the real heirs of the prehistoric Slavs. This artistic glorification had a positive outcome, the creation of the Zakopane style, so-called after a town at the foot of the Tatra mountains, now Poland's best known resort. The creation of the style was the concept of Stanisław Witkiewicz, art theoretician, writer, critic, architect - in short - a renaissance man. His concept of a new, intrinsically Polish national style which would unify architecture in the whole of Poland's ancient territory was quite strange, particularly since the style required the structures to be made of wood. On the other hand, when one looks at the villas he designed, their beauty is obvious. It is also worth noting that his stylistic influence continues to be evident in the second homes that people currently erect in the Kraków area.

What is the image of the peasantry projected in the paintings of this period? Of the painters who dreamt of restoring Polish culture from its folk roots the best known was Włodzimierz Tetmajer. His fascinations with folklore went so far that he married a real peasant woman and spent the rest of his life in Bronowice, a small village near Kraków. He is a hero of one of Poland's most popular plays, Wyspiański's 1901 Wedding. You may have seen the movie version made by Wajda.

Tetmajer's escape from the mainstream of civilization - not so real after all, since Bronowice was but 10 miles from Kraków - was typical for the times. Such well known artists as Tolstoy and Gauguin chose to do the same and to put greater distances between themselves and civilization.

Living in Bronowice didn't diminish Tetmajer's enthusiasm; over and over again he painted the multicolored, cheerful, sunny Polish village. People always wear holiday clothes and the women become much like dolls themselves. When he painted them participating in the harvest, they continue to look like dolls, not like people engaged in hard work. Embellishing the realities of peasant life, he wanted to recreate the myth of a happy land. But what he really created was a prototype for what became the stereotype of the rustic Venus. Very quickly his paintings got hung on the dining room walls of Kraków's bourgeois and particularly of its petit-bourgeois. These healthy, good looking, florid and colorful heroines contrasted with the sophisticated, always fragile and unhealthy looking Bohemian idols. Two other artists, Wiadyslaw Jarocki i Kazimierz Sichulski, painted numerous images in similar vein. They quickly became well known and well-to-do. Their paintings still fetch high prices, but their work is cliché and is without any serious value except as a market commodity. Art historians have long deliberated the reasons for the low esthetic value of these paintings. It would be easy to say that such an easy subject attracted the less ambitious, yet such a great artist as Wyspiański was also fascinated by these images. Hence it maybe more useful to explore the psychological reason for this fascination. After all, given the artist’s consciousness in its all complexity, the whole approach of looking for lost roots in a lost paradise ought to be too naive.

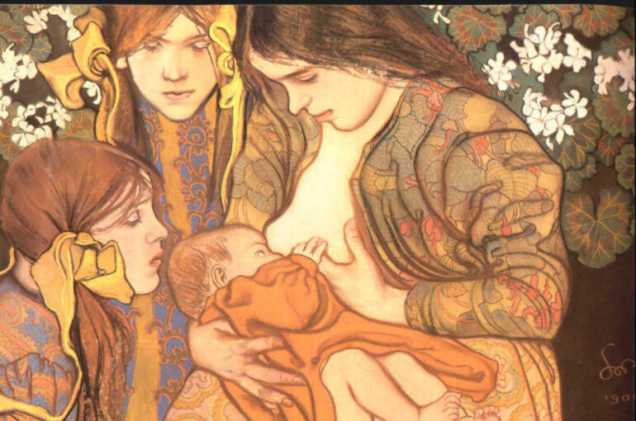

Maternity by Stanisław Wyspiański, 1905, 36x23" pastel, National Museum, Kraków |

The exceptional personality of Wyspiański, the principal representative of this trend, offers us the best indication of motive. His most famous painting Maternity, which features his wife, can be read, in its several versions, as an important part of his philosophy as well as a restatement of the language of painting. He had been successfully following modern European style. This he had combined with his own post-romantic philosophy concerning the history of Poland, in which Kraków, the uniqueness of its locality, and all its heroic past and legends played a special role. His peasant wife with her ugly, rude, non-heroic features, depicts the obstinacy of the class and at the same time its strength. The image also belongs to classical Christian iconography. Wyspiański was the only artist of this period to successful innovate on the motif. Maternity was a small part of a great ambition, monumental in scale, namely, to change this iconography in the spirit of native historical tendencies. A fuller realization of Wyspiański's ambition can be found inside Kraków's gothic Franciscan church, where flowers from the meadows cover whole walls. Wyspiański was well acquainted with floral symbolism, for its knowledge was widespread in nineteenth-century art.

We need to remember how unusual was the personality of this artist. The eminent critic, Tadeusz Boy-ZeleIński, framed it in the following way: "Of all of Wyspiański's phenomenal works, the most unusual was, without any doubt, Wyspiański himself. He was that incomparable creation, sent to us (and why to us?) by a caprice of nature, as if to show how a being from some other realm of existence would look; how, for example, a saint would look if he were simultaneously, in every fiber of his soul, an artist as well as a very keen and sometimes caustic person".

We can say Poland's history and the strength of the peasantry became the two poles between which the soul of this neurotic and sensual artist oscillated. Wyspiański had syphilis, which he got in Paris as usual - and he gave it to many Polish peasant women, whom he admired for their vigorous health.

Another female image that appears in the paintings of this period is that of Polonia. How to define an image so strongly involved with Polish consciousness and unconsciousness?

Polonia is a queen, she is a widow, the Mother of the nation, a widow in despair. She is the symbol of the existence of Poland. But her kingdom is not only of this earth. It is also other-worldly and sacred and thus she is the object of quasi-veneration.

The genealogy of this motif is as old as Polish state, but its depiction changed with time, particularly during the 19th Century in consequence of all the uprisings that sought to liberate Poland from the partitioning powers.

Perhaps the most interesting changes in the portrayal of Polonia occurred following the January uprising of 1863. As prints portraying her became widely distributed, Polonia's allegorical antic robes changed to the most common ones. It is important to note that the uprising also changed the real-life status of many women. Numerous young widows sometimes consciously, sometimes not, began to play the role of Mater Polonia.

Two kinds of images of Polonia dominate the paintings of the end of the nineteenth century. One of them is that of an allegorical and monumental Polonia depicted in all her power. She is proud, has a crown, and is extraordinarily ambitious. She is a fighter, makes people cry, but also gives them hope for a better future.

The second depiction is that of a much more human figure, that of a young widow, almost completely dressed in black, who has suffered but who has decided to forgo remarriage and instead to devote herself to the nation, much as a nun devotes herself in the service to God. What did the artists, who created this image, have in mind. That her nobility consisted of giving up marriage and domestic life? They saw this as the ultimate sacrifice because they, the male artists, believed in the ideal of feminine domesticity.

Among the work of the many and various painters, the great and the less great, we find images of women which correspond to the notions of romanticism and old fashioned views. They mostly presented a sign of woman which equated her with a beautiful object to-be-looked-at. The majority follow Polish cultural stereotypes wherein it is admitted that the body exists but it is a little bit suspect.

Some, who sought to paint an image of woman true to reality, failed because they were not able to rise above the conventional. Some, who insisted on a Polish aspects of that image, also failed. Is it possible to create such images without reference to allegorical figures or literary contexts?

The avant-garde painters who sought to rework the myth of femininity found their spiritual life to be much more difficult. Others, who constantly explored new, modern idioms of painting, were attacked for being "decorative". The paradox of the insular, elitist view of "art for art's sake" is that art is simultaneously sanctified and dismissed as rubbish. That contradictory point of view is met quite commonly when this period in art is discussed.

To paraphrase Griselda Pollock, the image of women which art history defines as passive, beautiful or erotic is a male construct achieved through the conventions that the primarily male art historians have subscribed to over time and the manner in which art has been described and commented upon by them. Accordingly, it is essential that feminist art historians find ways of analyzing art history in such a way as to make evident the contributions of women to our culture.

The type of analysis called for by Pollock and other feminist art historians has not yet been undertaken in Poland. Polish art history continues to shoulder the cultural burden to which the interpretation of Polish paintings by a male dominated culture has subjected it. Can we get Polish art historians to undertake the task of writing a new, feministic oriented, art history?

The above is an edited version of a presentation made to the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo on March, 1996

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |