Jan Matejko: The Painter and Patriot

Fostering Polish Nationalism

Jan Matejko - Self portrait |

Jan Matejko was born on June 24, 1838, in Kraków, the ninth child of Franciszek and Joanna. Franciszek Matejko, his father, was of Czech origin. Born in Kárlové Hradec, he had come to Poland as a tutor in the family of Polish gentry, the Wodzickis. Later on he settled in Kraków where he taught music and directed church choirs. In 1826, Franciszek married Joanna Karolina Rozberg, a daughter of Jan Piotr Rossberg who was from Saxony, to-day a part of Germany. Joanna, whose mother was Polish, retained her father's Lutheran faith. Thus only one quarter of the ancestry of Jan Matejko, the great Polish patriotic painter, was Polish. However, in the Matejko house on Florianska Street in Kraków there prevailed a Polish patriotic atmosphere. Portraits of Poland's heroes - Kosciuszko, Poniatowski - hung on the walls. Polish books abounded.

At a very early age, Jan Matejko was introduced to Spiewy Historyczne (Historical Songs) by Niemcewicz, a set of simple patriotic song poems recounting episodes in Polish history. History was a subject that truly fascinated him. As a child, playing with his brothers and sister (he had eight brothers and two sisters) he liked to stage historical tableaus. Invariably, these scenes would contain the figure of a Polish King.

Jan's second passion, also revealed at a very early age, was drawing. He begun to draw before he learned to read and write and demonstrated and absolutely exceptional talent for it. Already as a child, he copied the illustrations in Niemcewicz's Spiewy Historyczne, drew numerous sketches of Kosciuszko and Poniatowski, portraits of other historical figures, costumes, castles, and so on. It seemed that from the very beginning he found drawing and history to be inseparable. Certainly, his natural tendencies were shaped and strengthened by the atmosphere of his parents' home and the atmosphere of Kraków, a city full of medieval monuments, dominated by the Wawel Hill, the site of the Royal Castle and Cathedral where the tombs of Poland's Kings and the beautiful Sigismund Chapel reminded him of Poland's glorious past.

As it happened, historical events also shaped Jan Matejko's life. At the time of his birth, 43 years had passed since Poland had lost its sovereignty and had been wiped off the map of Europe as the result of three successive and progressive partitions of its territories in 1772, 1793 and 1795. For a time, Napoleon's campaigns had brought the French to Poland where Napoleon created a Polish Duchy of Warsaw but his disastrous Russian campaign brought that to a close. Thus Matejko was born and spent his early years in the Rzeczpospolita Krakowska (the Krakow Republic), a "Free City" created in the wake of Napoleon's defeat by the Congress of Vienna in 1915,. It was by far the freest scrap of territory in what used to be the Polish lands. It remained untouched by the November 1831 uprising that originating in Warsaw sought to liberate the country but was crushed. However, in 1846, yet another attempt at regaining Poland's independence, the Kraków Revolution, unfolded before the eyes of eight year old Matejko. The Uprising failed and led to the annexation of the "Free City" by Austria. Two years later, during the 1848 Spring of Nations, his two older brothers joined Polish general Józef Bem to fight for the independence of Hungary which, like Kraków, was under Austrian rule. One of the brothers perished on the battlefield, the other was forced to live for many years in exile in Paris.

In 1851, at the age of 13, Jan Matejko was enrolled in the Kraków School of Fine Arts. The way this came about was somewhat surprising. Apparently, not the best of students, he was not promoted to the third grade at the Liceum of St. Anne. His oldest brother, Franciszek, who was already a historian and an adjunct worker at the Jagiellonian Library, understood Jan's exceptional talent. It was he who persuaded their father, who thought of art as "just a form of entertainment which would not put bread on the table," to nonetheless transfer Jan to the School of Fine Arts. Luckily for Jan, the father yielded to his oldest son's entreaties and as a result Poland gained a great artist. Jan Matejko studied at the Kraków School of Fine Arts for seven years, that is from 1851 to 1858. He was the most diligent and hard working of all the talented students there. Both the students and faculty at the school referred to him by a nickname suggestive of a combination of shyness and ambition..

Exceptional talent and hard work did not assure Matejko financial success, at least not right away. Jan Matejko, became literally a starving artist. There were days when he did not have anything to eat but stale bread. Nor could he afford to pay the rent for his first studio. He had to move to a smaller one on the ground floor of a building on Krupnicza Street where the lighting was poor. None the less it was in that studio that many of his canvases were created. His first "commercial" success was the sale of a canvas entitled Tsars Szujscy for five guldens to an antiquarian.

In the face of the repressive anti-Polish policies of the partitioning powers, the only force capable of consolidating the people was a perception of national identity. Art played an important role in invigorating this perception. It was understood that art had a "patriotic mission" - to reawaken the national consciousness and kindle the faith that independence could be regained. During the first half of the 19th century, the so-called Romantic Era, this mission had been advanced by literature when, following the suppression of the November Uprising of 1830-31, the work of the three national bards, Adam Mickiewicz, Juliusz Slowacki and Zygmunt Krasiniski, became a kind of national bible and source of moral faith.

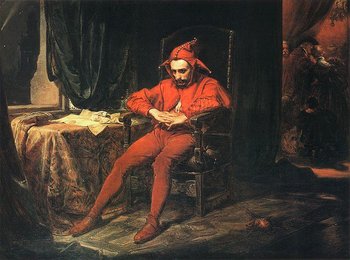

Stańczyk |

Already in 1862, the 24 year old Matejko had completed and won renown for his Stańczyk painting , the full title of which in translations reads: Stańczyk upon the arrival of the news of the loss of Smolensk during the ball at the court of Queen Bona. Stańczyk had been a 16th century court jester renown for his wit and wisdom. The loss of the strategic fortress, but 200 miles from Moscow at once reminds the viewer how extensive the territories of the Polish Commonwealth, the Rzeczpospolita had once been. In the painting, Stańczyk is portrayed as sitting pensive and mortified, a dispatch lying open on a table besides him; through a doorway behind him, the Court is seen dancing oblivious to the tragic news. In Stańczyk, Matejko personified civil conscience and concern for the future of the country. By giving Stańczyk his own features, Matejko imparted to him a part of his own feelings and thoughts of a man experiencing the tragedy of national subjugation and distress about the future of his country.

Skarga's Sermon |

In 1866, Matejko completed the third painting in the series, Rejtan at the 1773 Warsaw Sejm. The 16'x9'3" canvas depicts a dramatic yet futile protest by Rejtan, one of the Sejm's (Parliament) deputies, against the formal approval by the Sejm to the first partition of Poland, a fromality forced on the Polish Sejm by the partitioning powers. The three works form a historical sequence: from a premonition of national disaster, through warning and prophecy, to its tragic fulfillment.

Rejtan at the 1773 Warsaw Sejm |

In 1865, Skarga's Sermon won the gold medal at the annual Paris salon. It was subsequently purchased by Count Maurycy Potocki for 10,000 guldens. In 1867, Rejtan won the gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris. Thus, less than 30 years old, Matejko attained an international recognition. French critics included him among the most outstanding representatives of historical painting in Europe. Through his painting, he succeeded in reminding Europe that Poland did exist -was alive- in spite of political realities.

Matejko's work has to be viewed not only in artistic terms, but also in terms of the social function it performed and continues to perform today and the response it elicits. He considered history as a function of the present and the future. His paintings are not historical illustrations, rather they are powerful expressions of the artist's psyche and his attitude to the world. He created a synthesis of Poland's national history that has found a permanent place in the canon of historical knowledge and patriotic education of successive generations of Poles.

The artist died on November 1, 1893. He lived only 55 years. He left an enormous legacy of several hundred oil paintings and thousands of sketches including a series of drawings featuring all of Poland's sovereigns which is familiar to every schoolchild in Poland.

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |