The Impact of History on Polish Art in the Twentieth Century

A Talk by Feliks Szyszko

Jan Matejko (1838-1893), the most popular creator of romantic visions of Polish history, declared, "Art is a weapon of sorts; one ought not to separate art from the love of one's homeland." Contemporary artists and spectators may find the pomposity and even a certain naivete of that statement are difficult to accept and not only because it was over a hundred years ago that this opinion and many similar ones were expressed. After all, the great adventure of the New Art had already begun, first in Paris, later in Vienna, London and Munich where many Polish artists had studied. Paul Cezanne, the French painter who established the foundations of Art of the Twentieth Century, was a year younger than Matejko. Claude Monet, one of the greatest of the impressionists, was two years his junior. And the tragic end of Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), perhaps one of the best known heroes of Modern Art, took place as early as 1890. Hence, three years before Matejko' s own premature death.Nonetheless, one must not forget that Matejko made the above declaration at a time when Poland, erased from the map of Europe, had no statehood. Many artists, in common with such writers as Nobel Laureate Henryk Sienkiewicz, took upon themselves the responsibility for rebuilding the national identity threatened by the policies of the foreign powers that had partitioned and subjugated the country. Given the title of my talk, one might well ask why I begin with Matejko whose art is after all a reflection of the traditional 19th Century attitude to the world and to the people around him? Being an artist myself, opposed to the use of art for any political purposes and to the regarding of painting as a form of didacticism, I do so to strongly emphasize the impact of history on the art of several significant 20th Century Polish artists.

The question can be raised regarding what modern Polish art would look like but for "The Painted History" created by the 19th century "army" of artists with Jan Matejko as its "commander in chief?" Certainly, it would have look very different. Matejko, in fact, was even more that the commander. He was a highly respected "institution," He was a sovereign.

The Battle of Grunwald by Jan Matejko, 1878, 4.26 X 9.87 meters. oil on canvas, National Museum, Warsaw | ||

| Click on image to enlarge | ||

That tiny, sickly, but unbelievably hard working parishioner from Cracow was considered a national leader, a teacher, a prophet on par with the trio of national bards: Mickiewicz, Slowacki, and Krasinski. The prophesy he made at the time: "Today there are no Polish kings. There is an interregnum. Without no doubt, it will not last long." became the subject of high level official correspondence but it did not personally harm its author; it simply increased his prestige and influence. A time of great changes was approaching.

After decades of forcible Germanization, the imperial government in Vienna had decided to bestow upon the so called "Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria," (i.e., the area of Poland in the Austrian partition ,usually referred to as Galicia), a ceratin degree of political, cultural and economic autonomy. In 1869, Cracow received a considerable measure of self rule and, most importantly, the right to use the Polish language in schools and in the courts. Soon its Jagiellonian University, founded in the 14th century, was re-opened. But the greatest benefit the city derived from this liberalization was in the cultural sphere, because its political role, even within Galicia, was reduced while its economy remained practically non-existent. After the 1873 establishment of the Polish Academy of Arts and Sciences, Cracow became a center for scholarly research, particularly in the humanities; in political history, the history of literature, and in archeology, these activities embracing all three sections of the partitioned country and even extending beyond its frontiers.

During the last decades of the 19th century, Cracow positivists loyal to the Austrian Empire strongly criticized the unrealistic thinking and delusions of Polish romanticism which claimed that Poles were a chosen people with a messianic mission. Such political currents were a reaction to the disaster of the January Uprising of 1863 against Russia, precipitated by the impressment, on the orders of Margrave Wielkopolski of some 1500 of Warsaw's activist youths. The positivist concept of Polish history was somewhat counterbalanced by Matejko, a romantic remnant, a romantic relic in a positivist present. The Cracow conservatists declared a half legendary, daring 16th century court jester, STANCZYK by name, as their patron. Paradoxically, it was Matejko who had first revived theat colorful figure, but gave him quite a different role to play in his huge theater upon canvas. It is significant that Stanczyk, as painted by Matejko, was always portrayed with the painter's face.

If we scrutinize carefully the "last" 138 years of Polish art history, we shall discover the presence of Stanczyk in many works of art from Wyspianski, and Malczewski, through Kantor and up to the young artists of the nineteen eighties and nineties. The attitude of a jester frequently helped many artists to survive and maintain their independence under more or less intolerant or even totalitarian systems.

Stanislaw Wyspianski was born in Cracow in 1869. In 1876 he met Jan Matejko and became his student. From the very beginning he was obsessed with the idea of preserving and evoking the past. His knowledge of history was unbelievable. However, at that time, not being too original, he gained his master's praise. Matejko is said to have proclaimed "He will be Matejko twice over." In fact, Wyspianski came to be both more and less than two Matejkos. He was to become somebody else; not a multiple of Matejko, but one unrepeatable Wyspianski. A great multi talented artist, playwright, and poet effective to some degree in all the media of fine arts, including architectural planning. He was a real Renaissance man who surpassed his teacher intellectually. Gazing at this paintings and drawings we should not forget that Wyspianski came to be viewed as one of the greatest reformers of not only Polish but also European theater.

The years Wyspianski studied in Paris allowed him to escape the influence of his master. To Wyspianski, the Art Nouveau trends revealed the relatedness of the arts, their inter-penetration, their movement towards synthesis. French theater, opera and particularly German Wagnerian drama, opened his eyes to his own literary talents and pulled him in the direction of dramatic works. Wyspianski, however, continued to see himself as a painter, designer and maker of stained glass, of frescoes - monumental works. It was only reverses in these fields of art that tipped the scales of his talent toward theater.

And so this artist created such great modernist works of Poland's national theater as The Wedding and Deliverance. While Matejko's paintings show the artist's complete dependence on his native environment, Wyspianski's works even more so. He is just inconceivable outside of Cracow. Leon Schiller, a famous theater director, characterized Cracow as "the city containing within its walls more legends and elements inspiring drama and the theater than all the other Polish cities taken together" and as "the most theatrically minded city in Poland." Wyspianski was a product of Cracow in the fullest meaning of that word. Except for some three years spent abroad, his entire short, hectic and tense life was spent in his native city which became for him an obsession. In particular the Wawel Hill became a focal point of Wyspianski' s activities. And history is present in most of Wyspianski' s works, be these furniture designs,, paintings, poems, theatrical plays, etc.

Earlier, in 1848 Wawel Castle, or rather the whole of the Wawel Hill, a place of unique importance to the Polish people, had been turned it into an army barracks and partly destroyed by the Austrians. When, due to a more liberal policy, its ownership was returned to Cracow' s community, it inspired patriotic emotions and discussions concerning its shape and destiny. The impoverished city, devastated by the great fires of 1850 and 1866, suddenly retrieved the symbol of the glorious past. After an accidental opening of the tomb of Casimir the Great, one of the most outstanding kings of the Piast dynasty, the ceremonial funeral leading to reinterment his remains became a nation-wide patriotic manifestation.

History is less visible in Wyspianski's paintings and pastels than in his dramas and poems, but his representations of the "Polish Acropolis," as Wyspianski called the Wawel Hill, a the most impressive ever produced. He is but one of those artists who created history themselves. Unlike Matejko, Wyspianski was never presented a scepter. As with most great Polish artists, he was misunderstood, unappreciated, and even humiliated by his compatriots. Wronged, but aware of his greatness, he wrote a poem that began with the words:

did I learn sorrow - but from the living ones."

Melancholia by Jacel Malczewski, 1900-1902, 55x95" oil on canvas, National Museum, Poznan | ||

| Click on image for enlarged sections of the painting | ||

A seated artist is shown in his studio, facing a blank canvas, with his back to the viewer. A black figure stands by the open window at the other side of the canvas. The title of the painting suggests its meaning. Melancholy symbolizes the artist and hence refers to his duty, which is to provide a vision of history. The subtitle, in turn, describes that artist's vision. There is a crowd of figures swirling in the studio who, let us observe, make up the shape of a cross. At the base of the cross are children symbolizing the beginning of life and at the same time of an unfortunate period in the history of Poland. In the middle are men with scythes (the traditional weapon of Polish insurgents), participants in the 19th century uprisings. The left side of the cross, that nearest to the half opened window, is filled with old men near death, prisoners and deportees to Siberia, victims of successive uprisings.

Without going into Malczewski's complex symbolism, let us point out that the image depicts the history of Poland in the 19th century, a period of struggle for independence, a struggle for independence, a struggle which resulted in the deaths of thousands of people. The figure standing on the right is death as well as future deliverance. In other words, the artist suggests, independence will come in the wake of death. The form of the cross filled with figures is a reference to the sacrifice of Christ who redeemed mankind through his death. Likewise, Poland was to rise from the dead through an offering of blood. Hence the open window is a symbol of hope for the coming century, that in which the nation will be redeemed.

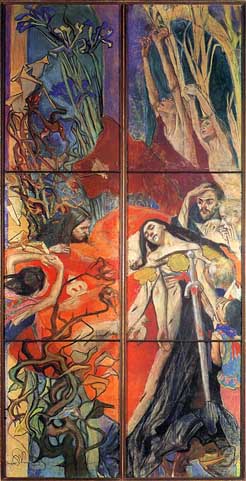

The Polish Hamlet by Jacek Malczewski, oil on canvas, 1903 |

| Flanked by two images of Poland, one old and bound, the other free, radical and revolutionary, the aristocrat, Aleksander Wielopolski, finds the choice a difficult one. The painting symbolizes the dilemma faced by those living in partitioned Poland whether to stay with the status quo or to seek freedom by staging one more uprising, even though all the previous ones had brought defeat and repression. |

Currently, there is a much acclaimed exhibition of Jacek Malczewski' s works in Paris in such an important place as Musee d'Orsay.

"Melancholy's" window opened in 1918 when Poland became an independent state. That, naturally, created quite a different reference point for artistic culture. Art no longer had to act as the treasury of the national memory or create prophetic visions to sustain the spirit. Modernist references were to satisfy the ambitions of the nascent European and democratic society; local references, often visible as those to folk art, satisfied the need for the national legitimacy of the new state, thus justifying its existence.

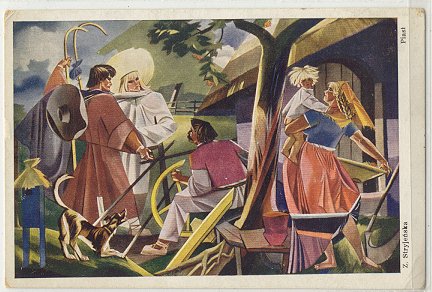

There are many good illustrations of the process. Few in the West, i.e Western Europe and North America, realize how rich was the country's artistic life during 1918-39 period, those twenty years of Polish independence. The names of most art movements and artists of that period, as well as their achievements, remain unknown to most people in the West. Often these achievements were precursory to American and West European avant garde ideas, particularly those of the nineteen sixties and the eighties. However, that's not the topic of my lecture. Let me, instead, present to you a very prolific woman viewed by many as a second rate decorative artist, but whose works are very representative of that period: Zofia Stryjenska. Almong her works there are several historical ones.

Piast by Zofia Stryjenska, oil on canvas, 1932 |

World War II put a stop to many artistic processes, especially as it caused changes in the institutional structure of the country. The implementation of a new political system, based on one party rule and a non-sovereign government (though relics of a multi-party system and sovereignty were preserved for the sake of appearances, especially during the ‘40s) most evidently affected the post-war art world. For the Polish nation as a whole and for people individually, the war had been primarily a traumatic experience and as such became an important element of a search for historical identity, conducted by many artists, especially those of the younger generation. Let me mention but a few.

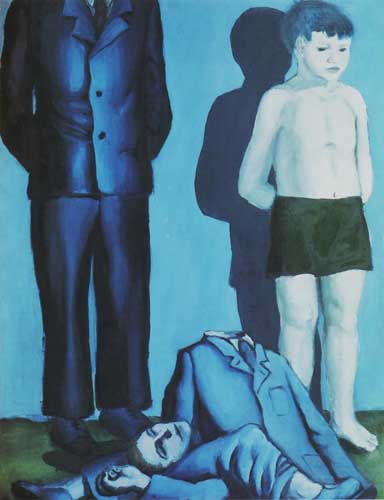

Execution V by Andrzej Wroblewski, 1949 |

Socialist Realism was established as the only way to represent reality. This doctrine is formally and thematically simple. It reminds us of the syllabuses in primary schools which make us believe, after we finish them, that the world is one-dimensional: happy or sentimental, heroic and victorious. "Socialist in content, national in form" even the definition was imported from Moscow. Jan Matejko and other nineteenth century Polish painters certainly never realized that some of their works would become a tool or an instrument in the hands of communist propagandists. The post World War II artists were expected to create the visions of the NEW WONDERFUL SOCIALIST WORLD and to overtake Matejko who was not always ideologically correct. He was too "bourgeois." Thus, some of Matejko's paintings seemed somewhat inconvenient, particularly those representing fights with the Russians. These were carefully concealed. The rest were flaunted as models and pattern formed as free from "Western poisons of any kind." It is not easy to evaluate Wroblewski' s attitude. He was a member of the Communist Party for a while. He painted several pictures utterly in the spirit of Socialist Realism. Certainly he was one of the very few who didn't do it for opportunistic reasons. In opposition to most of the Polish artists he was anti-Western oriented. "Here and now" was his creed. It meant that artists should help in the creation of the New History through their art. Being young and idealistic, he did not realize the danger of the trap and became a victim of his convictions. Rejected by the communists as too "formalistic", despised by some in artistic circles, he died prematurely after Gomulka's "thaw" in 1956" when the Socialist Realism was already over. The circumstances of his death have remained vague (suicide?).

Paradoxically, Wroblewski became later a kind of a master for many younger artists opposing the totalitarian system. The Wprost group from Cracow was one that opted for concrete and expressive art, not "modern" but "contemporary" a record of time and place, of the Polish "here and now." Their program was not so much concerned with aesthetics as with ethics. Art was to stem the tide of schizophrenia in life and the language, to unveil the duplicity of thought, to call things by their proper name: DIRECTLY (the adverb "Wprost" means "directly," "frankly." To expose the lies of propaganda the Wprost group appropriated such idiom. The sociological, journalistic style of the Group often contained references to Christianity. "Hallowed iconographic motifs crucifixions, adorations, and lamentations were brought down to street level." (Czerni)

The group was established as early as 1965 in Cracow as a response to the first exhibition in the Krzysztofory Gallery myself and two of my friends. That doesn't change the fact that we respect each other and could take part in a sharp discussion rather than a fight. We have always been the adversaries, never the enemies!

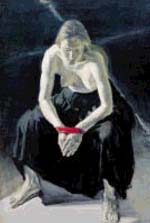

Polonia by Leszek Sobocki, 1982 |

Martial law of 13 December 1981 was a time of repression and depression, yet it also proved to be a period of increased creativity. The intense and diverse independent movement of the Eighties was a sociological phenomenon on an unprecedented scale. Exhibitions, productions, discussions held under the aegis of the Catholic Church elicited considerable response, satisfying an obvious need of the public which instinctively sought refuge and consolidation in solitary resistance. The return of art to consecrated space and of artists to legible symbolism was termed a "homecoming", though looking back, it is evident that a large part of the paintings done at the time were nothing more (or less?) than a record of the period and the emotions it aroused. That art successfully performed a compensatory and therapeutic function. The literal pathos of its iconography was a faithful rendering of the contemporary state of mind and the attributes of oppression such as bars and torn flags as well as the shrouds, floral crossed and broken loaves.

The bad quality and naivete of most of such art works were often criticized. Warsaw's Grzegorz Kowalski, a prominent artist of the independent scene recalled: "Under martial law we were part of society. That's just the fate of the Polish artist. I think that nowhere in the world will you find such resonance, such shared responsibility for national identity. It's a prerequisite of living here, and it's a curse because of the way it constrains us. When society expects emblems, symbols and empathy, can you imagine art just going on turning its back on it? We found ourselves in an anachronous situation: second and first rate artists together in the churches playing the role of Matejkos, Grottgers and Malczewskis!! In some damn European Grand Guignol (famous French puppet theater of atrocities) fate typecast Poles as a victim! Those artists that kept their distance were sidelined because they had much to offer. Their independence proved empty somehow." Kowalski used Matejko's Stanczyk for his composition Solitaire in 1985, but in 1995 made the new part of the diptych entitled Rerun. He made well-known Warsaw artists his protagonists. They have donned the fool's red garb an with their suggestive gestures paraphrase the figures populating Matejko's historical canvases: doomed national heroes, prophets and court jesters. The jester's motley recalls Matejko's heritage. For Matejko is not tantamount to the idea of art as a political mission and its romantic identification with the nation; he also saw the artist as a fool, guided by a spirit of contradiction, a symbol of truth proclaimed against the mainstream and the environment. (Piotrowski)) The work is a bitter comment on some behaviors in the new political situation.

Cracow's Tadeusz Kantor (1915-1990) "can be placed among the select group of the twentieth century's most influential theater practitioners. His work with the Cricot 2 company and his theories of theater have not only challenged but have also expanded the boundaries of traditional and non-traditional theater forms." (Kobialka) Let us say, many critics and theoreticians seem not to see it, the boundaries of traditional and non-traditional painting forms as the painting was almost always starting point of all Kantor' s activities. Knowing Kantor and his wife personally and listening to him frequently I want to strongly emphasize that fact.

As one might call Matejko "a theater director on canvas," Kantor can be named "a painter on the stage." Kantor is know as "a living seismograph" responding to all the most current artistic events all around the world, continually renewed his battle for modernity. No Polish artist but has managed to give the myths, stereotypes, fears and expectations that inhabit the collective imagination such a universal form as Tadeusz Kantor in his "Theater of Death" as he called it himself- beginning with The Dead Class (1975) to his last production Today Is My Birthday. There was a time when he &truggled with Matejko, Wyspianski, and Malczewski, ascending the heights marked out by the national sages and then breaking free of them with the skill of a magician, uniting the roles of the artist as priest and jester. But let's allow Tadeusz Kantor to speak for himself:

|

Wyspianski's fatherland lay in the depth of his heart, but he did not wave his word that was sacred to him like a banner. He branded his countrymen for a phenomenon known today: whatsoever he did they did with "Poland" on their lips. He was brave as hell because when he branded them his attitude had a justifiable rationale when patriotism was the only weapon for rescuing the national existence from the ruthless indifference and crimes of the Great of this World. greatness not such as derives from the triumph of life and thrones, trumpets and drums, the roar of the mob gala costumes we know that kind - but greatness in the face of death - this was Wyspianski's discovery. |

Shortly before his death Kantor painted a big picture, September 1939 Defeat. The painting, of a soldier crucified against a map of pre-war Poland, became a messianic manifesto, illustrating the unchanging destiny of the Pole and his duties to God and Country. The painting is now property of the Cracow Branch of World Association of the Soldiers of AK (Home Army Resistance),.

Jerzy Nowosielski, one of the greatest living Polish painters, once said: "Art is not afraid of propaganda - art is afraid of mediocrity." Let me change one word in that statement and say, "Art is not afraid of history - art is afraid of mediocrity,"

The above is an edited version of a presentation made by Feliks Szyszko to the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo on April 19, 2000

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |