Warsaw's Glorious Royal Castle

An Artistic Legacy of Poland’s Last King

|

|

In 1611 King Zygmunt III Vaza took up residence in the Zamek, moved his court it and rendering Warsaw the de facto capital of the Polish Commonwealth. To accommodate the needed government offices he added three wings to the building, enclosing thereby a pentagonal courtyard that defines the Zamek. He surmounted the west wing entrance with a clock tower. Known thereafter as the Zygmunt Tower, it was destined to become the most easily recognizable motif of the Zamek.

His son and successor, Władysław IV, erected a monument in front of the Castle to commemorate his father. It's a column surmounted by the figure of Zygmunt Ill supporting, with one hand, a large cross and holding a sword in the other. The Zygmunt Column, one of the first secular statues in Europe, graces the Castle Square to this day.

Entering the Great Courtyard one comes face to face with a gothic wail of the original Mazovian Castle. Next to it is an inner tower build by Władysław IV. It's called the Władysławowska Tower.

|

|

Who was Stanisław August Poniatowski, and how did he come to have the wisdom and artistic taste necessary to achieve this, and why was he Poland's last king?

Born in 1732, he was the son of a distinguished and successful Polish general and a doting mother, herself a daughter of Polish magnates, a woman of the enlightenment and high rectitude. She exposed him to a wealth of philosophical concepts and ideas when he was yet young. At 18 he was sent abroad and during the next eight years visited Saxony, Prussia, Austria, France, the Netherlands, and England. He lived for periods of time in Dresden, Berlin, Paris and London. While in Paris, he had the opportunity to see the workings of the court at Versailles, note its manners, admire its taste. His visit to England imbued him with an admiration for that country's political system and social structure.

|

|

The following year, August III, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland died. Thereupon Catherine promised to help Stanisław become the elected King of Poland. Nor was this an idle boast. Poland, then one of the largest countries of Europe and in the minds of its people a sovereign state, was in fact, a protectorate, a vassal state of Russia. It had been so since 1717. The Russian sovereign and his army bad become the guarantor of the Polish nobility's "Golden Freedoms" and of a law the fixed the Polish Army at 24,000 men. And so on September 7, 1764 in a field in Wola, just outside Warsaw, Stanisław was elected King of Poland in a colorful ceremony immortalized in a painting by Bellotto. Although the painting portrays over 7000 persons, it fails to show the gleam of the bayonets of the Russian army that surrounded the field and assured an uncontested election. Even so, the new sovereign was a popular one. Intelligent, cultured and cosmopolitan he was, at last, a Pole. That was welcome for his recent royal predecessors had been all of foreign stock.

Stanisław August started the restoration of the Zamek by completely rebuilding the Royal Apartments and the Grand Staircase which led to them. Located in the south wing of the Zamek, its use is now reserved for ceremonial occasions. The King's architect at the start of this period was Jakub Fontana (1710-1773). His design of the Grand Staircase is resplendent in its Classical style. His father Józef bad also been a distinguished Warsaw architect. Jakub studied in Italy and Paris and his versatile style evolved from late Baroque and Rococo into Classicism. The first chamber of the Royal Apartments is the Guard Room (18) also designed by Fontana. Here on benches along the walls sat the soldiers of the Royal Mounted Guard protecting the King. The room in a classical style and rather austere but if one looks over the lintels of the four doors one finds charming supraportas .representing children with military accessories, the work of Jan Chryzostom Redler.

|

|

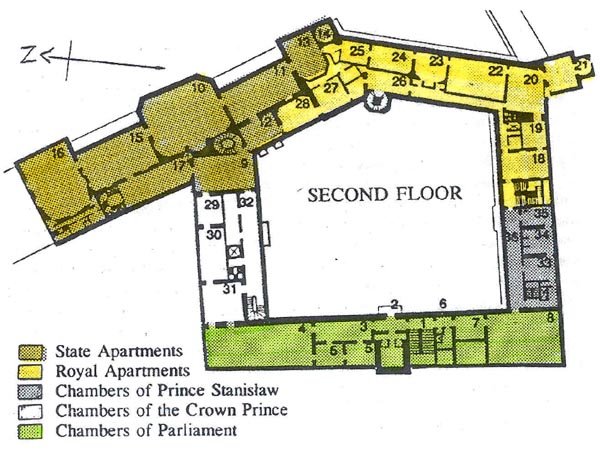

In addition to the Royal and State Apartments, the Zamek houses the Chambers of Parliament (rooms 4-8). These are located in the west wing. The south wing contains the apartments of the King's nephew and namesake, Stanisław Poniatowski (rooms 33-36), while the wing connecting the State Apartments with the Chambers of Parliament houses the apartments of the Crown Prince. Since Stanisław August was a bachelor, the name of these chambers (rooms 29-32) refers to earlier occupants. Today, this latter apartment houses a collection of magnificent historical canvases by Jan Matejko.

|

|

In 18th century, well before the invention of a photographic camera, the detail in paintings produced by this technique must have been truly astounding. The detail is so great that the paintings were used by architects involved in the reconstructions of buildings destroyed during the second World War. In fact Bellotto's uncle had been consistently linked with sorcery; how else, it was said, could such paintings have been produced. In any event, the Antechamber must have instilled in those waiting there a proper sense of awe. Why was the room devoted to views of Warsaw? The message the King intended to convey was that Poland deserved a beautiful capital city and that Warsaw needed to fulfill that role.

|

|

|

A characteristic object gracing the room is a clock in the form of a vase with handles modeled after entwined vines. It was made by Polish artisans from a design by Jean Louis Prieur. A snake's head indicates the time. Over the lintels of the four doors Bacciarelli's paintings represent the four virtues which Stanisław August considered essential in a monarch: devotion, wisdom, justice and strength. At the far end of the room, on a dias, stood the throne.

|

|

The next is a complex of rooms used by the King on an everyday basis to run the government. The decorations and furnishings of these rooms were much altered during the 19th century, and though restored to the style appropriate to the latter part of the 18th, the design is not the original one. The Dressing Room (24) and its antechamber (26) served as waiting rooms for courtiers who were to be admitted to the King's study (25). The staircase in the Wladyslawowska Tower served to admit them here more directly. Adjacent were the Green (27) and Yellow (28) rooms. The former was where the King met with the Royal Council. The Yellow room served as a dining room and thus the site of the famous Thursday luncheons to which the King would invite leaders in the arts and sciences.

If Catherine, in stage managing Stanisław August's election, had counted on a pliant agent, she was to be disappointed. Upon election, Stanisław August promptly embarked on a program of far reaching reforms designed to strengthen the country and render it better able to resist the surrounding powers. Poland's gentry, more than any in Europe, was opposed to centralized power and sought to and succeeded in locating executive authority in the Sejm, or lower house of parliament. Moreover, ever since the passing of the Jagiellonian dynasty, it elected its Kings, albeit in some instances (as under the Vasas) the elections confirmed those who would have become the monarch under a hereditary system. Also, through the exercise of its "Golden Freedoms," the gentry sought equality with the monarch. In the hands of powerful magnates with parochial interests, these same "freedoms," and particularly the Liberum Veto, could be and were used to paralyze the Sejm much of the time.

The resulting conditions of near anarchy presented opportunities not lost on the absolute monarchs of the three adjoining countries, Russia, Prussia and Austria. The Russians, in particular, had managed to make themselves "guarantors" of the "Golden Freedoms" (thereby ensuring continued anarchy), and, as part of the agreement, to a limitation of the Polish Army to 24,000 men. No such limitation applied, however, the number of troops the Russians could station on Polish soil and at Poland's expense, troops that were used regularly to suppress opposition. The Russian Ambassador, for instance, thought nothing of "arresting" the Bishop of Kraków and having him deported to Russia.

Unable to increase the numbers of the Polish Army, Stanisław August founded a crack military academy, the Cadet Corps, so that, should the opportunity arise at a future date, it would be possible to expand the army rapidly. He also proposed constitutional reforms that would have strengthened the monarch's powers and would have also rendered representative government more effective. He proposed abolishing the Liberum Veto, that notorious "freedom" whereby any one member of Sejm could bring its proceedings, or even its session, to a halt. None of this pleased Catherine and by means fair and foul she forced Stanisław August to retreat. The retreat could have been temporary and tactical except that it caused the outraged gentry to resort to another of the notorious golden freedoms, that of forming a Confederation. This ancient procedure allowed the gentry, united in an assembly, to oppose a course of action by force of arms - a form of legalized Civil War. And so they formed the Confederation of Bar, so named after the place in south eastern Poland where the assembly first met. The insurgency lasted four years with Kazimierz Pułaski one of its most brilliant commanders. At one point, it even involved an attempt to kidnap the King (after a brief capture, be escaped though wounded). Finally, it was put down by the combined forces of the Royal and Russian armies.

To Prussia, Russia and Austria the apparent instability of Poland was not to be suffered and these powers resolved on a partial partition of the country. On July 25, 1772 they signed a treaty of partition in St. Petersburg whereby Poland was to lose 29% of its territory. But they required the Polish Sejm to ratify it. Meeting in the Sejm Chamber (8) the body did so with only two representatives voting against it. The action of one of the two, Tadeusz Rajtan, who threw himself in the doorway leading to the Senate Chamber (4) where the final ratifying signature had to be appended, rendering his clothes and pleading with the other delegates to kill him rather than sign the document. It was a grand but futile gesture, one that was immortalized in a famous painting by Jan Matejko.

|

|

Although the topic of this essay is the legacy that Stanisław August left Poland in the Zamek, it would be negligent to leave the impression that this constituted his whole program. He did many other things, called together, for instance, a National Educational Commission, in fact Europe's first Ministry of Education. Through this means he gave new life to Poland's two universities, the Jagiellonian in Kraków and the one in Wilno. He opened many liberal high schools, commissioned a complete spectrum of elementary school textbooks, many so excellent that they were translated into foreign languages and used into the 20th century.

Whereas the Royal Apartments were, so to say, the King's living quarters, where he appeared much of the time in the role of the private individual, in the State Apartments he was to appear in the full majesty of the Head of State. How the complex of rooms was used depended on the occasion and number of people to whom the King gave audience. If the audience was given in the Throne Room (13), then the Marble Chamber (12), the Great Hall (10), and the Knights Hall (11) all served as Anterooms where those to be granted audience had to wait their turn.

|

|

The King found inspiration in Book VII of Virgil's Aeneid, where the King of the Latini welcomes the hero in a temple, or senate house, that is filled with statues of the country's forefathers, its kings from the earliest days, and its heroes; also with a statue of Saturn. The chamber senate house was decorated, moreover, with trophies, weapons and armaments captured in war. That this was the source of the King's inspiration is rendered plain by a quotation in Latin which is inscribed all around the wall of the Knights' Hall (11). In English translation, it reads:

Here are assembled those who suffered wounds for the sake of the nation; those who lead pure priestly lives; those poets of true integrity whose songs were worthy of Phebo (Apollo); those who by their art had elevated life; and those whose contributions have kept their memory alive.The passage comes from Book VI of Virgil's Aeneid (lines 660-664) and it describes bow Aeneas, having descended to the netherworld of the dead finds himself in the Elysian Fields among the most righteous and meritorious of men.

The design of the room is that of Jan Chrystian Kamsetzer (1753-1795). Born in Dresden, Kamsetzer became one of the most outstanding architects in Warsaw. The King sent him on a stipend in 1776-77 to Greece and Turkey and in 1780-82 to Italy, France and England. In doing so the King revealed his Neoclassical leaning.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Finally one comes to the Great Hall (10), or Hall of the Columns. The most august of the Zamek's locations, where Court and State ceremony met: the center of Royal Power. It allowed a forceful demonstration of the idea of authority: through the hall's size, the rich materials employed and the fine works of art displayed. The King sought plans for it from a variety of architects. Eventually a plan by Merlini was adopted as a starting point but its final form is attributable to Kamsetzer. Broad mirrors, statues in deep niches, plain columns and round upper level windows appeared all to increase the size of the Hall. Beyond the Great Hall is the Council Room (15) where the Continuous Council met, and beyond it still the theater or concert hail (16) still so used today.

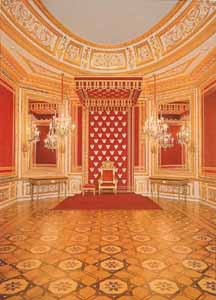

The Neoclassical Throne Room (13) is dominated by its rich gilding and the red velvet the King ordered be used on the throne and walls. The original design for the room and for the carving of the moldings were those of Victor Louis (1731-1800), one of the founders of French Neoclassicism. The Throne itself was designed by Kamsetzer and made by Polish artisans.

To the side of the Throne Room is the small Chamber of the European Monarchs (14). Here hang portraits of George III, Pope Pius VI, Joseph II of Austria, Louis XVI, Gustav III of Sweden, Frederick II of Prussia, and Catherine II of Russia. The paintings of the monarchs are first class; that of George III, for instance, is by Gainsbourough. The whole chamber is an extraordinary work of art devoted by the King to monarchs who were either hostile or indifferent to his country and His reign. The King must have often pondered how to buttress Poland's sovereignty by gaining an advantage over them on the vast chessboard that was this part of Europe in the 18th century.

|

|

|

|

A generation had passed and Stanisław August's educational program had its enlightening effects. The King objected to the runaway Sejm's deliberations. "The fruit is not yet ripe," he cautioned them, but unable to sway them he in the end joined them. On May 3, 1791 the Sejm enacted a new constitution in the Senate Chamber (4), the first one to be enacted in Europe and one proclaiming equality. It was altogether too liberal for the liking of the absolutist Russian Government. Soon Catherine reacted. She persuaded a few dissatisfied magnates to form a Confederation, this one at Tarnowice, and to ask for Russian help to reverse the constitution. Russian armies marched into Poland. At first the Polish army, under the leadership of Generals Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Józef Poniatowski opposed them but soon the King, concerned that the unequal fight would bring much carnage but no success, signaled his agreement to the Tarnowice Confederacy. What followed was the second and disastrous partition of Poland: only 57% of its former territory remained within the country's borders. In 1794, under the leadership of Kosciuszko, the Poles would rise against it. After initial successes, they would be crushed by Russian arms and the third partition would follow, resulting in the disappearance of Poland from the map of Europe for 123 years. Stanisław August Poniatowski. having been forced to abdicate, would spend the rest of his days near St. Petersburg as a guest and virtual prisoner of the Russian state.

The above is an edited version of a presentation made to the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo on September 15, 1993.

Sources of visuals: Polska Akademia Umiejętności, Poczta Polska, and Zabytki Polski.

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |