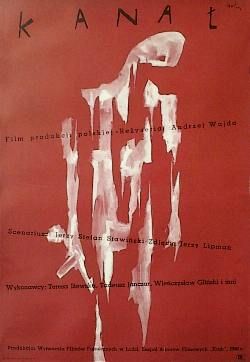

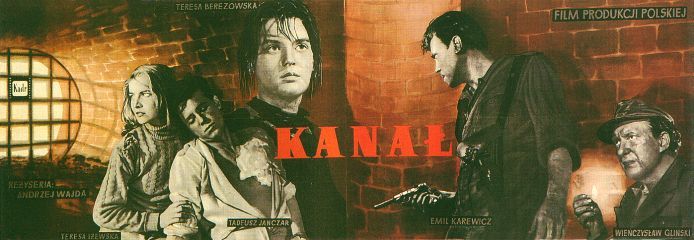

Kanał - A film by Andrzej Wajda

The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth

by Peter K. Gessner

|

|

Andrzej Wajda's 1957 film Kanał is a portrayal of the tragic heroism and the unprecedented suffering of the members of a detachment of Poland's Home, or Underground Army during the Warsaw uprising of August-September 1944. WWII and the brutal German occupation of Warsaw is in the fourth year. Germany's defeat is looming, but still a year in the future. The Soviet Red Army has advanced to the other bank of the Vistula River opposite Warsaw. The Polish Home Army command decides to stage an uprising in Warsaw so that the Red Army will enter a town liberated from the Germans by the Poles themselves, with a Polish Government of sorts in place. Initially large portions of the town are liberated, but Stalin decides to stop the advance of the Red Army and to let the Germans finish off the insurgents, unimpeded. He perceives the Polish Home Army as a threat to his further plans for Poland. For 63 days, the Red Army stands still on the other side of the river while the insurgents are decimated by the Germans. On the 63rd day, out of ammunition and food, the Home army surrenders to the Germans.

The story opens on the 56th day of the Uprising, the detachment of 43 men and women, around whom the story of the film is woven, is forced to give up its defensive position in Mokotów, a district of Warsaw. By this time, the Home Army forces in Mokotów has been cut off by the Germans from those in Downtown area, then still in the hands of the Home Army. Rather than surrendering, the detachment is ordered to proceed to Downtown by crawling through miles of pitch black stinking sewers crisscrossing the town below its surface.

Death awaits each one of them. The detachment's commanding officer Zadra ("Treason" - in the Underground Army everyone was known by a pseudonym, so as to make it more difficult for the Germans to force any one they catch from revealing the identities of their colleagues), having reached Downtown reenters the sewer to search for his detachment after discovering that he was deceived by the fainthearted Kula ("Bullet"), whom he kills, into thinking that the detachment was following right behind through the sewers. Mądry ("Wise") loses his cool and exits the sewers while still short of Downtown and is shot by the Germans. Halinka commits suicide. Smukły ("Slim") is blown up while trying to defuse some hand grenades with which the Germans have booby-trapped one of the exits from the sewers. The badly wounded Korab ("Caravel" - a ship) and Stokrotka ("Daisy") reach the sewers outlet at the Vistula River, only to find their way barred by a sturdy iron grating..

The short story from which the film's screenplay is based was written by Jerzy Stawinski, who took part in the uprising, as indeed did Wajda. When the film was first released in 1957, one of the reviewers, Stanislaw Grzelecki, commented that having

"followed the same underground route downtown from Mokotów as Jerzy Stawinski, and like him, spent seventeen hours in the sewers ... I saw and experienced enough to confirm that Wajda's film is telling the truth. The overall tone and mood of that part of the film and also the individual episodes are in keeping with what really happened. Indeed , I myself and many of those who followed that route, could recall examples of specific persons whose fates confirm almost every minute of this part of the film."Although, in the film, Wajda made no reference to the Red Army's neutral posture during the uprising, viewers of the film, familiar with that posture, must have been powerfully reminded of it. There can be little doubt regarding Wajda's own view of the matter, for - writing about this film on his webpage - he quotes a poem composed during the uprising, adding "This poem speaks the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth ..."

Czekamy ciebie... Ale wiedz o tym, że z naszej mogily |

We are waiting... You cannot harm us! The choice is yours, But know this: from our tombstones |

As for the author of the poem, Józef Szczepaski, one of the insurgents, he, badly wounded, was evacuated, like the film's Korab, through the sewers to the Downtown. Though he made it to Downtown, 10 days later he died in a field hospital there.

Marcel Martin, writing in Cinema 58, Paris (March 1958). made the following comment:

"[T]he gloom, impenetrable and smothering, yet allowing for a vague hope for survival, and the merciless brightness, an illusory symbol of freedom which, nonetheless, involves the immediate presence of death. Having said this - and words do not suffice to express the full intensity of the drama - one must ask: can the viewer really participate in a film in which the horror reaches such unimaginable heights? And the horror and pity, aroused by the misfortunes of the character, are they end [sic] in themselves, since no relief, no hope is offered in the conclusion?"Profs. Paula Michaels and Denise Powers note that Kanal is structured as a Greek Tragedy, so what happens to the protagonists

It may seem surprising that given the town's overwhelming destruction, the decision was made to reconstruct. Ewa Hoffman, in her book 1993 book Exit into History (Viking) addresses the question as follows: "It was one of Hitler's ambitions to make of Warsaw "a second Carthage," and during the city's two-month uprising in 1944 he almost succeeded, with the Germans bombarding the city literally to rubble, while the Soviet Army stood on the other side of the Vistula and watched; the Germans, after all, were doing the work of subduing the Poles for them.The Angst felt so widely in the United States following the September 11, 2001 destruction of the World Trade Center twin towers may render for many more tangible the sentiments of the Polish nation in the aftermath of Warsaw's destruction.

1. The translation of the last two lines of the frist verse, as presented here, differs from that posted on Wajda's website, an effort having been made to render it more faithful to the Polish original.

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Info-Poland | art and culture | history | universities | studies | scholars | classroom | book chapters | sitemaps | users' comments | |||||||