Wesele (The Wedding)

A film by Andrzej Wajda based on Stanisław Wyspiański’s drama

by Peter K. Gessner

Andrzej Wajda being handed the Oscar

from Jane Fonda

Andrzej Wajda being handed the Oscar

from Jane FondaAndrzej Wajda, who received an Oscar in 2000 for Lifetime Achievement, is probably Poland’s best know film director. His 1973 film Wesele (The Wedding) is an very successful adaptation for the screen of Poland’s most famous dramatic work, Stanisław Wyspianski’s play of the same title, a drama difficult for Polish viewers and previously completely inaccessible to foreigners.

Wyspianski (1869-1907) was a very gifted painter, poet, and dramatist. The Wedding, considered Poland’s greatest dramatic work, had its genesis in a real event, the wedding of Wyspianski’s friend, the poet Lucjan Rydel, to Jadwiga Mikołajczyk, a peasant girl from the village of Bronowice, which was then a separate entity but today is part of Krakow.

Stanisław Wyspiański - self portrait

Stanisław Wyspiański - self portraitThe wedding feast took place in the Bronowice home of the painter Włodzimierz Tetmajer who had earlier married Anna, the bride's sister. Both Rydel and Tetmajer were members of the

At the wedding feast there was an unprecedented mingling of social classes with the guests numbering both peasants and members of Krakow’s society. The wedding supposedly lasted three days, though Wyspianski, who came with his wife and daughter, did not remain there for the duration. According to contemporary accounts, he stood by the stove, taking in all that was happening around him. The wedding took place in a magical time, on November 20, 1900, at the start of a new century. By February of 1901, Wyspianski had written the drama and in March of that year it was staged in Krakow. The structure of the drama is that of the that traditional puppet show, or szopka, of the type staged at Christmas time. In such shows, the puppets appear, so to say, on the stage, have their say, and then disappear for a time while other puppets hold the stage. In the drama, the action takes place in a room off the chamber where the dancing is going on; characters wonder in, have their say then rejoin the dancing throng in the other room.

As Wajda notes, in the drama, Wyspianski asks the wedding guests -- Who are you? -- and who were we in the free and powerful Poland of the past centuries.

"Can you win freedom for yourselves and for future generations? Can the Polish intelligentsia and artists lead the peasant masses, which are the only real social force in an economically backward country and civilization. Wyspianski not only asks, he also produces his verdict: you aren't mature enough for freedom, you just whirl in a cursed dance of stagnation and torpor."

Not all the

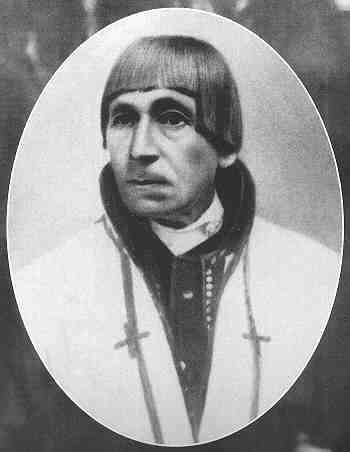

Kazimierz Wayda, the director’s grandfather

Kazimierz Wayda, the director’s grandfatherThe difficult job of adapting the drama to the needs of the screen was undertaken by a well know

writer and essayist, Andrzej Kijowski. He reduced the dialog to an indispensable minimum, retaining those aphorisms, sayings and issues that had become part and parcel of Polish cultural consciousness. Thanks to that and the limited number of shooting locations, Wajda's adaptation is considered as being very faithful to the original. The film was created with an unusual attention to authentic detail. Not the least reason for this was probably the fact that Wajda’s grandfather had been a peasant, the head of the village of Brzesie near Krakow. For the main protagonists, authentic peasant costumes were secured that had been handed down from generation to generation in the environs of Krakow. For shooting of the scenes by the dwelling's entrance and its immediate surroundings, a original old hut was purchased and moved to Warsaw. On the other hand, the interior of the sound stage was made to look like the interior of Tetmajer's home (where the original wedding feast had been held). The verisimilitude of the setting was additionally aided by the Tetmajer family leasing some of the furniture to the film makers. Attention was also paid to visual values of the work. "Wajda's film constitutes, so to say, a mixing of the spontaneity of Breughel’s canvases with the intensity of romanticism. Beautiful work." - wrote a French critic.

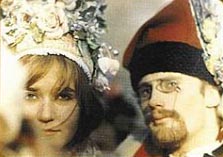

Lucjan Rydel |  Jadwiga Mikołajczyk | |

| Pastels by Stanisław Wyspianski | ||

The film's action begins with the wedding cartage being driven away from St. Mary's Church in Krakow's Old Market Square. Next, passing surrounding villages, the cavalcade reaches the home of Włodzimierz Tatmajer, painter and poet, who is hosting the wedding. The wedding feast begins. The bridegroom is an intellectual. The bride comes from a peasants family. The guests also derive from these two social classes. The feast rapidly becomes lively. Rachela, a young Jewish woman of a sensitive poetic disposition, shows up. It is she, a victim of her own euphoria, who invites in the Chochoł* (pron: Hohow) standing outside the window. Imperceptibly the merry hubbub of the wedding feast begins to be pervaded by an aura of the supernatural. Mysterious ghosts begin to manifest themselves to some of the guests. From their hidden recesses of their souls hidden hurts, complexes, and longings are given voice. And the strongest among the latter is the dream of national independence regained.

*Chochoł: sheaf, a quantity of stalks of wheat, rye, oats, or barley bound together; or a pile of sheaves standing upright or leaning together with two or three laid across the top to turn off the rain. In the fields in Poland sheaves of this type continue to be seen as a way of storage. Near homes, straw is used to protect rose bushes against the winter frosts. In the late evening or at night it is easy to mistake such sheaves for human figures.

Chochołs in Polish fields |  Chochołs as painted by Wyspiański |

The Drama

Act I. A comedy of manners of 38 scenes with dialog that takes place at a very accelerated tempo. One meets the protagonists and gets to know a cross section of Polish society. The action reveals the existing antagonisms between the intelligentsia and the peasantry, between the Poles and the Jews, between the town folk and the rural populous, between the educated and the uneducated, even between men and women.

Bride and Groom |  Rachela and the Poet |

Act II. The drama begins to take leave of realistic poetry. Apparitions begin to appear on the stage. It’s not clear whether these are projections of the thoughts, hopes, and fears of the celebrants or other-worldly beings. Note that with the exception of the ubiquitous Chochoł, they chose but one figure as the focus of their attention.

Act III. Its ending is so suggestive that it reminds one of the play’s beginning in which the dramatist once more singles out the nation’s shortcomings: drunkenness, inclination to day-dreaming, social inequalities, peasant pettifogging (quibbling, cheating), the intelligentsia’s ineffectualness, and the decadence of the artists. Realism again gives way and apparitions, visions and symbols now dominate the stage. The dramatist, in creating these visions, clearly makes reference to romanticism (the scythe armed peasant army that attacked the Russian artillery and made possible Kosciuszko’s victory at Racławice in 1795; the fiery halo on the horizon that recall the interricine conflict resulting from the peasant rebellion of 1846, symbolic birds: the blackbird and the rooster). The symbols have manifold meanings, their strangeness is due to the fact that at some point the live protagonists begin to be used by the symbols rather than the other way round.

The Cast of Characters

Originally, Wyspiański had intended the protagonists of the drama to carry the names of the real persons whom it represented. Under pressure form the theater where the drama was to be staged, he gave up on the idea. Nonetheless, Krakow audiences were quickly able to identify them.

Czepiec holding the golden horn | Characters: Bride Groom Poet Journalist Councilor’s wife - the bridegroom’s aunt Host - Włodzimierz Tetmajer Hostess - the bride’s sister Jewish tavernkeeper Rachela Czepiec Klimina Maryna | Dramatis Personae: Chochoł The Phanthom Stańczyk The Black Knight A Ghost Hetman (Army Commander-in-Chief) Wernahora (Bard and Prophet) | |||

Councilor's Wife |  Stańczyk, the jester | |||

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |