Polish Poster Art

Distinctly Personal Gestures

History of Polish poster art from its inception until about the mid 1970's

by Kristinn R. Rzepkowski

|

Polish Poster Art began during the Młoda Polska, or Young Poland era. It was a period that lasted from roughly 1890 until about 1914. Before this, the most compelling pieces of artwork from Poland were wood cuts from the folk artists of the countryside and paintings. It is not surprising, then, that the first posters were created by painters and were heavily influenced by Polish folk art. The artists, at the time, also had their eyes open as to what else was going on in the world around them. At this time Art Nouveau was all the craze in Western Europe. Polish artistic attitudes revolved around reviving Polish Modernism and following the ideals of Art Nouveau. If we take a look at Sztuka by Teodor Axentowicz (1859-1938) we see that its style is very much reminiscent of Art Nouveau. Another of the early poster artists was Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1807). He was a painter that had traveled all over Europe. His posters set the standard for what was to become of Polish poster art. One of his posters is for a play that was performed only twice in Poland. The drawing and text in that poster are not just illustrations of the play, rather, they are a comment on the content. The difference is that anyone can illustrate what happens in the play, but Wyspiański was able to get to the core meaning of the play with simple images and text. Yet another early poster artist was Karol Frycz (1887-1963), a theater set designer and a painter. In 1904 he designed a poster for Melpomena's Portfolio. It is still heavily influenced by Art Nouveau. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Click on images for enlargements | |||||||

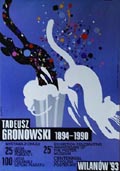

The 20's and 30'sThe turmoil of WWI ended the Young Poland period. Poland, which had been divided between Russia, Austria, and Germany, regained its independence in 1918. With the re-emergence of an independent Poland, the poster began to come into its own as an art form. The architecture department at Warsaw's Polytechnic Institute taught geometric clarity and less devotion to painterly tradition. The Poles began to understand the power of the poster as an advertising tool. They felt that rapid communication could be had through the geometric. Tadeusz Gronowski (1894-1990) became the first Polish artist dedicated solely to posters. He maintained that the poster artist must not assert his personality since the poster is a "communication between seller and public". Gronowski's 1926 poster for Radion soap exemplifies this attitude. The simple geometric image of a black cat going into the wash basin and coming out white personified "Radion does the cleaning for you!" (In 1993, Waldemar Swierzy used the theme for a poster advertising an exhibition of Gronowski's work and in 1997 the Polish Post Office issued a stamp reproducing the poster). At the same time, in the early 1920's, Edmund Bartłomiejczyk (1885-1950), a prominent book illustrator and engraver experimented with poster art. His academic and straightforward style is representative of early Polish Poster Art. In 1935 Bartłomiejczyk began teaching at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts where a more painterly approach to poster art developed that competed with the geometric style of the Polytechnic Institute for dominance. The imagery is very realistic and modeled. Another approach, championed by Tadeusz Gronowski, was very Geometric, so much so, that these artists felt that cubism was the answer. For the next 5 to 10 years much of Polish Poster Art looked very cubistic. In 1937 one of the most influential Polish poster artists came on the scene. Tadeusz Trepkowski (1914-1954), a largely self taught artist, showed off a simple poster aesthetic that favored the literal object without any historic or stylistic allusions. He created a public service poster that showed, placed rhythmically across the poster, three hammer-holding hands and a fourth injured one, brought home the point that an injured hand cannot work. Soon after that came World War II. Between 1939 and 1945, Poland endured the occupation of the Nazis and the Soviets. The country was devastated, with communication, transport, and industrial capacities virtually destroyed, and a population loss estimated at 20% of pre-war numbers. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Click on images for enlargements | |||||||

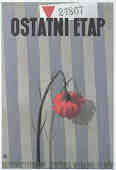

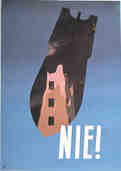

After 1945With the end of the war, the arts were restored. At the forefront of post-war Polish Poster Art was Tadeusz Trepkowski. From 1945 until his death in 1954, Trepkowski produced some of Poland's most memorable posters. His small, hand printed Last Stage advertised one of Poland's first films of the post-war years (1948), a stirring drama of survival and tragedy in the concentration camps. A quiet, eloquent note is observed in the bent carnation, the traditional flower of remembrance in Poland, as it casts a shadow on the striped prison garb. The infamous nature of the camps is again recalled in the identification patch and number. Only the names of the film and the production unit are given; narrative was hardly needed in a country where simple objects historically acquire symbolic meanings. Tadeusz Trepkowski used straightforward composition and pure color again in 1952 for the posters Nie!, and Warszawa. He pared down the imagery only to what was important, specifically, a war ravaged city inside a the outline of a bomb for the simple message "No! ", and a crane hoisting up "Warsaw" to urge the rebuilding of the capital. His strategy of less is more guided many poster artists in a new direction of effective communication. One can see here the direct influence of Gronowski on Trepkowskis work. They both used simple imagery and flat colors to get across an idea. The posters in post-war Poland were commissioned by the communist government. The resulting imagery, besides those of Trepkowski, were bland homages to the dreams of communism. Many of the posters hailed the Soviet Union and featured the happy proletariat. The posters also were less concerned with advertising, because of the centrally planned economy, and dealt more with public service and events. By the end of the 1950's Socialist realism had been dumped in Polish art. The Graphic Arts Department at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts divided its areas of instruction into fine arts, visual communications, applied arts, and poster art. It helped, thereby, to establish what is known as the Polish Poster School. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Click on images for enlargements | |||||||

The New GenerationThe Polish poster artists in the early 1960's knew the styles of the generations before them. The realism that had once seemed adequate and the symbolism that had arisen out of the war no longer satisfied the new generation of artists that would make Polish poster art world famous. These artists used metaphoric imagery which demanded active participation from the reader. One of the "fathers" of this new generation was Henryk Tomaszewski (1914- ). His poster for Henry Moore's 1957 sculpture exhibition evoked a child-like atmosphere, with "Moore" hand lettered across a field of blue and a Moore sculpture atop the 2nd o. It is a calm understatement that evokes the expansive quality of the sculptor's work and asks the viewer to spend some time with the image. Tomaszewski wished the poster to be read, not looked at. The work of many of the younger artists of the Polish School (born in the 1920's and 1930's) varied in style from expressionistic to subdued. Maciej Urbaniec (1925), who had done public service posters during the communist regime, achieved great notoriety in 1970 with Cyrk (Mona Lisa). Gone were the happy clown motifs of many lesser artists, Urbaniec decided to stimulate the viewer with a juxtaposition of history and the circus. Waldemar Swierzy, who has created more than 1,000 designs, brought a painterly background to poster design which shows in the wide stylistic variety of his early work. As much of the Polish Poster Art in the 1970's did, Swierzy's work became very illustrative and let the picture speak for itself. Swierzy's power conies through clarity and caricature. He has the ability to capture the feel of the subject in one, succinct statement. The bete noire of Polish poster artists Franciszek Starowieyski promoted an elitist quality in his work and carefully maintained the facade of the idiosyncratic artist. That is, wrapped up in his own little world, he created posters that suited his tastes and attitudes. He didn't mean for everyone to be able to understand his work nor freely read the text. Jan Lenica (1928- ), who began as a painter, had a free style early in his career. One of the most stylistically diverse of the Polish poster artists Lenica then revived Art Nouveau expressionism in the early 1960's with his poster for Alban Berg's Wozzeck. Whatever the poster, Lenica utilizes the figure to exude a personal statement about the subject of the poster. ConclusionsThe work of the "second generation" Polish poster artists who "built" the Polish Poster School all had one thing in common: a distinctly personal gesture in one form or another. This characteristic is unique to the posters of Poland. Today's Polish poster art still has this characteristic. I was looking at, and reading about the work of Polish poster artists from the 80's and 90's in the 100th Anniversary Exhibition catalog. Many of their posters were commissioned to advertised events, and that they did. But, almost always, there is an underlying dig at some aspect of society. It seems that the Polish poster artist will take any chance they can to express the frustrations they, and their audience share about the status quo. In America it would be like making a public service announcement for the American Heart Association in which President Clinton is the victim of heart disease. It truly would make us change our health habits, but it would also be a statement about the artist's dislike for the American Government. One more thing on modern Polish poster artists: Their posters are still predominately made with brushes, pastels, and paints. One sees very little photography in these posters. To them the only valid expression of one's ideas is by human hand to paper. In a way this is what makes Polish Poster Art unique even today. Each poster is a genuine expression of the artist's feeling toward the subject, not just a catchy slogan or image. The above article has been adapted from the March, 1996, issue of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo Polish Monthly, it in turn being based on a presentation made by Kristynn R. Rzepkowski, a Polish Arts Club of Buffalo scholarship awardee, on February 23, 1996

To see other posters by these and other Polish poster artists check the relevant pages of the Center's Poland on the Web |

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |