An 1891 African Time-Capsule

Excerpts from Listy z Afryki. (Letters from Africa) by Henryk Sienkiewicz

Translated from Polish by Peter K. Gessner

Henryk Sienkiewicz |

Introduction

Sailing from Naples on Christmas Day in 1890, Sienkiewicz reached Cairo on January 1, 1891. From Egypt he took a steamer to Zanzibar, an island some 10 miles wide and 50 long lying off the coast of East Africa. Those were the early days of the European colonization of East Africa and Zanzibar had become a British Protectorate just two months earlier.From Zanzibar Sienkiewicz was conveyed on a British warship, courtesy of Zanzibar’s British Consul Plenipotentiary, to Bagamoyo on the Tanzanian mainland opposite Zanzibar. Though today a backwater some 44 miles northwest of Dar Es Salaam, Bagamoyo was then the capital of the newly created German East Africa "Protectorate" and had been the headquarters of the German East Africa Company which had hitherto operated there with the permission of the Sultan of Zanzibar. Bogamoyo was also to be the starting point of a 25 day walking tour cum hunting trip that Sienkiewicz had planned of the African mainland’s interior. He was accompanied by another European, his friend and fellow countryman, Jan Tyszkiewicz.

Sienkiewicz turned for help in preparing for the walking tour and assembling a caravan of native porters to the White Brothers mission in Bagamoyo. He was bearing a letter of introduction to them from France's Cardinal Lavigerie, the founder of their order.

As it happened, the trip was to last only 10 days, but it was full of vivid impressions, many of which later inspired his writing of a popular children's adventure story: In Desert and Wilderness. Our story begins as he prepares to march out of Bogomoyo at the head of the caravan.

Departing Bagamoyo

It's the day before our departure. Fr. Oskar has shut himself in his room with all our supplies, that is the foodstuff and other provisions which he is dividing into 30kg packs. That's how much each pagazi carries on his head on a march. Beasts of burden are not used in this part of Africa because there aren't any and men take their place. In all of Bagamoyo one might find at most a couple dozen donkeys which are used for work on the plantations. And, to the best of my knowledge, there is but a single pair of horses, belonging to the nabob, Sewa-Hadzi. Camels are unknown, and the horned cattle here are of the Indian variety called zebu. The oxen of this variety likely could be used to carry burdens, but due to their slowness would delay the march, would attract lions, and finally without question it would die from the bites of the tse-tse flies which is found in abundance near all waters.Two or three donkeys would be useful in the caravan, if for no other reason that one could ride on when tired. But, to begin with, they are very expensive. The price of a donkey, which in Egypt runs to a score of francs, in Bagamoyo fetches five hundred. Moreover the tse-tse fly is almost as dangerous to the donkeys as for oxen; one has to guard them at night and finally, one has on their account a thousand difficulties in crossing rivers. There are no bridges, of course, anywhere. One crosses rivers either in dugouts or one fords them, finding shallow places because elsewhere there are masses of crocodiles. Now, where men cross relatively easily, donkeys which present a whole long flank to the current, tend to be carried away by the water. And if the water carries it away, only the crocodiles will find it. So one has to pull the unfortunate animal across by force using ropes, which given their stubbornness, takes hours.

* * *

After half an hour we pass the last Bagamoyo houses. It's eight o'clock in the morning. The heat is already intense, not a cloud in the sky and near the ground just a bit of fog. We walk down a road a yard wide, trodden into the red earth and flanked on both sides by high bushes that form a shady artificial lane. But after a while this roads ends and with it all signs of civilization and the wild country begins. Modern map of the Tanzanian coast and Znanzibar |

We enter even taller grasses that completely hide the world. I continue to be surprised by the absence of any animals, but during the day even in deep African woods silence alone reigns. On the other hand, at night it would be dangerous to walk along these paths, even in company and with a light. But just then we encounter living beings, for a caravan approaches from the opposite direction. A strange and original sight. It's composed entirely of Africans. It is lead by an African wearing what looks like a huge gray wig. It's the front part of the fluffy and furry skin of a baboon. Africans wear such skins on their heads as costume and they look really colorful but very strange. In both hands he holds a staff with a split end and a letter stuck in the split. He holds it at face height and so ceremonially as if he was walking in a procession. ... behind him follow in a long line some 80 or more men carrying elephant tasks. Some are so huge that two Africans carries one. The caravan must be coming from afar, maybe from the Great Lakes, for the men look different from ours, much more wild. They seem unusually timorous. At the shout Nyuma! (stop), the whole caravan not only stops but jumps off the narrow path into the grass, giving us the right of passage. ... We pass them slowly, looking at them with curiosity. There are several wearing, like their leader; magnificent baboon skins. Others, almost naked, have pieces of wood or elephant bone piercing their nostrils, ears, lips.

The Kingami River

We continue on the path towards the Kingami River. Two to three hour walk separates Bagamoyo from M"toni, the place for crossing the river. In all that time we do not pass any huts. To the left and the right, there was no sign of human habitation. ... The nearer the river the thicker the brushwood. We are in a hurry to find shade, for the sun's ray are almost vertical. Around eleven we reached M'toni. A white man came forward to greet us, the river crossing's tax-collector.. He lives here in the vicinity of several African huts and whole weeks go by between his seeing Europeans. When we got there he was having an attack of fever, which was easy to spot by the blushed on his cheeks and his glossy eyes. Our arrival seemed to please him. He invited us under his porch and offered us chicken pieces which he fished out from a pot hanging over the fire. For our part we offered him wine which he drank like a man with fever.The heat was ever stifling. The tax-collector's porch consisted of a reed roof of maybe six feet across. Supported on four sticks, it gave insufficient protection from the sun. But the tax-collector spent whole days under it, since inside his oilcloth tent the intense heat was unbearable. The tent stood right on the riverbank. It was not very high but very steep. That rendered access difficult for the crocodiles of which there are apparently plenty hereabouts since when someone asked the German whether it would be OK to bathe in the river, he grasped his head and said that he would not permit it even if he had to use force to do so. ...

|

In M'toni there is a iron launch which inland bound caravans and those returning to Bagamoyo use to cross the river. The crossing costs a pezo... Caravans from upcountry and not possessing cash, pay on the return trip. There is a cable stretched across the river and the boat is moved along the cable, thus the crossing is accomplished without oars which M'toni doesn't possess.

* * *

In the tent, it was insufferably stifling. Having lifted the edges and having created a breeze, we lay down to sleep, but the mosquitos, which evidently found our blood tasteful, didn't permit us to sleep a wink. I went outside the tent where at least the wind blew from time to time. From time to time I approached the river to listen to the hippopotami, after which I sat down on the hunters chair determined to spend thus the rest of the night... In the end fatigue had the better of me, hence throwing myself on the bed in the tent, I fell into a deep and pleasant sleep, spiting the mosquitos, but not for long for at dawn we were to be on the river.* * *

Having crossed the Kingami, we immersed ourselves in a wood of reeds and brush. The path is narrow, in places muddy. At the side, here and there, puddles or stinking holes full of manure and excreta all churned by the feet of the hippopotami. ... For the first half hour we are surrounded onn the path by extraordinarily compact brushwood because of the lianas which, skipping from one bush to another, lash them together as if with thousands of thinner and thicker ropes. But the mud underfoot begins to lessen and the path becomes drier. Apparently we are leaving the area which the Kingani inundates during the rainy periods. Here and there are trees which we did not see near the river bank. From some of the bushes, hung fruits the size and shape of pumpkins. The brushwood thins out and in the end begins the dry steppe, expansive and on it rare mimosas; in places, clumps of bushes covered with flowers as red as blood - and waist high grass.An African Village

Eleven o'clock. It's the time of the bright glare and silence, when everything seems bleached by the intense heat. After breakfast we go to sleep in the shade of a mango tree, whose dense foliage allows no shaft of light through. We wake up at three refreshed and rested. We decide to move on. ... We walk along the steppe. It's still very hot but the world isn't so terribly bleached as in the midday hours. The sun itself becomes more golden and imbudes everything with that color: the grasses, bushes, trees and the termites mounds, scattered here and there, are all as if covered with a transparent amber coating due to which the sky seems bluer and the surroundings more cheerful. All this puts us in a good mood. We like the journey and the country. It becomes ever more beautiful. The steppe rises perceptively, and round us one can see cheerful small, not very dense, groves outlined with incomparable clearness on the sky. Sometimes these are thickets covering more extensive areas, sometimes clumps of one or more dozen trees. From nearby the countryside looks like an elegant park, from afar as a large forest. But as we approach, the trees move apart and open space appears between them. We see sycamores of enormous size in whose shade scores of people could find shelter. Flocks of toucans fly from one clump of trees to another. When they alight, an intense and loud discussion is heard from among the branches, as if a commission was inspecting the African forestation. After examining one clump of trees, they fly to next one and there begin another conference. On the path we kill two large gallinaecious birds that have grayish fathers, long legs and are uninclined to fly. The cook, M'Sa happily burdens himself with them, assuring us that it's nyama msuri (good meat)...The sun approached the hills on the west. It became as large as a wheel, its lower edge already touching the hills and any moment it was to slide behind them. For some time now we were walking between shrubs. Suddenly, in the deepest brushwood we noticed, under a net of lianas, a palisade and a kind of gate made of short tree trunks. That's the village. We enter,. The central plaza is filled by our people who deposit on the ground the packs they were carrying on their heads. Women and children surround us with a certain curiosity but also with a certain trepidation. The men bring out of the huts their beds, plaited with strips of leather, that is the so called kitanda, on which we sit while waiting for our tent to be erected and put together our own camp-beds...

The night falls and a campfire is started. The fire lights the low roofs of the huts build in a circle in front of which stand or sit groups of Africans, men and women. They are tall and strong. In the red gleam, which requisitely emphasizes the stout muscles of their chests and shoulders, they look like statues chiseled from black marble or sculpted from ebony. The men and women wear only loinscloths, thus one can carefully observe their shapes, particularly, since that all watching us, are motionless and only their eyes in which we see the gleam of the fire, follow us.

Meanwhile the chief of the village, who in spite of the late hour had been somewhere in the fields, approaches hurriedly with evident concern since, since having come before us he whips off his head a kerchief with which he had tied around his hair, and draws himself up like a soldier listening to an order. It's evident that Bagamoyo is but two days journey away. A friendly Yambo! dissipates his concerns, and the absence among our group of any askaris armed with rifles with bayonets, calms him. It would appear that the latter circumstance without reducing his willingness to oblige, puts him in a good mood since, after a short absence, he brings a gift: a goat. A little later he brings a dozen or more eggs, all of which turn out later to contain embryos.

* * *

Morning! The chief comes to offer us his services, but first of all he helps us by scattering the flock of children which has gathered around our tent. But it doesn't help for any length of time, for in a moment the small fry again surrounds us again. Where one looks one sees their rounded heads, staring eyes, fingers being sucked, and big bellies on thin legs.In all villages, the majority of men have seen whites and hence are least obtrusive, the women are more curious, but it is the children for whom the arrival of whites is a spectacle above spectacles.

We got up somewhat late and decided to delay setting out till the afternoon and meanwhile to look around the village. It's larger than it seemed yesterday in the dark for in addition to the huts surrounding the grassless central plaza, other huts are hidden in the brushwood. All around the village is surrounded by the palisade which in earlier times surely protected it from human attacks, and now protects the goats from lions and leopards. The huts are fairly roomy, woven from twigs and clay and round. The umbrella shaped reed roof is set low and creates wide eaves over the hut's walls. Inside there are a few implements: Kitandas, hoes for cultivation of cassava, large vessels made from red clay for storing water, here and there a couple of javelins against the wall - and that's all.

It's the driest period. The work in the fields is finished and hence the whole population is in the village. The women and men sit in deep shade under the eaves and are weaving mats. Their loins are covered with pieces of calico, frequently in very bright colors, and as a result, many colored patches dot the shade.

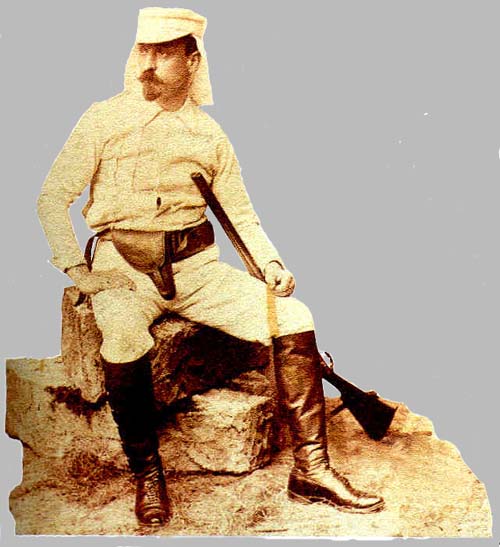

The pombe

Near Muene-Pira … I and my friend stayed behind with several Africans to hunt. We sent the rest of the pagazi ahead with instructions not to stop until they reached the old King with whom we were to spend the night. Instead, having come to a certain village on Muena-Pira, we are surprised to learned that our people have already set up the tent and have gotten ready to bivouac. Henryk Sienkiewicz in a safari outfit |

We came across just such a ceremony. When we approached the village, over 300 Africans came out to greet us. They stand as a wall, as if they had wanted to bar our way. It may have been five o'clock in the afternoon, the sun had descended quite low and was bathing itself in red glow in which they looked wild and picturesque. It was truly an African sight. The tribes living in the littoral area are distinguished by their strong build, hence I saw chest and shoulder of truly museal proportions. Most wore calico loincloths, but some their hips girdled with dry grasses. Many wore pelele in the lips. I also noticed that many had their hair set very artificially into a horn over their foreheads as per the custom of the U-Zaramo nation. Armaments, other than a few javelins, I did not see.

The whole crowd was under the influence of the pombe an in a state of excitement. From afar we heard the hubbub, shouts and laughter, which however became muted as we approached. Our people were at the back of the crowd and looked worried, unsure whether we would let them stay and take advantage of the windfall that had come their way, or whether we would decide to move on.

Both of us felt quite tired, since it had been the second march of that day, and the sun was almost setting. We were tempted to remain, if for no other reason so as to watch the African dances and the festivities, but it could not be. If we stayed, our people would surely get inebriated on the pombe and that could result in some quarrel or brawl between them and the locals …

Our tent had not yet been put up and the camp-fire lit when pepe Muene himself brought us drinks. ... I tilted the container which he handed to me to my mouth. It was woodland honey, very cool but so full of caterpillars that I pushed it away with disgust, letting the host know with the aid of gestures that he should retain for himself such delicacies. On the other hand, the pombe in the other container, seemed to me a delightful beverage. Now I understood why our people preferred to risk their skin to stopping at the preceding village.

After two, or really three marches I extraordinarily thirsty, so for a long time I couldn't tear the container from my lips. I was quenching by this one means both my hunger and thirst, because pombe was not only cool, not only a bit sour like the leaven of bread dough, but in its taste it reminds one of bread, and the thickness of soup such as is eaten by our Mazurian folk. In the darkness I could not see its color, but at that moment I was completely oblivious to it, as also to the fact that, from time to time, somewhat more solid pieces were making their way down my throat. My friend indulged himself no less than I and Muene seeing that - glad that he had pleased us - begun to jump up and down from happiness like David in front of the Arc, repeating: Pombe msuri! Pombr msuri! In fact no drink had refreshed us so quickly. Only we couldn't understand by what means. Africans can get drunk on pombe, which in reality is none other than diluted and somewhat fermented dough. Maybe one can explain this on the basis that Africans living far from the coast and not used to alcoholic beverages and are hence easily inebriated.

The Wami River

We move at first light and by seven o'clock we are by the River Wami. It's the second African river which we are to cross. The banks of the Wami are not covered with brushwood as were those of the Kangami, but by a true virgin forest. The river flows rapidly down the middle of its bed. Nearer us its current is blocked by huge boulders. As a result it branches and creates small lagoons filled with almost standing water. High tree pyramids form reflections in the lagoons which, also reflecting the blue of the sky, seem bottomless.Festoons of lianas, arching from tree to tree, hang just above the water and, further back, create a semblance of curtains draped over the doors of darkened woodland temples. Inside the light is ceremonial and shaded as from a gothic window. Trunks of the trees loom in the shapes of altar columns and the inner recesses are completely shielded from the eye. Every where there is calm, silence; waters framed by a wall of trees - a strange, almost mythical retreat.

A Polish 1929 postage stamp |

Here and there, flowers rain and petals, blood red and pink, lie in the shade on the water's mirror. In places where a thick carpet of bushes doesn't cover the ground, one can see the dark and moist earth, similar to the soil used in hothouses. Suspended above it is a light lace of ferns. Higher, the trunks are wrapped with lianas as if with ship lines. Finally, its all crowned by a cupola of leaves: green, reddish and yellow, large and small, shaped like fans, swords, feathers, and arrowheads.

The forest is composed, as usual in equatorial regions, of every kind of tree. Palmettos, dragon trees, rubber trees, sycamores, tamarisks, mimosas - some thick and crouching, others slender with narrow shoots. Sometimes it's impossible to tell which leaves belong to which tree, for it all is entwined. ...

We stand for a long time in silence and reverie as we take in the view. But in the end it's time to cross the river. That's an alluring moment for the Wami is famous for its crocodiles. Just in case, I first take my revolver and shoot five times in the water, after which without much hesitation I step in into the water the company of several Africans...

The crossing is really unpleasant. The water which in the riverbank lagoons is almost still, becomes in the river's bed very rapid. In some measure this protects one from the crocodiles, but it makes walking across it difficult. Aware that whom the current will grab and pull into deeper and calmer waters, the crocodiles will surely find, I lean with all my strength on the javelin which I got from one of the pagazi, and yet I advance with much difficulty.

Then, the javelin breaks in my hands. I grab Francis around the neck and hold on and continue to advance. The river bottom is full of submerged boulders. Sometimes the water is up to my keens, then its up to my chest. It's some pleasure, to feel around in front with one's foot while standing on a submerged boulder, expecting that in the hole sits some thing that might grab one by one's calf.

In the end we reach calmer water, and from it climb onto a low rock beyond which there is just a tiny lagoon that borders directly on the forest.

The Fever

I kept feeling increasingly strange. At times it seemed to me I was feverish. We hurried our steps and begun to run as in an attack. The sun behind us moved ever lower and our shadows got ever longer. It was already after sunset when suddenly in an clear field Tebe-hunter stopped. Our men followed his example and begun to remove the loads off their heads and shoulders.- What is going on - I asked FrancisAh! So this is Gugurumu? I had thought this name was that of a village, a settlement of at least a few huts - instead around there was no trace of humans – it was steppe as far as the eye could reach, here and there bunches of trees, otherwise emptiness.

- Gugurumu! - answered the interpreter.

But then it turned out that among the grasses there was a depression, a hole, and at its bottom some water, more precisely a soup, thick, yellow, muddy. After the long march, the men jumped to it greedily. I wanted to stop them, but Bruno calmed me maintaining that an underground spring would replenish the water level as soon as it went down. And it was true. There is an underground spring. This circumstance makes Gugurumu and its surroundings on of the best hunting territory on the whole coast, since all the other waters thereabouts, including the Kingami, which flows several miles to the south, are, because of the vicinity of the ocean, salty. All the animals must come to this hole containing fresh water. Given that the surroundings are without human habitations, there is a plentitude of animals. In particular boars, called nidri, are found here in abundance

While removing the grass from the area for the tent, I saw scorpions that would bring pride to their kind, for they were as big as shrimp. We ground several into the ground with our heels. After the tent was set up, I dispensed provisions for dinner, but I felt ever worse. The headache returned and I had pain in the joints, particularly the knees. Meanwhile the night fell quickly and a full moon appeared in the sky. Depositing my hat, belt, canteen and field glasses I begun to circle the tent at some distance, so as to cool my head in the evening breeze and get rid of the pain in the joints which, in spite of the marches, didn't allow me to sit still.

But as soon as I walked away some score of steps, Tebe-the-hunter and Francis joined me like shadows.

- M'buanam kuba, here you cannot move away from the camp-fire.I returned. I felt ever worse. I couldn't sit, or lie down, or stand, perhaps jump out of my skin. M'Sa handed me dinner, but suddenly I felt an untamable revulsion to food. Using a thermometer, I determine that my body temperature was 103.1. That was an enormously high temperature for Africa where the normal one is 98.6.

I took our my diary, with which I never parted, and in the light of the camp-fire I wrote in large letters for that day "Fever." A bit later begun the struggle in my brain between my habit of noting everything and the fever. I didn't give in however, and in spite of temporary hallucinations, I continued to reason as a man in possession of his senses. I remember that purposefully I didn't use the thermometer again, for the thought came to me that if I saw 104 or more, then I would understand that there was nothing for it and I would given in to the illness, but I didn't want to surrender, rather I wanted to break the fever and return home.

I realized that at Gugurumu it would overcome me, but if I were in Bagamoyo in the care of the missionaries, I wouldn't give in. To that end I called Bruno and instructed him that at dawn half the men be ready to march out without the tent with just my bed, on which in case it was needed they could carry me.

My travel companion insistently wanted to come with me. I put it to him that he needn't do so, that nothing will help me on the trip, and that within a day I would reach Bagamoyo and the expert care of Fr. Stefan. After a long discussion it was decided that if I should feel better on the morrow, he would stay and take advantage of the hunt in Gugurumu, and if not, he would accompany me.

In the meantime, a huge dose of quinine cut down my fever. Only exhaustion and total uncaring about everything to such a degree that when, while sitting at night in a hunting chair by the tent, I heard the grunting of a lion, it didn't make any impression on me,. It neither waken my hunting instinct or that of self-preservation. It was simply as if I belonged to a different world. I would have thought that the grunting had been a hallucination of my hearing, but it was too distinct, too deep. Moreover, our men heard it also.

Epilog: On arriving back in Zanzibar, Sienkiewicz was carried directly from the ship to the hospital. He soon learned that during his absence, six of the Europeans he had met in Zanzibar had since died. When his companion went to the bank to exchange some money, he was told that all three European bank clerks had come down with an epidemic fever and had also died. Hearing this Sienkiewcz wrote, "only now did I understand clearly that there is no joking with these climates." He decided forthwith to take the first ship that was sailing for Europe. A couple of week later he was in fact able to leave. It was not the climate but malaria that caused the fevers these Europeans were succuming to. It was not until 1898, however, that the transmission of malaria through the mosquito was established. Moreover, a significant proportion of Africans native to Tanzania have partial protection from the ravages of malaria because they have inherited the sickle cell trait from their parents; the trait's incidence runs as high as 35 to 50% in some Tanzanian tribes. Possession of the trait does not prevent being infected with malaria, it does make the symptoms of malaria much less severe. Sadly, however, those who inherit the trait from both their parents develop, in time, sickle cell anemia, a disease which is usually fatal. In present day Tanzania, mortality from malaria continues to be high: Tanzanian hospitals record about 100,000 people, mostly young children and pregnant women, as dying of malaria every year, but the total mortality could be higher because a number of patients die in their homes. A debate currently rages in Tanzania regarding whether DDT, the insecticide that was banned in 1983 because of its effects on the environment, should be brought back in an effort to control the disease.

Further reading:

"Malaria Dreams: I was invincible in Africa -- until the mosquitoes got me." By Tanya Shaffer in Salon, the Internet magazine: -- A vivid account of an encounter with malaria.

"Resurgence of a Deadly Disease" by Ellen Ruppel Shell in The Atlantic, September 1977: -- Provides some measure of the extent of the problem.

"Doctors probe incredibly high rate of malaria cases among Marines in Liberia" Assocaited Press, September 10, 2003

"Marines in Liberia contract malaria: Military doctors speculate that failed chemoprophylaxis might be to blame for an outbreak of malaria" Infectious Disease News, Ocotber, 2003

"Liberia Marine Malaria: Inexcusable" Grunt Doc +, September 09, 2003

Mosquito: The Story of Man's Deadliest Foe by Andrew Spielman and Michael D'Antonio, London, Faber and Faber, 1998. 247pp -- An excellent longer, detailed but lucid coverage of many aspects of the scourge.

The Miraculous Fever-Tree: Malaria and the Quest for a Cure That Changed the World by Fiammetta Rocco, Harpar-Collins, 2003. 348pp - highly recommended.

First given a dramatic reading at the September 22, 2003 meeting of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |