The Search for the Word - A tour of the exhibition

by Danuta Bromowicz

Curator of the Jagiellonian University Library's Szymborska Exhibit

A poetic biography

|

|

- My mother has been found, my grandfather glimpsed;

I dreamed up for them a table, two chairs. They sat down.

Once more they seemed close, once more living for me.

The next one, Smiech (laughter) recounts how, when a young girl, she became enamored with a certain student; her interest and feelings, however, were not being reciprocated. So, she wrapped a towel around her head, hoping he would ask her whether she was suffering from a bad headache, but in vain. She tried various other way to draw his attention, nothing worked. Then a poem about her sister, who

- does not write poems,

and is unlikely to suddenly start writing poems

and she does have a sister. This is the sister who, when she takes a trip, sends postcards, writing each time that she will describe everything fully in the next one, but never does. Instead,

- When my sister asks me over for lunch

I know she doesn't want to read me her poems.

Her soups are delicious without ulterior motives,

Her coffee doesn't spill on manuscripts

|

|

Birthdays (Urodziny) is the title of the next poem. We celebrate these, from the very first one until the very last one; we receive a lot of gifts, but at some point these become just too numerous and we no longer know where to put them ... on the floor? ... high up on cupboards?.. And yet some are very expensive gifts. We would like to think carefully about all of that, but eventually we really donít have the time.

Next, in beautiful poetic prose, an essay Szymborska wrote about the sea. She was asked to contribute to an anthology on the subject. So she wrote about the sea, a sea in Krakow. No matter that there is no sea anywhere near Krakow. For a poet, that's not a problem. Why, during the Jurassic era, there was a sea there and traces of it can be found in the countryside around Krakow. The beautiful castles we can admire atop of the hills, their location is the bottom of that sea. And when Szymborska walks along Royal Street, which used to be called The 18th of January Street, and then along Karmelicka Street, towards the center of town, she is walking along the seashore. As she walks, she can see various antediluvian animals ... ... ... well, you need to read the rest for yourself.

Album Rodzinny (The Family Album) comes next in our poetic biography. Over the years, we collect various photographs. We mean to write captions, but ... we are always short of time. When, years later, we pull out these photographs, we cannot even spot ourselves. Is this my head or someone else's? Am I the fourth from the left or the fifth on the right? And so it goes.

A love of privacy

Then, a beautiful poem, Podziekowanie (Thank You). She has these unexpected thoughts. Usually we thank people we love or like, but she thanks people for whom she has no such sentiments. Why? Well, if she goes to the cinema with a person for whom she has no special sentiments, she can concentrate on the film. And if she goes with such an individual to theater, she really gets to appreciate the performance, and if she takes a trip with someone of this sort, she manages to take in and remember a lot of detail. But if you are in the company of someone you really love someone, then itís a bit different: you worry whether you are being sufficiently tactful, whether the person you are with might get upset, etc., and that makes it difficult to concentrate on those other enjoyable matters. So she is thankful to those she does not love.

And the writing of a resume: that's something she does not like. Because, well .... what kind of resume could it be. It's not really the story of her life, just some unvarnished facts that people will embellish as they wish. Szymborska's resume, I must admit, is very short indeed. But people are always very curious: Did she have a husband? Does she have children? yes or no? On the very day when it was announced Szymborska had been awarded a Nobel prize, two women journalists, Anna Wikond and Joanna Szczesna, decided to put together and publish her biography. Wislawa Szymborska was not much interested in the writing of this biography. Gazeta Wyborcza, the Polandís largest circulation daily, has published three substantial excerpts from the forthcoming biography and the two journalists visited the Szymborska exhibition at the Jagiellonian Library and found some interesting details there also. They showed Wislawa Szymborska what they had written and she liked it. She read through it, made some corrections and the book will be out in May.

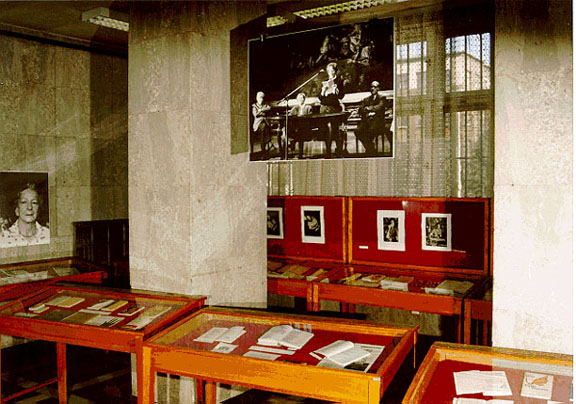

Nine slim volumes of poetry

|

|

The next section is devoted to her literary debut. Her first poems appeared in several of Krakow's literary magazines, thus in Inaczej and Walka. These were quite good poems for someone starting out. But her first volume of poetry, Dlatego Zyjemy (This Is What We Live For), is, in our judgment now, not that good. It contains poems from the period of socialist-realism, written as if it were an assignment. Maybe we could find two or three good poems there, but, in truth, the subject matter of these poems is pretty indigestible. From the same period we have a volume titled Pytania Zadawane Sobie (Questions Asked of Oneself). But also we have some family photographs including those of Wislawa Szymborska's mother, Anna Rothemund, and her father, Wincenty Szymborski. Immediately after it was announced that she had been awarded the Nobel prize, the two journalists descended on Kurnik, the town nearest to the place where she had been born and where her father had worked and there they were able to locate these photographs.

Obmyslam Swiat (I Meditate Upon the World) is our title for the next period of her creativity. This is the period post 1956, an important date in the history of Communist Poland, for it marked the end of the Stalinist period. The title comes from that of one her poems of this period: Obmyslam Swiat - Wydanie Drugie (I Meditate Upon the world; Second Edition). She had reconsidered the subject matter of her poems. During this period she publishes the volume Wolanie do Jeti (Calling to Yeti). It's poetry of a high standard. Her poem Nic dwa razy (Nothing twice) which has become the text of a popular song in Poland, also dates from this period..

Sol (Salt) is the title of the next volume of poetry she published. We are always interested when and under what circumstances are poems written. And for two poems in this volume we have that information for Szymborska provided it in an interview. I wanted, so to say, to bring Wislawa Szymborska to the exhibit. I felt that through her own words, spoken in interviews, her presence would be more keenly felt.

Rozmowa z Kamieniem (Conversation with a Stone) is a another very beautiful poem. I knock on the door of a stone and I say to it, "Let me in, I want to see what is inside, what's there in those halls, I want to know for just myself, I won't tell anyone else." And time stone answers, "I cannot let you in." She persists and the stone gives various reasons for refusing. She keeps asking though and, in the end, the stone responds that it cannot let her in because it simply does not have a door.

|

|

The next section is titled Allegro ma non troppo. It refers to Wszelki wypadek (Just in Case). "I always spot something amusing when faced with exaggerated seriousness," she said in her 1973 interview with Nastulanka, "However, too much joviality and fake enthusiasm saddens and sometimes frightens me. That is not a poetical program, its simply the way I am presently." From the volume, we have a poem in which she is much distress, though itís unclear whatís is all about. In the end, however, we learn that she has lost her umbrella. The poem's title? Przemowienie w Biurze Znalezionych Rzeczy (A Speech at the Lost and Found Office).

The poems in her seventh volume of poetry, Wielka liczba (A Large Number), show Szymborska's great sensitivity to the prosaic, everyday events which encompass the political and social scene within a broader metaphysical insight. Here, we have two different manuscript versions of the poem Cebula (The Onion). These provide an insight into her "search for the word." Interested as we are in the art of poetry, we get some insight into how her creative process works.

The Jagiellonian Library possesses a number of manuscripts of poems by the Nobelist. Some came to the Library in 1991, when Szymborska donated to the Library the manuscripts of her deceased husband Adam Wlodek. She is very shy person; so she never mentioned that among her husband's manuscripts there were some of her own. When a colleague of mine asked her whether she had any of her own manuscripts that she could donate to the Library, she replied, "No, I do not have any, I throw everything out." Next day, however, she called and said that she had found some, after all.

Ludzie na moscie (People on a Bridge), is a volume for appeared in 1986. It was written during the difficult years of Martial Law, a time all Poles found tragic and painful.

Niektorzy lubia poezje (Some Like Poetry) is the title of a poem from her most recent volume, Koniec i Poczatek (The Beginning and the End).

Other works

We display some new poems, the latest to be printed, not yet published in a collection, Chmury (Clouds), Milczenie roslin (The Silence of the Plants), and Trzy slowa najdziwiniejsze (The Three Strangest Words). Now, however, she finds she has no time in which to write poetry. I had a conversation with her about this, I asked her whether she has written anything since being awarded the Nobel, hut she has not, she simply cannot concentrate sufficiently. She awaits the day when she will again have the time for it.

Epigrams and limericks, yet another form in which she has written. Limericks are a special witty Irish form of poetry, very fashionable among poets now. Her limericks have not yet been translated. Here is one in the Polish original:

- Pewien rybak no Gwadelupie

Co byl zdania ze to hardzo glupie

Znac do wyspy tylko jeden rym

I w szalupie popisywac sie nim

Przy biskupie lub w grupie przy zupie.

|

|

|

|

A unique exhibit is made up of illustrations she has drawn for books: for a children's book (Mruczek w Butach) written in 1948 by her husband, Adam Wlodek; for Jan Stanislawki's 1946 English language manual; and for Michal Kleofas OgiŮski's 1962 Romanse. Another form of graphic art she puts her hand to is the creation of humorous postcard collages using bits of newspaper. Her purpose is very utilitarian, for she uses these postcards to send messages to her friends through the mail. However, her friends treasure these works of art highly. In this section is featured also a strangely titled interview with Szymborska: Przpustowosc Owiec (The Throughput Efficiency of Sheep). It is a discussion of the use of bombastic language by official as a way of hiding the absence of substance and meaning.

Translations

In the next section are her translations of poetry from Bulgarian, Slovak Yiddish, and French. She most likes Theodore Agrippa d'Aubign?(1551-1630). At the opening ceremonies of the exhibition at the Jagiellonian library she said she would devote more time to translating his poetry.

Finally we feature translation of her poetry into a variety of languages. Those into Italian are really noteworthy because they are published in such beautifully edited editions. We feature translations into English by Czeslaw Milosz, by Stanislaw Baranczak, and by Joanna Trzeciak. Here also are the translation into Swedish by Anders Bodegard, a former faculty member of the Jagiellonian University, where he taught Swedish. It has been said that his translations read excellently well. By making her work thus accessible to the Royal Swedish Academy, he is given credit for making it possible for Szymborska to receive the Nobel Prize.

Based on remarks made on the occasion of the April 1997 showing of the Szymborska Exhibit at the University at Buffalo. Recorded, translated and edited by Peter K. Gessner. First published in the May-June 1997 issue of the Bulletin of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo. Photos by Jerzy Duda

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |