Delightful Inventiveness, Prodigious Imagination

by Regina Grol

|

|

It is the misfortune of literature written in smaller, or politically less powerful countries, that - regardless of their quality - the literatures tend to be unknown outside of their native realm. On rare occasions, however, credit is given where it's due and outstanding writers enter the international arena. Such, most fortunately, is the case of Wislawa Szymborska, the 1996 Nobel Prize laureate in literature.

Although not the first Polish writer to be so recognized )- she was preceded by four Polish-born Nobel Prize winners in Literature: Henryk Sienkiewicz (1905), Wiadyslaw Reymont (1924), Czeslaw Milosz (1980), and Isaac Bashevis Singer (1978), who wrote in Yiddish, ) Szymborska is the first Polish woman to gain such distinction.

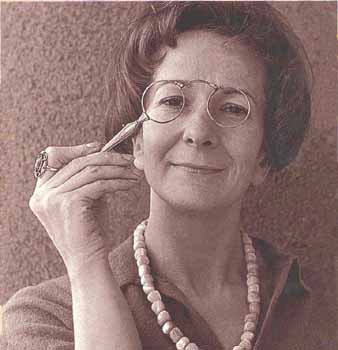

Born on March 2, 1923, in Binin near the city of Poznań, since 1931 Szymborska has resided in Krakow. She studied Polish Literature and Sociology at the Jagiellonian University and has been affiliated with literary journals in the city. Szymborska published her first poem in 1945. She has continued to write poetry ever since. Yet, she is not a very prolific poet. As she revealed in a recent interview, she "revises, revises and revises" and often after all the revisions, tosses the poems into the waste paper basket. Consequently, her literary output consists of several (11) slim poetry volumes. It was clearly the quality, not the quantity, that impressed the Swedish Academy.

Szymborska's Nobel Prize was not only a literary success, or success of esteem, but a very substantial monetary success. The prize amounted to $1.2 million, the highest sum since the inception of the Nobel awards, and probably a monetary prize without precedent for the writing of poetry.

To Szymborska, a rather selfeffacing and modest woman, the award came as a shock. Painfully shy of the public spotlight, at 73 the poet suddenly found herself in the limelight, besieged by the media, rich and internationally famous. Until then, though her poetry was well known in Poland and by few poetry aficionados abroad, Szymborska remained, essentially, a very private person. She shied media attention, lived in a small two bedroom apartment on the 5th floor in a building devoid of elevators, a 5th floor walkup!

Yet, while modest in her needs and here demeanor, Szymborska has been ) and continues to be ) intellectually most probing and daring. In her Nobel speech, delivered in Stockholm, for example, she did not hesitate to question the authority of a Biblical sage. She engaged in a polemic with Ecclesiastes and questioned his assertion that "there is nothing new under the sun."

Szymborska's poetry is rather deceptive. It is very accessible on the linguistic level, yet it contains multiple layers of meaning. Her delightful inventiveness, prodigious imagination and wit have led the Nobel Prize Committee to declare her "the Mozart of poetry." Yet, despite her playfulness, she is a very serious and profound poet. The subtle irony of her verses makes her a challenging poet as well. And it is precisely that subtle irony that makes her ) as the Swedish Academy acknowledged ) a difficult poet to translate. This has not deterred translators. Szymborska has already been translated into 16 languages and translations into additional languages are likely to follow.

In an interview following the announcement of her Nobel Prize, Szymborska declared that she sees poetry "everywhere even outside poems: in prose, in film, in painting." In her poem titled Some like Poetry, however, she is hesitant to define what poetry is.

- ‘I don't know and don't know and hold on to it

like to a sustaining railing,'

the poet states. But she does know. She knows very well.

Her poems are probing and complete messages. In attenuated, sometimes even colloquial language, Szymborska raises original and unsettling questions about human nature, the precariousness and sense of human existence, about mankind's place in the universe. Her poetry is never confessional or personal. She transforms her observations, issuing from personal experiences, into poems of a general nature, touching upon the universal or even the cosmic. The poet never gushes emotionally, nor does she allow herself any poetic pontification or jeremiads. Her penchant is for crisp philosophizing and raising more and more contradictions. She is known by her friends as homo ludens, a playful, fun loving, very witty person. These aspect of her personality are abundantly evident in her poetry. Yet despite her distinct irony and the profusion of wit in her poems, her is not lightweight or facile poetry.

While she is capable of using language with dexterity, even panache, she often resorts to simple, sometimes even colloquial phrases. She can, when she chooses, imbue her verses with wondrous musical qualities, onomatopoeic effects and catchy rhyming patterns (for instance in the poem Jeszcze (Still), but primarily she strives to convey an intellectual message. In each of her poems she raises a question, or makes a carefully considered point.

Szymborska captures the attention of her reader not with pretty language or musical effects, but with the power of her ideas, with the originality of the questions she raises, with her unique perspectives or insights. Most of her poems are clever mini-treatises on some aspect of our existence. It is a poetry which is both stimulating and refreshing.

The above is the text of introductory remarks made the author to an April 13, 1997, dramatic reading of Wislawa Szymborska's poems which Dr. Grol had organized. It was first published in the May -June1997 issue of the Bulleting of the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo. Dr. Grol is the compiler and translator of Ambers Aglow, An Anthology of Contemporary Polish Women's Poetry, Host Publications, Austin, TX, 1997

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |