|

Witkacy: Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz 1885-1939 by Mark Rudnicki Dramatist, poet, novelist, painter, photographer, art theorist, and philosopher, Witkacy was one of the leading members of Poland's poetic and artistic avant-garde of the first half of the 20th century. |

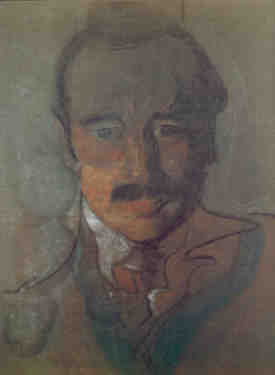

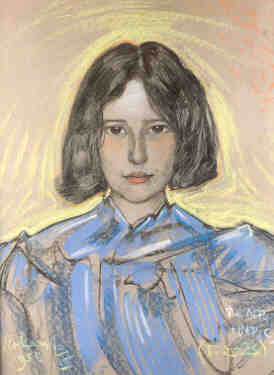

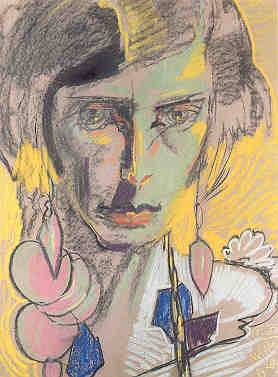

Self-portrait, 1938 pastel Witkacy |

He was schooled at home and pursued diverse interests to promote creativity in painting, music, photography, literature, science and philosophy; however, his most important and lasting creation came much later in life; shortly after he returned from his military service in Russia, he created Witkacy -- a combination of his last and middle names. He began signing his experimental paintings, and most of his correspondence by this name, or some variation of it (Witkac, Witkatze, Witkacjusz, Vitkacius, Vitecasse), which helped to distinguish him from his famous father with the same name. Unfortunately, this creation was simply a manifestation of an identity crisis. Due to his eclectic education, Witkacy attempted throughout his life to distinguish himself in many outlets, as a painter, aesthetician, playwright, novelist, and philosopher, and, through whatever means necessary: marriage, sex, drugs, or alcohol. All of these efforts to justify his existence proved futile during his lifetime, as he was privately and publicly, for the most part, unsuccessful; only posthumously did his work receive proper attention, and, subsequently, national and international success. Today hardly a season goes by without a performance of one of his dramas or an exhibition of his paintings. His dramas and paintings have followers all over the world.

He was determined to be an artist and, in his youth, his artwork received some favorable critical attention. While he enjoyed modest success and found kindred spirits for a while in the Formist group in Krakow, he remained an outsider to the cultural and literary establishments of his day. Most, criticized the artist and his theories as the ravings of a maniac or dilettante, who produced nonsensical works with no redeeming qualities. For philosophers, he was intriguing, but lacked technical training; for writers, he was a painter trying his hand at writing; for painters he was too 'literary.' Additionally, his methods and lifestyle - as a drug experimenter, alcoholic, and bohemian sex addict - seemed to overshadow his artistic output. Witkacy, likewise, found little alure in the movements of the day such as abstract art, futurism, Dadaism, and constructivism. Alienated from all of these avant-garde movements, he found no group to support him and no followers to reinforce his fragile ego.

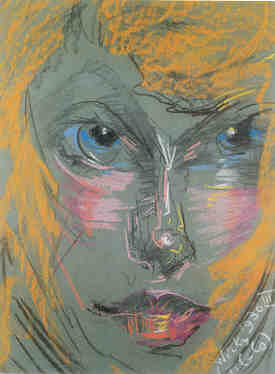

Witkacy: multiple self-portrait reflected in mirrors, 1915-6. Photograph |

In 1918, after being released from the Russian Army, Witkacy returned home to an independent Poland. During the next twenty years, he had an incredible outpouring of activity. He wrote over 30 dramas, including The Madman and the Nun or Nothing is so bad that it cannot be made worse; The Mother, The Water Hen; he wrote three novels, with Insatiability gaining the most attention. He painted dozens of formist paintings and hundreds possibly thousands of portraits. In the 1930's he established the Artistic Theater in Zakopane, and devoted the last years of his life to philosophy, most notably to his magnum opus, Concepts and Principles Implied by the Concept of Existence (1935).

Eccentric lifestyle

When exploring the work of a particular writer, Witkacy often found it ''a matter of importance'' to have an image of the thinker's face (gęba) in front of him. However, he offered no detailed explanation as to why he needed this, just that it was essential to see what the philosopher's ''mug'' looked like. I would like to proceed in this presentation in the same way, however, a difficulty immediately arises:which photograph of Witkacy adequately represents his mug? He photographed and painted hundreds of self-portraits, illustrating himself as a buffoon, drug addict, priest, doctor, and a madman. There is a famous photograph, taken in Russia, presenting Witkacy in his officer's uniform of the Pavlovsky Regiment, seated in front of two mirrors. The mirrors present multiple (four) Witkacys from different angles.

Witkacy: poses, 1923-31. Photographs |

All of these manifestations of Witkacy represented in the photograph, including his life must be viewed as inextricably linked. In fact, "familiarity with the personality of Witkiewicz. . . is the indispensable condition for fully understanding the most profound sense of his philosophical work;" [1] for his life and his work proceeded along parallel lines. In all of his endeavors Witkacy sought answers tc the most fundamental philosophical questions regarding the Mystery of Existence:

"Why am I exactly this and not that being? at this point of unlimited space and in this moment of infinite time? in this group of beings, on this planet? Why do I exist if I could have been without existence?"According to Witkacy, this Mystery can never be solved, but it can be experienced. In his theory of art, he claimed that through the experience of true art (primarily painting, drama, music) an individual intensifies his or her feelings of individuality and affirms his/her own uniqueness in the face of an alien universe. As a result, the individual restores temporarily what Witkacy calls Metaphysical Feeling of the Strangeness of Existence, which simultaneously creates a childlike sense of wonder and anxiety.

Witkacy attempted to restore this metaphysical feeling, this sense of wonder about life, by creating a world of play, fantasy, and grotesque ghoulishness: a fantastic world of childlike wonder and apocalyptic horror, where the divisions between the dream world and reality cease to exist. This world was not only created in his artistic endeavors but also in his interactions with others. In these encounters Witkacy often resorted to tricks, jokes, and conscious manipulation to reveal the unknown lurking in the depths of the human psyche. The only fate worse than death for the artist was the lack of originality. For him the world was born anew every day in a different unexpected form.

With this in mind, Witkacy engaged on occasion in unusual behaviors. During a conversation, for instance, he would suddenly turn his back on his companion. A moment later he would face him again, now however, peering at his companion through holes cut out in the centers of bisected ping-pong balls otherwise covering his eyes. Or, in the middle of a conversation, he would adopt the role of a drunken tsarist officer or imitate a close friend. He had a special gift for impersonating his friends' voices and mannerisms.

Another of his gambits was to crouch down as low as possible when opening the door to greet a guest and then slowly to draw himself up just to see the surprise on the face of the person on the other side. On one occasion he ordered a veal cutlet, then put it into his wallet -- much to the disgust of the waiter.

He kept a formal list of his friends in order of importance. His best friend would be in the first position and so on. In the event that a "friend" somehow irritated him or, perhaps, pleased him in some way he would be demoted or promoted on the list as the case may be. Witkacy then would send a formal letter to the person indicating his new position. Occasionally he would publish the list in the local newspaper.

Perhaps his favorite activity was to devise strange scenes of unusual events. He manipulated his guests (sometimes rather cruelly) to perform bizarre roles creating unique and sometimes tense situations. Sometimes he would move around during a party explaining to selected guests the role to be played and convincing others to act different roles. Or he would establish the roles to be played by his group of friends before hand and take them to the party to create a unique event. Once the famous Polish poet Aleksander Wat was cast in the role of an Italian or Spanish aristocrat. Wat performed his role excellently and took it so much to heart that eventually, having consumed a considerable quantity of alcohol, he came to believe in his aristocratic descent. The night ended with a terrible melee in a local restaurant where Wat ran amok and from which he had to be forcibly removed. Witkacy could not contain his delight. The game had been a success!

Another interaction happened when the Avant-garde poet Julian Przyboś, accompanied by the painter Wiadyslaw Strzeminski, came to visit Witkacy in Zakopane to discuss the theory of Pure Form, about which Witkacy published numerous articles. The two artists were hopeful to have an "essential conversation." Unfortunately, for these very disciplined artists, their hopes for a philosophical conversation turned into a frustrating experience or, perhaps, a "happening". Years later, Przyboś described the event as follows:

The room was hung with pictures, all of them in the Witkacy style, so well known later on -- pictures he produced in such a quantity that they could be counted in the hundreds . . . It was the first time I ad seen them and the impression was unpleasant: the glaring cacophony of colors and the confusion of lines in the Secession style, as if washed down with soapsuds and "licked clean". What else in the arrangement of the room stuck in my memory? A washbasin: a tin bowl and a pot of water. These I remember because, every few minutes, Witkacy interrupted the conversation, went out, came back and washed his hands! I suspect that he did it to make the situation "strange". Another thing he did, seemingly with the same purpose, was to shout out, without any reason, two proverbs: one French: Apres nous le deluge! and the other the notorious Russian one, which he later immortalized in his book on narcotics: 'I would be famous for heroism if not for my hemorrhoids!'How could a man, who wrote theoretical treatises, who had such lofty ambitions in art and philosophy, practice "buffoonery"? The answer is quite simple: Witkacy's actions, running in and out, washing his hands every few minutes [3], repeating the French-Russian sayings, were not only an attempt to "make the situation strange"; they were, in fact, an answer to his guests' reservations about the practicality of his theory. They were attempts to create a sense of Mystery. In other words, Witkacy practiced buffoonery as a method of discourse, as expression of his philosophical theories, and/or as a creative medium much like a "happening."

Strzeminski, who took things in earnest, started to talk about Pure Form right away. But Witkacy did not say anything new; he just repeated all those generalities, already known to us from his publications. How should a picture be painted to fulfill the postulate of Pure Form? -- Strzeminski asked . . .

Witkacy's only response was to repeat that the end of art was approaching and to continue to screech, Apres nous . . . The atmosphere was getting tense, I felt intuitively that our host was more and more embarrassed, that he was lacking self-assurance, that it was only to summon up courage that he performed his ablutions and kept repeating the tedious French-Russian tag . . . It went on like that for a while when, suddenly, Strzeminski grabbed his crutches and cried: 'Let's go, I cannot look at it any longer!' pointing at the pictures on the walls. 'It pricks the eyes!'

Witkacy giggled 'satanically'. He said that his pictures were not art, but a portrait-painting firm. [2]

Painting and Drawing

Italian landscape, 1904. Oil |  Australian landscape, 1918. Pastel |

Composition (with dancer), 1916, Pastel |  Composition - Lady Macbeth, 1933, Pastel |

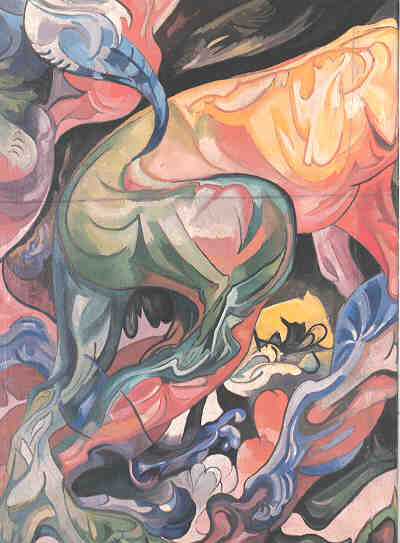

Flight (detail), 1921-22. Oil |

I am not sure how many viewers are having this spiritual experience affirming their own uniqueness in the face of an alien world while looking at the representation of the painting in the browser's window. Perhaps it is the limitations of the browser. Yet, I have seen the original, and I must say that I did not really reflect upon my place in the universe. If, viewer, you are like me and you are not having this experience, I have to tell you that Witkacy would not shoulder the blame for this. He would blame the spectator for not being open to the metaphysical experience.

Around 1925 Witkacy abandon artistic painting. Instead he established the Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz Portrait Painting Firm. He established the firm primarily as a source of income. His paintings and plays were not very successful and produced little income and he now had a wife, Jadwiga, to support. Out of all of his endeavors, the portrait firm was the most popular and the most lucrative. Witkacy's portraits became so popular that in 1928 he wrote the guidelines, which clearly explained the rules and the various types of portraits available. First let's look at the types:

1. Type A -- Comparatively speaking the most "spruced up" type. Suitable rather for women's faces than for men's. Slick execution, with a certain loss of character in the interest of beautification or accentuation of "prettiness".I would like to emphasize two of the 16 rules:

2. Type B -- A work making greater use of sharp line than type A, with certain touch of character traits, which does not preclude "prettiness" in women's portraits. Objective attitude to the model.

3. Type B+ supplement -- Intensification of character, bordering on caricature. The head larger than natural size. The possibility of preserving "prettiness" in women's portraits, and even of intensifying it in the direction of the "demonic."

4. Type C, C + Co, E, C + H, C + Co + E, etc. -- Subjective characterization of the model, caricatural intensification both formal and psychological are not ruled out. Approaches abstract composition, otherwise known as Pure Form.

5. Type D -- the same results without recourse to any artificial means.

6. Type E -- Combinations of D with the preceding types. Spontaneous psychological interpretation at the discretion of the firm. The effect achieved may be the exact equivalent of that produced by types A + B . . . etc. . .

Rule #3. Any sort of criticism on the part of the customer is ruled out. The customer may not like the portrait, but the firm cannot permit even the most discreet comments without giving its special authorization. If the firm had allowed itself the luxury of listening to customers' opinions, it would have gone mad a long time ago. . . Given the incredible difficulty of this profession, the firm's nerves must be spared.

Rule #10. Customers are obliged to appear punctually for the sittings, since waiting has a bad effect on the firm's mood and may have an adverse effect on the execution of the product.

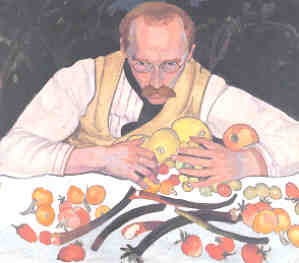

Portrait of Ignacy Wasserberg, 1910, Oil |  Portrait of August Zamoyski, 1918. Pastel |

Portrait of Anna Nawrocka 1925, Pastel |  Portrait of Anna Nawrocka, 1939, Pastel |

Portrait of Bohdan Filipowski, 1928. Pastel |  Portrait of Nina Stachurska 1930, Pastel |

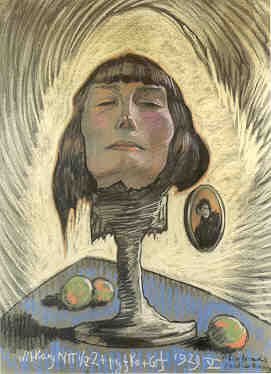

Lastly two portrayals of Maria Nawrocka. The notation on the type C 1929 Portrait of Maria Nawrocka, provides the information that Witkacy had not been smoking for two and a half days and that while he made the drawing he was under the influence of a small beer (piwko in Polish but here spelled pyfko) and caffeine. The 1926 Portrait of Maria and Wlodzimierz Nawrocki, on the other hand, is a type A and D. The portrait of the female model in the center is of Type A, beautifying the sitter, while the male model is portrayed in type D, a subjective interpretation, here achieved without the aid of mind altering drugs.

Portrait of Maria Nawrocka, 1929. Pastel |  Portrait of Maria and Włodzimierz Nawrocki 1926, Pastel |

Witkacy in the theater.

Witkacy' s theory of theater is based on his theory of Pure Form in Painting. For Witkacy the theater offered more than any other art form could; it was a total fusion of the senses: auditory and visual which made immediate contact with the spectator's sense of metaphysical wonder. Witkacy's theory of theater resists the 19th century well-made play by opposing imitation of real life, naturalism, symbolism, and psychological techniques. He claimed that the purpose of the theater is not to get the audience emotionally involved in the play - involvement of which they are sick and tired in real life - nor should a play attempt to teach or solve social problems as in Shaw and Ibsen. Instead Pure Form in the theater is revealed by allowing the possibility to deform both real life and the fantasy world freely in order to create a whole whose essence would be defined by the performance itself, avoiding preoccupations with psychological consistency or building action based on assumptions that apply to real life. In other words, in his dramatic works everything is possible. Witkacy attempted to recreate a dream like world on stage.He wrote: "On leaving the theater, one should feel that he has woken up from some strange dream in which even the commonest of things possessed some strange unfathomed charm characteristic of dreams incomparable to anything else."

This dream-like world is the only way, according to Witkacy that the theater can fulfill its task, which is to transport the spectator into an exceptional state, the state of sensuous comprehension of the Mystery of Existence which, in its pure form, cannot be reached so easily in the passing of daily life.

So Witkacy created plays for the theater that were not easily understood. In fact, one of his first plays to make the stage during his lifetime (Tumor Brainowicz at the Slowacki Theater) caused such a controversy amongst the actors that they refused to perform the work after the opening night. Today his dramas appear to be in vogue. In the 197Os, his play A Madman and the Nun was performed at Towson University in Washington DC. The director of the theater was rather nervous about the reception of this "experimental play". The play was such a success that the next year when they performed an Arthur Miller play (a safe bet for success) people of all ages called in to complain because they wanted to see another play by that crazy Polish writer. It has since been performed in many theaters accross the United States, indeed the world.

While Witkacy creates a dream like world in his dramatic works, there are common themes in his works. I would like to comment on three common ones:

First, the setting: - The action of his plays is usually set in the scenery of what could be described as a period of transition; the old order is falling to pieces or at least nearing its end. The masses are in revolt. The atmosphere is one of fear, insecurity and political confusion. An atmosphere where anything can happen and usually does.

Second: - Witkacy realized that it was impossible to liberate the drama completely from real life. As a result he employed parody, i.e. parasitically adapting past epochs, using elements of past dramas in his own work. So he playfully borrows from traditional dramas adapting them in new ways to create mystical results. Shakespeare's character Richard III in Witkacy's work New deliverance. The Mother, subtitled An Unsavory Play in Two Acts and an Epilogue, is a parody of Ibsen's famous work: Ghosts: A Domestic Tragedy in Three Acts, playfully replacing domestic with unsavory and abandoning the traditional third act in favor of a mysterious epilogue. The first two acts of Witkacy's work mimics the conflicts of the 19th Century bourgeois world in which behind moral idealism one finds the harsh realities of life. Superficially, at least, the thematic motifs expressed in The Mother can be found in Ibsen's Ghosts: dysfunctional family. Both main characters Leon and Osvald inherit their fathers' weaknesses both physically and morally. The Mother Alving and Eely keep up the image of the stable and moral family unit, while underneath all of this is a crumbling family unit.

However, the epilogue is anything but traditional. Act two ends with the death of the mother. In the epilogue, the closing scene, Leon, the main character, finds himself outside of the normal dimensions of space and time in a room without doors or windows. On stage his mother's corpse lies on a pedestal; and his mother 24 years younger, who is pregnant with Leon appears alive and active with his father, who was executed a long time ago, along with the rest of the cast. The drama closes as all the characters escape from the room and Leon is annihilated by six automaton workers who arrived through a large pipe from above.

Third theme: - death and ghosts: This theme appears in various forms such as vampires, mummies, corpse-like automatons (robots), and characters either overcoming obvious deathblows or simply returning from the dead. His bizarre attitude toward the concept of death occurs in the subtitle for Dainty Shapes and Hairy Apes the subtitle reads A comedy with Corpses. Immediately we are struck by the awkward subtitle. Usually tragedy has corpses not comedy. However, in Witkacy the corpses do not always remain dead, they return. I have already mentioned The Mother who returns in the epilogue while her corpse lies on stage, and the father also returns from the dead. Walpurg in The Madman and the Nun returns soon after committing suicide while his dead body still lies on the floor; the main character of the Water Hen is shot "straight thru the heart" only to return in the next act without surprise from anyone. The Mummy in The Pragmatists is shot repeatedly with no ill effects; there is a snoring corpse in the New Deliverance; the Shoemakers refers to the future of mechanized corpses. In the drama A Small Country House, the dead mother returns as a result of her daughters' séance and she participates in the family's daily activities.

So one can see that his dramas are not traditional literary works. They are attempts to move beyond the traditional in an effort to restore the mystical function that the theater once had, especially to create metaphysical wonder in the spectators.

Witkacy's death

His death, like his birth, Witkacy was an experiment with space and time. On September 1, 1939 the Germans invaded Poland from the West; on September 17 the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the East. The following day, Witkacy, in a physically weak state (he couldn't hear or walk very well due to injuries) and in emotional despair, decided to take his own life. His companion, Czeslawa Korzeniowska, upon waking and discovering Witkacy's corpse, claimed to have seen "two Staś's." Even in death, he seemed to play with life. However, the legend of Witkacy does not end there. In 1988 the Polish Ministry of Culture decided to bring the remains of the dramatist home for a proper burial reserved for great figures in Polish literature. The body was exhumed from the hastily made grave in Ukraine. Upon examining the X-ray of the coffin, a Witkacy scholar determined at once that the remains in the coffin were not that of Witkacy, for the corpse had a full set of teeth, whereas Witkacy did not. None the less, the officials proceeded with the elaborate celebration, only to face accusations of scandal afterwards. Most of Witkacy's admirers were in fact quite pleased that almost fifty years after his death he was able to practice buffoonery once more.1. Leszczyński, Jan, Filozof metafIzycznego niepokoju

2. Przyboś, Julian. Linia i gwar, Krakow 1959, vol. Ipp. 147-149.

3. Witkacy obsessively washed his hands throughout his adult life. Daniel Gerould argues that when Witkacy studied in Krakow. he acquired more than theoretical instruction; due to his bohemian lifestyle, he contracted a sexually transmitted disease, which may have led to his obsessive-compulsive behavior.

The above is an edited text of a December 12, 2001, presentations sponsored by the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo ana the Polish Studies Program at the University at Buffalo.

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |