The Story of Panna Maria, TX. Part I

The First Polish Americans Find Hope in Texas

by Kathryn G. Rosypal

Executive Editor of Naród Polski, a publication of the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America

The year 1854 saw the first of three large groups of Polish pioneers emigrate with their families from Upper Silesia to Texas. These, the first Polish settlers in America did find hope in Texas – but that's ALL they found! No town, no church, no homes, in fact no shelter of any sort, as they expected. They found sage brush, mesquite and one large live oak and a geographical terrain like nothing they had ever encountered in Poland.|

|

In all, three large groups emigrated from Upper Silesia to Texas, in 1854, 1855 and 1856, respectively. The future settlers lived in small villages that were scattered through Upper Silesia's countryside. They were all Catholics. The population of the five counties whence the settlers came was officially listed in 1855 as 288,390 of whom 90% were Roman Catholic, 8% were Protestant and 2% Jewish.

The key to why so many people in a relatively small region decided, after having lived there for centuries, to uproot themselves and sail clear accross the Atlantic lies in the conditions in which the future settlers lived in Upper Silesia. Those conditions, and the favorable news they received from Texas combined to render emigration an attractive option. Soon conditions on both sides of the Atlantic changed, rendering the Silesian settlers influx a one time event. For the brave souls who made the journey, it took anoter 15 yeas to finally identify themselves as Americans, stand up to their neighbors and fight for their rights as American citizens playing an important part in our country's history.

Factors Motivating Emigration

Poverty: Upper Silesia was a region known for the poverty of its peasant class. Among the various reasons for the future settlers emigration, this was certainly one of the predominant ones. Most of the Polish peasants who came to Texas had owned small farms or worked at the manor's for wages. They lived very simply, went barefooted in the summer and many of their houses had no floors.In 1807, Prussian land reforms ended serfdom in Upper Silesia by royal decree. This granted the peasants greater personal freedom, but it hurt them economically. Peasants had to give back to their former feudal lords between 1/3 and 1/2 of the land that they had held as feudal tenants. This significantly reduced the size of the peasants' landholdings, making it harder for them to support themselves.

The pasants were still required to pay off any indebtedness that they owed for the land they kept. At the same time, the squires who owned the manors were released from all their responsibilities towards the peasants, among these allowing the peasants to graze their livestock on the manor's lands. Since there were no public lands for grazing and the peasants could barely feed their own family from their small farms, feeding livestock became more of a burden than most of them could bear.

In May of 1855, the President of Opole wrote to higher authorities that “one can speak of a steady increase in poverty.” He also wrote that although employment was available for day laborers in agriculture, road building or railways, the salaries for such hard work were insufficient to pay the high prices for food. The following year he reported, "It is not unusual to encounter lean figures who lack the strength and vigor to live." By the spring, he wrote, the peasants had consumed all their stored food and then the starving people "reach for herbs and other unwholesome products."

Social Discrimination: Most of the property in Upper Silesia was owned by German landed gentry, who made up the wealthy elite class from which the peasants were separated both socially and linguistically. All government business was conducted in German, even though most of the common people spoke Polish. This kept the peasants from seeking governmental positions within their counties. Consequently, they were discriminated against, pawns in a German-dominated society. Even newspapers wrote about the "gap between the peasants and the well-off German gentry with whom they were connected by neither religion not language."

A passage in Adolph Bankowski's "My Memoirs," recalled the remarks of a Polish priest in Texas reminding settlers of the conditions they experienced in Upper Silesia provides some insight of what life was like for them in Upper Silesia:

"What freedom did you have in Prussia? Didn't you have to work a great part only for the king? As soon as a boy grew up, they took him to the army, and for the defense of whom and what? Not your kingdom but the Prussian one. You lost your health and lives for what purpose? And taxes? Were they small? Did you forget how you were racked? You talked among yourselves that they took holy pictures from the walls and covers from the beds of the poor. Wherever you went, you had to have a certificate from the officer of the Diet in the village."Conscription: The passage above points to a third motivating factor for immigrating to Texas, namely the desire of many men to evade conscription into the Prussian Army. Service in this rigidly disciplined military body was known throughout Europe for its severity. At the age of 20, every male Prussian subject was compelled to begin a 3-year term of duty in the regular army followed by a two-year term in the active reserves. After this, the men were released into civilian life but were transferred to the inactive reserves, where they remained until the age of 40. During those 15 years, they were required to spend 15 days a year in military exercises and if war broke out, could be called into action. Even after reaching 40 they were not free. Transferred to secondary inactive reserves until age 60, they could be called up in the event of a foreign invasion,

|

|

Economic Downturn: The fourth and probably the most powerful factor motivating the emigration of so many Upper Silesians to Texas was the economic downturn experienced in the 1850s. Because of the Crimean War, which broke out in 1853, the Russian government prohibited the export of Russian grain to European markets, thereby causing high food prices. At the same time, Upper Silesia was hit by a potato blight that caused potatoes, a staple in the Polish diet, to rot in the fields.

Epidemics and Natural Disasters: In the first half of the 1850s, outbreaks or cholera, at times accompanied by typhus, claimed hundreds of victims in Upper Silesia every year. These outbreaks were particularly severe summer and autumn of 1855 when 1,351 lives were lost in this small region. The summer of 1854 also saw a great flood. By early August, unusually heavy rain had filled rivers and streams to overflowing. Then, in the seven days from the 17th to the 24th, non-stop rainfall made the Odra River rise higher than at any other time in over half a century.

All of the five counties mentioned were flooded. In many places houses were inundated up to the windows and even to the roofs, forcing residents to seek shelter in attics or to be rescued by boat. Peasant cottages were destroyed or damaged, roads and bridges were washed away. People stood in water up to their hips with nowhere to go for help. Only half of the early crops had been harvested before the rains had come and the wheat and oats harvest had not yet begun. After the flood, it was impossible to drive wagons into the water-filled fields where the crops lay in the fields rotting. Fearing a winter famine, the desperate peasants trudged through the water to cut and carry out armfuls of wheat and oats . Stored crops become wet and most of them molded badly.

In the summer of 1855, one Opole correspondent wrote that beggars were proliferating on the streets, despite efforts by charitable organizations to help the poor. He described how in Opole "both old and young beggars stand in the doorways asking alms from morning until night, swallowing what potatoes and bread are given to them." He reported that in the preceding 10 years, the poverty of the Upper Silesians had become severe "in contrast to the great wealth of some individuals."

Rise in Crime: Severe poverty lead to an increase in criminal activity. The number of criminals apprehended grew so large that the prisons in Opole could not contain all of them. To alleviate overcrowding, 400 inmates were moved to an old castle in Strzelce. Despite overcrowded conditions, many prisoners felt that the living conditions in prison were better there than in the poverty of the outside world. As one inmate remarked, "Where can we find better conditions than here?"

High Taxes: Yet another economic thorn in the peasants' sides motivating them to emigrate were the high taxes that they had to pay. When the overburdened peasants heard that settlers in Texas did not have to pay any taxes, it was like a dream-come-true. Even a local Prussian official commented in his reports that one reason people were leaving Upper Silesia was to escape increased levees. In 1855, the high sheriff of a Silesian county wrote in a report to his superiors: "The desire for immigration to America has spread like an epidemic disease… I have been flooded with applications for papers allowing emigrants to leave."

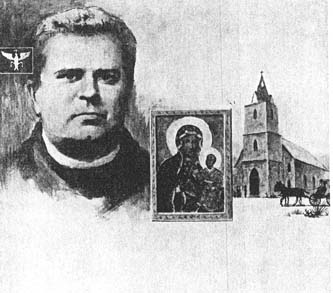

Father Moczygemba

Leopold Moczygemba, who can be properly described as the Founder of Panna Maria, Texas, was born in 1824 in the little village of Pluznica in the County of Strzelce. His father, an innkeeper and a miller, was also named Leopold and, like his son, had been born in Pluznica. His mother, Ewa Krawiec, born in a nearby town, was the daughter of a farmer. The Moczygemba's had ten children. It was customary at the time to have lots of children for two reasons: first, because their chance of survival to adulthood was so low and secondly, to help with the work.

Leopold studied in the schools of Gliwice and Opole. When he decided to become a priest, he traveled to Italy where he received the Franciscan habit in 1843. He was ordained in Italy in 1847 at the age of 22. In 1848, he was transferred for additional studies to southern Germany, Bavaria to be precise, to the motherhouse of the German Conventual Franciscans at Oggersheim

In 1851, Fr. Leopold requested permission to visit with his family in Upper Silesia for 6 to 8 weeks. This would be the first time he would see them in the eight years since he had joined the Order. Permission was granted and he quickly journeyed home. He wrote to his superiors that everyone in the church at Pluznica wept when he offered his first Mass after his return. He also asked for permission to prolong his stay for another month so that he could fill in for the parish priest who was going to "take a cure" at a sanatorium. He added that this would give him an opportunity to practice his native Polish.

Rev. Leopold's parents were so overjoyed at having their son back that they wrote to his superiors asking for their son be given an assignment nearby where they could see him every year. Even after Fr. Leopold returned to Bavaria, his parents continued their efforts to have him assigned closer to them, evidence that they were a very close-knit family.

In 1852, Bishop Jean-Marie Odin of Galveston, Texas - a Frenchman by birth - traveled to Europe seeking priests for his Texas diocese. He visited the Franciscan motherhouse at Oggersheim. There, the Bishop recruited Fr. Keller, and the latter recommended that Fr. Moczygemba accompany them to Texas to do missionary work among the Germans who had settled there. Fr. Leopold, then not quite twenty-eight years old accepted the mission call to America, and having been granted permission to leave for America, sailed with Fr. Keller and two other friars to Galveston, Texas from the French port of Le Havre . Bishop Odin assigned to their care the three main German Catholic parishes (New Braunfels, Fredericksburg and Castroville) as well as missions in 8 other locations in the diocese.For 2 years Fr. Leopold stayed at New Braunfels and then moved to Castroville.

A Win-Win Situation

While living among the German immigrants in Texas, Fr. Leopold saw how successful were their settlements and noted their social and economic advancement in the open society of the Texas frontier. He came to view Texas as the land of opportunity where his own family and friends would be able to experience similar freedoms. For in Texas:- no one had to pay any taxes,

- livestock were allowed to graze freely and there was plenty of grass everywhere,

- people were allowed to own as much land as they could buy,

- their settlement would be composed of all Polish people with no other ethnic groups to discriminate against them,

- the chance of floods was nonexistent on the plateaus

- the weather was much milder than in Upper Silesia

- men were not conscripted into the army,

- he would be close to his family again,

- and with enough land, everyone would have enough food for themselves, as well as enough to sell at the markets.

|

|

Fr. Leopold's letters of this type, as well as later letters sent home by the first group of Polish pioneers, created a sensation in Upper Silesia. They were treated like religious relics - passed from one family to another, and affected whole localities. In fact, Fr. Leopold addressed his letters to whole groups of people. In one letter he wrote "I greet all the people of Boguszyce, Jemielnica and Dolna and everybody."

Emigration Agents

It was the job of emigration agents, who represented German shipping companies, to make the way smooth for travelers going from Silesia to America. They arranged transportation for specific emigrants and for groups of emigrants. They would show up in a village and post a notice on the local tavern door that there would be a meeting regarding emigration. The travel process and costs would be explained at the meeting. People could sign a contract to enlist the emigration agent's services. By 1854, the number of these agents in Prussia had grown so large that the Minister of Commerce, Trade and Public Works found it necessary to issue directives for the regulation of their activities and protection of the emigrants.One emigrant characterized the man who booked his travel as caring for "every person, even for the smallest child." Another said that his agent exchanged all his money honestly and "went with us up to the moment that we embarked on the ship." Not all agents were honest but they did provide a valuable service by arranging for all transportation of travelers from the villages to the railway station, hence to the port of embarkation and aboard the ship that would take them to America.

Many of the peasants had no concept of how far they were traveling or what difficulties they might encounter along the way. All they knew was what they heard from the local gossip: Texas was a land of milk and honey, a land of freedom and opportunity. Even when local officials tried to convince prospective emigrants that they would not succeed in improving their situations by emigrating to America, they replied, "Whether we rot here or there, it's all the same to us. At any rate, we want to try our luck."

Peasants, not Beggars

As a class, the emigrating peasants enjoyed a stable social position in the Silesian community, below the landed gentry yet above the landless laborers. Although hurt by bad harvests, epidemic diseases and flood, they could never be compared with the beggars. They were used to hard work, frightened by the prospect of poverty and very much disturbed by the increasing misery they saw around them. When these landowning peasants began emigrating, an official in Opole wrote to Berlin that "the country is losing its better people - mostly farmers, gardeners and cottagers." A contemporary newspaper called the emigrants looking for a new motherland overseas "the richest portion" of Upper Silesia's Polish population, indicating these were not loose people but rich and settled ones. It added that they were emigrating to Texas not merely for land but for bigger properties. Its can be surmised, therefore, that the Poles who left for America were people of substance. At the same time, the Germans encouraged the Polish peasants to leave because they desired to replace them with German colonists whom they considered to be more efficient workers.The Journey

The first group of Polish immigrants, mostly from the villages of Toszek and Strzelce, sold their properties and left Upper Silesia in late September of 1854. Their departure was chronicled by an article in the German press in Poznan:"On the 26th of September, 150 Poles from Upper Silesia arrived by train in Berlin and on the next day in the afternoon left by the Cologne Railway for Bremen, from where they plan to go by ship to Texas to America. This is worth mentioning because, as is known, Slavic people are so attached to their native land that emigration among them is extraordinary."Though the newspaper mentioned the group as consisting of 150 Poles, historians believe this number refers to families since, in general, wives and children did not count. Accordingly, though the actual size of the group is not know, estimates of its size run from 150 people to 800 individuals.

The farmers and their families boarded a 265-ton wooden sailing bark named Weser. It set sail in October on a 2-month voyage to the Texas coast. For unknown reasons, a handful of Silesians failed to board the Weser and followed a few days later on the brig Antoinette.

On a typical voyage, emigrants spent most of their time in the creaking vessel's gloomy steerage quarters. On eastbound transatlantic trips, this was an area of the ship were cargos of cotton, tobacco, rice and other staples would be stowed. It was a dark, windowless area of the ship near its steering apparatus, whence its name. On the westbound voyage, the steerage was fitted with rough wooden floors and platform-like stiff wooden bunks for transporting emigrants. Every voyager had his or her assigned place, two persons to a bunk, so sleeping quarters were crowded. Each passenger was allowed to bring a mattress stuffed with sea grass or straw, a pillow and a woolen blanket, items sold at the embarkation port. People who died during the voyage were buried at sea. This was the fate of the wife of Joseph Moczygemba, one of Fr. Leopold's four brother.

Meals were served to the passengers as a group. Food consisted of salted pork, salted beef, rice, potatoes, butter, barley, peas, beans, sauerkraut and dried plums. Each day, in the morning and in the evening, the passengers would received coffee or tea, a ship biscuit and drinking water. They were allowed to bring a reasonable amount of food for themselves to supplement that provided. Although the ship's cook prepared the meals, all the passengers were expected to take turns assisting in their preparation.

The price of passage varied with the number of voyagers on each ship. Each passenger received the right to 20 cubic feet of baggage and to store one trunk measuring 36" x 36" x 27". This baggage was stowed for the duration of the trip in the hold of the ship. Passengers could also bring on board a limited amount of hand baggage in the form of small crates that carried items needed during the voyage. Smoking of tobacco was prohibited, as was carrying matches or gunpowder. All firearms were required to be deposited with the captain of the vessel throughout the voyage.

Arrival

When the first Polish immigrants docked in Galveston Harbor on December 3, 1854, no one was there to meet them. So they entered the city where they found white, brown and black people speaking languages foreign to them. They must have been relieved when finally they met up with German-speaking residents with whom some Poles could converse.|

|

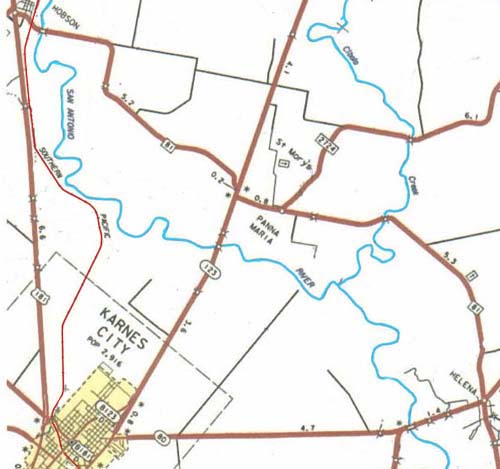

Accounts of their trip on foot to San Antonio by later writers talk of exposure and illness, but none of the peasant's preserved correspondence mentions anything negative about this part of the journey. In fact, one Silesian wrote back home that "there is no winter here." Nevertheless, the trek must have been difficult and upsetting since the man who encouraged them to come had still not shown up. Some of the colonists dropped out, opting to settle in already-established German settlements of Victoria and Yorktown along the way. On December 21st, 159 Poles arrived in San Antonio. Finally, they were met by Fr. Leopold who hastened from Castroville to greet them. He them led most of them back 60 miles to the place he had chosen for their settlement. Fr. Leopold had been busy preparing for the new arrivals, but the settlers arrived sooner than he had expected, and he hadn't made the preparations he had hoped to get ready for them. He had started in 1853 to plan a settlement for them near New Braunfels, where he had bought a parcel of land at a previously planned townsite named Cracow. We don't know why he abandoned those plans. Next, he chose two new locations on opposite sides of San Antonio. One was the already-established American town of Bandera. It was located 45 miles northwest of San Antonio, on the edge of the frontier. The other - which became the town of Panna Maria - was located on an open plateau above the confluence of the San Antonio River and Cibolo Creek in Karnes County. There, upon an open knoll there stood a few clumps of live-oak trees; it was here that the Silesians were told they had arrived at their new home.

Welcome Home?

|

|

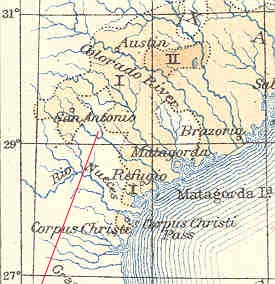

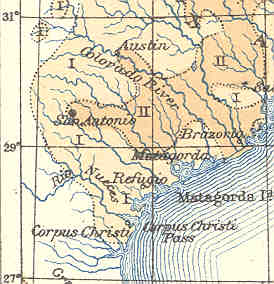

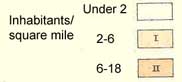

Texas was such a contrast to Poland! The settlers were used to densely-populated towns and villages, farmland that had been cultivated for centuries and regulated forests. The South Plains Region of Texas had at the time a population of less than two persons per square mile. No wonder then that one of Father Moczygemba's brothers, writing the following May to his friends and relatives in Poland, described the area as one where "... one cottage lies from the other ten miles or even more."

The Poles were pleasantly surprised by the warm winter weather in Texas. They came from a cold region known for deep snowfalls. In fact, their homes in Poland were built with steep roofs to prevent the accumulation of deep snow. So the mild winter weather which, according to historians, Texas experienced in 1854 must have seemed like a real blessing.

Getting Started

Lack of food and shelter caused the pioneers discomfort and disappointment. For the first few weeks, that is until they could build temporary makeshift homes for themselves, they were forced to camp under the trees. Some constructed shelters from thin tree branches with thatched roofs made of grass. Others dug a hole into the side of the plateau and covered it with a thatched roof of grass, resembling a lean-to.Here is an account written by a Silesian about those first weeks:

"What we suffered here when we started! We didn't have any houses, nothing but fields. And for shelter, only brush and trees. There was tall grass everywhere, so that if anyone took a few steps, he was lost from sight. Every step of the way you'd meet rattlesnakes. And the crying and complaining of the women and children only made the suffering worse. How golden seemed our Silesia as we looked back in those days."All the known letters from Panna Maria in 1855 contain information about the peasants clearing and working their land. Some letters explained to people in Poland that the land, covered with brush and trees, and had never before been worked. Other letters mentioned that settlers grew corn and vegetables for their own consumption and for the most part raised cattle. One Silesian wrote to his brother that he has 100 acres of land but that he could not sow much because he has only 3 oxen and only one plow.

|

|

|

| Population Density in the South Texas Plains Region 1850-1870 from Statistical Atlas Atlas of the United States 1900, Washington, United States Census Office, 1903 Red diagonal line points to the location of Panna Maria | |

|

|

|

Although working virgin soil required a lot of hard work, the Poles were used to hard work and to difficult conditions. The difficulties they encountered could not have been a "terrible" experience or otherwise they would not have written home, encouraging loved ones to follow in their footsteps. One Silesian wrote to his family in Poland saying "I want eagerly for you to come this year." Another letters explains the predicament the Poles found themselves in - they had money but did not know where to go to get the goods they needed. As one Pole said, "We had money but there was nothing to buy with it."

Another wrote home saying: "Don't wonder that we ask for you to bring so many things, because here there are no people and that's why there are no things." Other Poles were dissatisfied with the quality of American goods and asked family members to bring things like garden tools, a winch, plow blades, wagons, even thread."

Buying Land, Building Homes

The land in this area was owned John Twohig who sold it to the Poles for an exorbitant price of between $5 and $10.80 per acre at a time when the average price of land in Karnes County was $1.81 per acre. To provide land for the less affluent settlers at Panna Maria, Fr. Moczygemba bought a block of 238 acres at $5 per acre and parceled it out to the colonists who could not afford Mr. John Twohig's high prices. However, he reserved 25 acres upon which to build a church.|

|

Homes were modeled after those in Upper Silesia with steep roofs and ventilation openings for the upper floor rooms. The warm Texas weather required modifications which were made later, such as porches facing the south and windows at the rear of the house for cross ventilation. The porch became a storage area for things like saddles, lanterns, rocking chairs, fishing tackle, guns, and flowering plants. They were used for everything in the summer as it was the coolest place of the house - folks did all kinds of work and food preparation on the porches and on hot summer nights even slept there.

The settlers were impressed by the physical distance from one farm to another. One described it by saying "all I can see are clouds and trees." They did not build a village like the ones they were familiar with in Europe. Though there were a few residences near the church that the settlers built in Panna Maria, that was the closest thing there was to a village. Most of the houses were at least 10 miles away from each other.

The horizon was so flat in some areas of Texas that there was nothing in the horizon that people could use as a reference point to indicate what direction they were going in. This was a problem for young children who rode or walked many miles to school. They got to school alright, but had trouble finding their way home in the evening. There are accounts of parents having to go on horseback with lanterns to look for their children and to bring them home.

Texas Poles Say They're Doing Okay

As early as February 1855, the high sheriff of Olesno County in Upper Silesia wrote to his superiors that the reason for emigration from his and adjoining counties were the letters that emigrants that had left the area and were sending back home about their "well-being in America."Four letters sent from Texas in 1855 have been preserved in Opole's archives concerning the activities of emigration agents. One is from, John Moczygemba, an other of Fr. Leopold's brothers. He wrote:

"If you have money, you can keep even 1000 head of cattle, as the Americans do. You can plant cotton, which is very expensive, and I, John Moczygemba, plan to grow it." Of his brother, whose wife died during the voyage to Texas, he wrote: "I talked to Joseph about it and he told me with tears in his eyes that it would be best if you came. When he came, he was alone, but it was not so hard as in Silesia, because here he can breed whatever animals he wants to and it costs nothing."

|

|

That first summer and autumn, the Poles had plenty to eat. Every house had a garden and all vegetables grew well. During the summer, crops of cabbage, lettuce, potatoes and watermelon were bountiful and cheap. In the fall, they gathered nuts from pecan trees that brought families a handsome profit. They were puzzled by sweet potatoes, which they had never seen before. One of the peasant farmers wrote back to Silesia that the settlers were eating well in Texas. He reported that they had bread, fish and coffee on the table every day and - surprisingly - hunting was free. Because many of the settlers were skilled hunters, he wrote, the settlers frequently had wild game, such as deer, turkeys, boars and rabbits.

Wild game was a popular food because it was small enough to be consumed in one day. The hot Texas weather and lack of refrigeration made killing cattle for food unprofitable. When a family butchered a steer, they couldn't keep it for more than a day or two without spoiling, so they were forced to distribute it among neighbors at a very low cost. Salting the beef worked in the cooler months but not in the summer. However, the Poles cut the beef into thin strips and dried these in the sun for later use in cooking. They also avoided meat spoilage by making sausages and smoking them. In traditional Polish-style, a meat smoking room was built within every house.

Raising Livestock in Texas

Livestock were very important to the Poles in Texas, especially oxen which were used to pull carts, plows and move heavy logs. Most Poles raised cattle, which were used for milk, sour cream and farmer's cheese, as well as for meat consumption. The Silesians were thrilled that the cattle could graze on the grass that grew abundantly in Texas and that the herds were allowed to go anywhere they liked! Grazing was not regulated or restricted, as it has been in Upper Silesia. As one colonist wrote: "You don't need to leave anything in the fields for feeding stock because there is very much [grass] for them far and near." Thomas Kozub later recalled the Poles' early cattle raising experiences: After the cattle were branded, they wandered in complete freedom over the vast prairie. Before winter began, the Polish settlers drove the stock into the woods and in the spring they allowed the animals to go where the grass was green. "Under such conditions," Mr Kozub wrote, "we completely lost control of our property. Sometimes we found our cattle with young, but other times we lost them entirely." The vast open prairies of Texas were totally foreign to the Poles, so they found the American way of handling cattle to be very strange. It involved making an excursion over very long distances to round up their animals but eventually the Poles caught on and made those trips rather than lose their livestock.Describing his barnyard in 1855, one Polish farmer wrote: "I bought cows for myself two days ago. A cow costs from $15 to $20 with a calf. I have six cows, five calves and two oxen. [Also] a mule for work and a mare that will foal in two weeks. A mule costs $20 and a mare costs $30, so all my animals cost $198... [In addition] I have ... nine pigs and 90 chickens." Other animals kept by the Poles on their farms were ducks, geese, goats and dogs."

The Second Group of Settlers

The second group of immigrants to Texas set sail from Bremen in three ships in October of 1855. This group consisted of 700 people but they were more financially independent than the first group. The colonists spent 59-days crossing the Atlantic Ocean on the ships Ostend, Weser, and Gessner. The Gessner docked in Galveston, TX, and the other two landed closer, in Indianola. They disembarked with baggage and farm implements, as well as wagons that had been dismantled and crated for the voyage. The pioneers who had wagons reassembled them, packed them tightly and headed westward. Others hired ox-carts or walked. They all went inland on the 175 mile trip to San Antonio, which took them two weeks to complete.In San Antonio, the group was met by a German named John Demner, He told the Poles about desirable land at Martinez Creek 18 miles east of San Antonio. He suggested that they check it out in person, so they formed a committee which was impressed with the location and its fertile land and thirteen families moved there. When they got there, they found one Pole - John Dorstyn - living nearby. He was an exile of the Polish Insurrection of 1830 who had come to Texas in 1835. Over the next decade, Mr. Dorstyn served as an advisor for the Poles in Martinez Creek and assisted them in dealing with American landowners. The land was divided and distributed to the families in tracts of 30 to 40 acres on easy-payment terms. Some of the immigrants settled in the frontier outpost of Bandera. Most, however, came to Panna Maria where they arrived in December of 1855.

By 1856, Fr. Moczygemba had built a hut at Panna Maria for himself. A story is told that when the second wave of settlers arrived, there were great lamentations about the conditions they encountered in Texas. First of all the area where Fr. Moczygemba had decided to establish the town of Panna Maria at the junction of the San Antonio River and Cibolo Creek was overrun with rattlesnakes.. Being unfamiliar with the land, Fr. Moczygemba had no idea that his settlement was intruding on rattlesnake nesting grounds. At least 3 people died from snake bites and everyone carried a hoe or a stick with them at all times to fend of the poisonous snakes. In an effort to appease the new arrivals, Fr. Leopold invited some of them to his hut for dinner. As he was serving the soup, a rattlesnake fell out of the low grassy roof and landed in the center of the dining table. The new pioneers were inconsolable as they scampered out of the hut, screaming in desperation.

|

|

The Third Group of Settlers

In the spring of 1856 about 500 peasants left Prussia for America. They arrived in Texas in late summer and found many things in Panna Maria that the first two groups did not, such as established homes, a church and John Twohig's large stone barn.The settlers paid Mr. Twohig 1/3 of their corn crop to rent his farmland and the barn was used to store his portion of the crop. There was a partition in the barn that formed a room which was set aside as the first Polish school in the U.S.A. Classes were held in Polish and Piotr Kielbasa, who in the late 1800s became the Treasurer of the City of Chicago, was the first teacher. A separate school house was built in 1860 and named St. Joseph's School.

A Time of Hardship

The period from December of 1856 to the end of 1857 were the most trying times for the Polish settlers. A spell of cold wet weather from Christmas in 1856 till late March of 1857, delaying the planting season by a few weeks. By the time the crops were planted and began to mature, a terrible drought begun: no rain fell for 14 months. It was the worst drought to ever hit the state of Texas. Many of the best wells dried up. The earth cracked open a foot wide and 30 to 40 feet deep. All vegetation burned up and disappeared. The land became barren. Cattle roamed far and wide and died looking for water and grass that no longer existed. The price of corn tripled and produce became so expensive that only the rich could buy it.Women walked to San Antonio and other large towns looking for work. Many people left Panna Maria. Some moved to San Antonio where the men worked in mills and women did housework. A large group relocated northward to Franklin County just east of St. Louis in Missouri. Fr. Leopold tried to console the settlers but what they needed was bread, and all he could offer them were prayers. He wrote, "… Were it not for the decency of some Americans in Helena, the first county seat, there would have been few settlers left. There were honest farmers and stockmen whose small wages [to Poles of 50 cents a day] insured the settlers against starvation. John Twohig sent loads of corn, Mr. William Butler, hearing that the people were starving, drove 12 fine steers into the village and made a present of them with the injunction to kill, eat and be merry." The Poles also hunted wild game, which helped to keep them alive through the drought. With the end of the drought, small patches of corn appeared again on the land. Therefore it was with the help of some neighborly Americans that many of the Poles survived.

The great drought not only ruined the settlers' economic aspirations, but it also ruined their relationship with Fr. Moczygemba. In Silesia yet they had been encouraged by the accounts of what a wonderful land of opportunity Texas was. They had been disheartened when, on arrival, they found instead a land of scrub brush, waist-high grass and rattlesnakes. At first they suppressed their discontentment and concentrated on establishing and working their farms. However, the effects of the drought brought their disappointments to the fore.

Moczygemba Runs for His Life

|

|

Except for one or two visits to his family in Texas, Fr. Moczygemba spent the rest of his life serving Polish communities in Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri and New York. He established churches and schools everywhere that he was appointed as pastor and, in Syracuse, New York, the first Franciscan Motherhouse in North American. He was also instrumental in the founding the first Polish American fraternal organization in the U.S.: the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America. He traveled to Rome and received the Pope's permission for the establishment in Detroit of first Polish Seminary in the United States. The Seminary's founder was Father Joseph Dabrowski, who fulfilled Fr. Moczygemba's lifelong dream. Fr. Leopold died on Feb. 23, 1891 in Detroit, where he was buried. In 1974, his remains were reinterred beneath the oak tree in Panna Maria, at the spot where he had celebrated that first Mass.

A Period of Adjustment

The bad conditions in Texas, particularly the Great Drought, and improvements in Silesia brought emigration from Silesia to Texas to a close. Also Silesians became aware of the great discontentment between the northern and southern United States. The possibility loomed that it might result in a Civil War and the Silesians, tired of wars, feared becoming involved. At the same time, the Crimean War had ended and this meant both lower food prices and industrial development in Upper Silesia's coal basin, which created more jobs in the region. Also, beginning in 1856, Silesian harvests improved.With virtually all the Upper Silesian immigrants settled in Texas by early 1857, the next 5 years were a trial - not only of their ability to adapt to the new social and physical environment, but also to their capacity to stick together as a social group. They experienced the trauma of leaving behind all they had known and relocating in a place where the food, climate and people were utterly foreign to them. They could not even make themselves understood to the people around them. It was a task that would try everyone's souls.

|

|

In 1860, Fr. Rossadowski moved to New York, making Fr. Przysiecki the only Polish priest in Texas to minister to all the Silesian communities. He rode from place to place, covering an area over 105 miles in diameter. Loneliness and the stress of his job took its toll on the priest, who was often denounced for his public intoxication. In fact, he was killed in a riding accident in 1863 when he participated in a horse race in an inebriated state and galloped his horse into a low-hanging tree branch, killing him instantly. Fr. Przysiecki's death brought a period of great isolation into the Silesian's lives. People gathered in the churches on Sunday to say the rosary, sing hymns and pray. But with no priest available, a number of Polish Catholics died without the last sacraments and this was considered a disaster in the Polish community.

In late 1866, six Polish priests were sent to America to minister to the Silesian Texans. All of them were warmly welcomed by the Silesian Texans who had been without a Polish-speaking pastor for three years. They were anxious to have their confessions heard and receive the sacraments.

In 1875, the original church was struck by lightening and so damaged that it was about to collapse. It was decided to tear it down, carefully preserving its windows which were incorporated into the new church built on the same spot. The Stations of the Cross from the original church were also saved and are on display at the Polish Museum of America in Chicago. Within one year the construction of the new church was completed. The cross which the original settlers brought from Silesia still stands near the door of the church

The cornerstone for the current church was blessed in 1877. Father Moczygemba was in Texas at the time, visiting relatives, and he was asked to be the guest speaker. The residents of Panna Maria were both surprised and grateful that he was about to attend this historic event. The church was remodeled in 1937.

Other Polish Communities

In 1858, Fr. Moczygemba reported that there were 120 Silesian families in Panna Maria, 50 in San Antonio, 20 in Bandera and 25 in Martinez Creek. Assuming each family had 4.66 members, as calculated for Silesian families enumerated in the US census of 1860, this means the population at these four locations was about 1,000 individuals. Poles also founded the settlements of Cestochowa, Cracow, St. Hedwig, St. Francisville, and Yorktown.In 1867, a census conducted by a Polish priest of the Silesian parishes in Texas and indicated that there were 75 families in Panna Maria, 43 in San Antonio, 12 in Bandera, 34 families in Martinez, as well as 13 families in Yorktown, 14 in Coleto, 13 in Victoria and 12 in Inez.

Bandera: Sixteen Polish families from the second group of immigrants decided to settle in Bandera. Situated in the scenic hill country northwest of San Antonio, it had been established a year earlier by John James. He and another American established a sawmill in Bandera but they were having trouble getting workers to come there because the town was on the fringe of settlement areas and therefore in constant danger of attacks by Indians.

American teamsters working for Mr. James met the Poles in San Antonio and in early February 1855, hauled them and their baggage to Bandera. One American who witnessed their arrival said, "When these Polish people were dumped off here, they had to stay as they had no way to leave." These Silesians went to work at the sawmill, doing manual labor and cutting cypress shingles. Soon they were able to build log and picket houses on land they bought from Mr. James. Over the next 3 years, 4 families from Panna Maria moved to Bandera because they thought it was situated in a healthier location.

San Antonio: A Polish community also sprang up on the southeast side of San Antonio. It was made up mostly of craftsmen whose skills were more in demand in the large town. Within 3 years, Sam Antonio had at least 50 Polish artisan families. They chose Erasmus Andrew Florian as their guide and advisor. He was a political exile from the Polish Insurrection of 1830 who worked in New York and Memphis before moving to San Antonio where he became a successful businessman and banker.

The Civil War

The Civil War began for Texans in February 1861 when the citizens decided overwhelmingly in favor of seceding from the Union. The Poles had not been in the United States long enough to participate in that election, but they learned that all male inhabitants of Texas between the ages of 18 and 50 were liable for military service., except those exempted for occupational reasons. The irony was too much! The Silesians came to the U.S. to escape conscription into Prussian Army and instead, they would end up serving in the Confederate Army! They feared the break-up of their families. Women and children left alone in the frontier to fend for themselves were vulnerable to Indians and outlaws. For these reasons, many Silesians tried to avoid the draft.Union Civil War records were well preserved, therefore we know that many of the Confederate soldiers captured in early 1863 were sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Illinois. Foreign-born men - like the Silesians from Texas - who were not die-hard southerners with heartfelt allegiance to the South were offered the opportunity to swear allegiance to the Union and, instead of rotting in prison, to fight the rest of the war on the Union side. Many of them - at least a dozen - took this option. Records indicate that there were also a few Poles who entered the Union Army directly, and not through being captured.

|

|

Some Silesians served in the Confederate Army but Confederate war records are sketchy, so we don't have written records of their service. We do know that one of the Confederate troops was the Panna Maria Grays. We also know that Alexander Dziuk, a native of the Silesian Village of Pluznica immigrated to Panna Maria with his family and recounted his war years in later life. Here's what he said: "At the age of 18, I was drafted into the Confederate Army and sent to Arkansas. We were badly fed, especially at the beginning and we were armed with old flintlocks. I remained in the Confederate Army until the end of the war and when I got back home, even my own mother did not recognize me." After returning home from the war, he lived to a ripe old age and became one of the wealthiest and most influential farmers at Panna Maria. Most of the Silesians who went to war, returned home to their families.

The Reconstruction Period

The reconstruction period after the war was the most significant time of all for the settlers for it was then that the Silesian Texans were molded into the people they are today.The Civil War ended in early 1865 and for months administration in Texas was nonexistent. Law and order collapsed. The Poles fell victim to robbers, thieves and murderers. Gangs of thieves operated in San Antonio. When one 80-year-old Polish man resisted thieves, they shot him in the arm and side. Another Pole was shot in the head in San Antonio, then robbed of everything - including his coat. Thieves even broke into the state treasury in Austin and stole the last gold the state had left. All slaves were freed . The situation became so bad that federal troops had to occupy Texas to try to re-establish some semblance of order.

In 1867 the U.S. Congress divided the south into 5 military districts, each supervised by a General. New elections were ordered and only union supporters and freed negroes were allowed to vote. White southerners viewed their loss of voting rights - and the enfranchisement of Blacks - as acts of oppression and insult. Post Civil war problems affected all the Silesian communities in the state, particularly because many of the Silesians were accorded voting rights as they had fought on the side of the Union.

The Poles in Karnes County had serious problems due to their Union sympathies during the war. Rev. Bakanowski reported that in Panna Maria, their American neighbors began to make every effort to drive the Poles out of the county, even by force of arms. When they saw a Pole without knowledge of the language, a peasant with no education, being given the right to vote while southerners who were born in Texas were denied the right to vote, they looked upon them as they did upon the Blacks - with disdain and hatred.

|

|

But the harassment did not cease. Cowboys rode into Panna Maria, shooting their guns at the cottages, chasing and roping the Polish children and shooting at the feet of any Poles they met. They rode their horses into the church during Mass and were obscene. Uninvited Americans always showed up armed at Silesian weddings and parties where they harassed and played pranks on the farmers without mercy. A group of men on horseback rode up to a young Polish girl who was milking the family cow. They drew their guns and threatened to kill her on the spot, then decided to shoot the cow instead. They knew the authorities could do nothing to stop them.

The Poles Fight Back

Fr. Bakanowski called his parishioners together to plan a defense strategy during voting registrations. He told them that the church bell would be the alarm signal and he asked the men to join him with their guns and ride to the town of Helena in a show of force. He ordered his cavalry to move as a body and not fire their guns until he gave the order. They galloped back and forth through the town to demonstrate that Poles were capable of defending themselves. The effort gave them a few months of peace.Without a doubt, this moment in the life of the Poles was significant. It was the first time that they stood up for themselves. Through their actions, they were standing up and symbolically declaring to the world: ‘We came a long way to live here and no one is going to force us off our land! We have as much right to live on this land as anyone else does! We are American citizens! Some of us even shed our blood in the American Civil War. This is our home and we are here to stay!"

The Big Show-down

|

|

The townsfolk refused to join the priests in seeking help. They were afraid of retribution - not for themselves so much as for their family members. The two priests living in Panna Maria left the village by themselves, traveling the back road to San Antonio to see the commander of the Union Army in San Antonio. On the way they stopped and asked the bishop to join them. The 3 priests called on the commander, told him what was gong on in Panna Maria and asked for protection. The commander said he's have troops there in a month. One priest replied that "In a month would be too late because during this time they could kill us all." So within just a few days, the commander sent the U.S. Army to Karnes County for the protection of the loyal Polish farmers. The average strength of the garrison was 45 men commanded by 2 or 3 officers. Soldiers were posted as guards in Panna Maria, where they stood at the church door to deter harassment of the Silesians as they attended Mass, filled out naturalization papers, registered to vote or voted. In a matter of months the troops restored law and order in Karnes County.

Yes, the Poles had survived their long and difficult 15-year initiation into the American way of life. But finally, they had become gun-toting, horse-riding, freedom lovers, who stood up for their right to vote and for all their rights as citizens of these United States.

The Story of Panna Maria - Part II: 150 Years of Continuance and Dispersal

Based on a presentation made by Ms. Rosypal to a joint meeting of the Kosciuszko Foundation' Western New York Chapter and the Polish Arts Club of Buffalo. Webpage construcition and maps by Peter K. Gessner.

![]() Return to the main Panna Maria page

Return to the main Panna Maria page ![]() Return to info-poland's home page

Return to info-poland's home page

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |