Władysław Reymont

a keen observer and master of descriptive prose

by Peter K. and Teresa Gessner

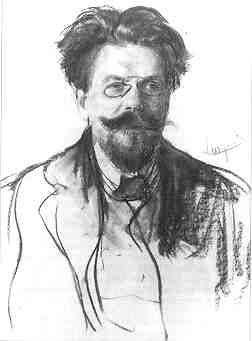

Portrait of Władysław Reymont by Leon Wyczółkowski |

In 1924, Władysław Reymont received the Nobel Prize for Literature for Chłopi (The Peasants) his four volume epic of village life. Of his numerous literary works only Chłopi and Ziemia Obiecana (The Promised Land) have been translated into English. Published in 1924 and 1927 respectively, these translations have long out of print, and in any event failed to do justice to Reymont's literary skill. The Peasants was brought to the screen in 1973 by Jan Rybkowski, but 3 hours and 21 minutes in length it is seldom shown in the United States. Consequently, English-speaking audiences know Reymont primarily from screenings of Andrzej Wajda's screen rendition of The Promised Land which received an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film in 1976.

A Portrait of Łódź

The Promised Land is set at the turn of the last century in the midst of Poland's Industrial Revolution, it presents three young men who join forces to build a textile factory in Polish city of Łódź but whose only common bond is their determination to get rich. Like the Buffalo, NY, of that time, Łódź was then a quickly developing industrial center, attracting labor and entrepreneurs from far and wide. Like Buffalo, it was a veritable ethnic mix of languages, customs, and costumes where workers were underpaid and the factory proprietors lived in ornate palaces. Fortunes could be made, and lost, overnight, and competition was seen as justifying almost every means, in such a milieu, success accrues only to the very determined and the ruthless, and in their different way, the protagonists, themselves representing three different ethnic groups, Karol Borowiecki, a Pole, Moryc Welt, a Jew, and Maks Baum, a German, are willing to be as ruthless as need he. What results is a powerful. dramatic tale.

Marks Baum, Karol Borowiecki, and Moryc Welt as portrayed in The Pormised Land, a film by Wajda |

During his youth, Reymont, the novel's author, run away from his Warsaw home to join, according to the Russian police, the workers striking in Łódź. As a result, he was placed, for a time, under police surveillance. Later on, having decided to write a novel about the teeming industrial town and the people who flocked there in search of work or fortune, lie himself moved and worked there for a period of several months. He detailed his impressions of the city in a letter to a friend, saying that for him it was "a mystical economic power. no matter whether for good or ill, but a power which embraces as it dominates ever wider and wider circles of humanity, devouring peasants, tearing them from the soil and uprooting them, the same for the intellectuals, and the workers, a huge stomach digesting people and land, just a stomach, always hungry."

Reymont had enormous powers of observation: lie was able to immediately perceive and remember in minute detail what was before him. He would bet with his friends that he would observe a street for about 10 seconds and then to describe in detail everything lie managed to remember, which was virtually everything. All this makes the novel a telling document of life in an industrial city at the turn of the last century.

Reymont's Literary Style

In commeting on the literary style of The Promised Land (1899), Frederick Böök, wrote in Essayer Och Kritiker (Stockholm, 1934):

The strange feeling of airlessness that Reymont's novel [Ziemia obiecana (The Promised Land)] so masterfully creates is increased by the total absence of any element of nature. This is something absolutely unbearable. The Polish plains are bare and empty. Łódź is shown in all its terrifying ugliness, with its crowded, dirty streets and smoking factories, with its stigma of chaos and misery, all this in the midst of a nature that has no inspiring or encouraging features. There is nothing more joyless than this gray-black chaos without any greenery or flowers, without any hills or water, without any history or character. Clouds of smoke billow day and night; weaving looms are in motion every Sunday as well as on every Jewish Sabbath; poor-quality, loudly colored fabrics pour in an endless stream all over Russia. This is a city without a holiday, in which Jews and Christians bring their offerings to the Golden Calf; this is the city of Mammon. This is Łódź, the promised land of modern industry.

One can perhaps gain some insight into Reymont's mastery of descriptive prose by reading a recent translation of the opening paragraph of The Promised Land. It is presented on a separate page side by side with the Polish original.

Portrayal of a Polish Village

Reymont wrote The Peasants during the first decade of the twentieth century, at a time, that is, when the massive, over two-million strong immigration of Polish peasants to the United States reached its peak. The novel has special documentary value for those whose ancestors came to the North America during that time: it portrays beautifully, against the backdrop of Polish countryside, the Polish village life with which those ancestors were familiar, detailing its traditions, customs, and folklore.

Reymont structured The Peasants against the cycle of four seasons in order to develop two interrelated parallel plots that of the village of Lipce and that of the peasant Boryna family -- and a multiplicity of subplots in an epic which was recognized as Homeric.

The epic's principal protagonists as portrayed in The Peasants, a film by Rybkowski |

Deep in rural Poland, remote from modern life, and self sufficient economically, Lipce preserved the patriarchal structure, ancient customs, religious rituals, and family structure with all the inherent conflicts existing within the families and the community. The peasant family of Boryna, the wealthiest peasant in Lipce, is seen enacting an ancient human drama of two men, father and son, in love with the same woman, Jagna. She is an embodiment of `eternal womanhood" atid of uncontrollable passion which drives all the coniplications in the family and much of the action in the village. Soon she weds the patriarch Maciej Boryna.

Parallels can he drawn to ancient stories from the classical world. Thus, for instance, to that of Phaedra's love, as described by Euripides. for her stepson, Hippolytus, a love that brings about her destruction. Also, to that of the unlawful passion, described in Book VI of the Iliad, which Bellerophon is suspected of harboring for Anteia, a suspected passion which causes her husband, Proetus. to scheme Bellerophon's destruction. In a tribute to Reymont, the Swedish critic, Frederick Book, an official and influential consultant to the Nobel Prize Committee, wrote "Reading The Peasants, I am subconsciously thinking about Homer. This is an epic talent which chisels monuments Out of scone. Thus far, Poland has had literature describing the lives of the nobility. Reymont complements the history of Polish lifestyles with an epic novel about its peasants."

Set in the partitioned Poland that existed prior to regaining of independence in 1918, the novel describes the hard life of the land-impoverished peasants, unable to sustain their families, it thus presents clearly the reasons so many chose to emigrate. Because Polish land was under occupation, the necessary social reforms and industrial jobs that could alleviate these conditions did not come until Poland regained its sovereignty.

Reymont was the first major Polish writer who chose peasants as chief protagonists of a major novel. He did this at a time when Polish painters. composers, poets and others sought inspiration in the regenerative cycles of nature and in the people near to the soil, Reymont was well qualified to set his novel in a village, for he spent much of his early life in a village where his father was the organist.

The Peasants was the epic for which he was awarded the Nobel prize in 1924. It had been a long time coming. In 1897, Reymont signed a contract with Tygonik Ilustrowany, a weekly, for the publication of the work, but in 1901, looking over the finished manuscript of the one volume work, he decided to slightly alter the first chapter. Growing dissatisfied with what he had written, he tore and partially burned the manuscript. "Please understand -- he wrote to friends -- its a form of torture (...) not to give up but to start writing it afresh. I have either matured or lost my senses. " He continued doggedly in his writing of it, and published the last volume of it in 1909. He was first nominated for the Nobel in 1918. By the time he received the prize he was deathly ill.

On the day after learning he had received the Nobel prize for literature, he wrote a letter to Wojciech Morawski, a New York City newspaper editor he had met when visiting the United States. In the letter, Reymont reflected of the vagaries of fate.

"I am stunned by this unexpected event and by the circumstances surrounding its occurrence, so much so that it seems to he one of life's more bitter ironies. What good is all this to me. I am sick, I just had pneumonia. I walk from room to room with difficulty, I live in seclusion and on a severe diet, 1 have inwardly moved away from the world and its concerns. I dream of silence and the possibility of working calmly as the greatest happiness. Suddenly the great doors of fame have opened before me. Unknown yesterday and disregarded even by my Countrymen, today I have to assume the posture and visage of a famous person. Isn't it laughable. I have suddenly become the pride of my nation! My compatriots are yet ready to read my books. How suddenly, I have become interesting, outstanding, and beloved.

Because of Reymont's health, travel to Stockholm to accept the prize was out of the question. In the autobiography he furnished to the Nobel Foundation he wrote that "in 1922-23 I wrote Bunt (Defiance) and began to have heart trouble. I still have many things to say and desire greatly to make them public, but will death let me?" A little over a year later, Reymont's life came to a predictable end. Just two weeks before, he wrote to Morawski that he was more or less ready for the event. "Death is not terrible," he wrote, "what's terrible is life and the suffering."

| info-poland | Poland in the Classroom | Reymont pages |

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |