Strike!

Adapting to the Industrial Revolution

by Peter K. Gessner

A scene from Wajda's film The Promised Land |

In his autobiographical sketch, Reymont remarks that when he was 20 (hence in 1887), "the Russian authorities expelled me from Warsaw after suspecting me of having taken part in the strike that had then broken out in Lodz for the first time." In 1895, having received a commission from a Warsaw newspaper to write a novel about the idustrial scene in £ód¼, he moved for several months in order to observe first hand the industrial workers and the industrialists in whose factories they worked. He actually wrote The Promised Land while in Paris, but in order to publish a book in the part of Poland under Tsarist rule, the manuscript had to be reviewed by the Russian censors who made him remove from the novel some scenes involving protesting workers and their strike. These scenes were disturbing to the managers and owners of the ód factories who sought to have them suppressed, but no less so to the Russians themselves who were concerned about possible disturbances and uprisings. In the novel, Reymont graphically described the conditons under which the workers strove to earn a living. Those conditions were such as to lead to unrest and strikes, and in the novel and the film version made by Wajda, the final scenes in fact show spillage of blood and deaths resulting from such events.

The workers unrest continued after the 1899 publication of the novel. It reached its zenith historically in 1905. Already, on the January 27, in a reaction to the "Bloody Sunday" massacre of 200 workers in St. Petersburg, 70,000 £ód¼ workers struck, led by the workers of Geyer's factory. The strike spread and by the next day to 100,000 asking for shorter work day and greater compensation.

On February 2, the first spillage of blood occurred. The workers of one of the factories sought to bodily throw out beyond the factory gates a manager who had a reputation for cruelty towards the workers. He managed to have a detachment of the Russian Cossack come to his aid. In the resulting melee, a young worker was killed. The workers pelted the Cossacks with stones and forced a temporary retreat, but then the Cossaks used their rifles. Also an infantry detachment stationed at the factory, attacked the workers from the rear. As they retreated the workers left behind 7 dead and 20 wounded.

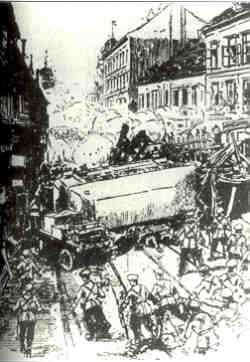

Barricades in £ód¼; A 1905 drawing |

The worst was yet to come. On June 18, the Russian troops fired on crowd of several thousand returning from a manifestation in a suburb of £ód¼. Seven workers were killed. On June 20, twenty thousand participated in a funeral of the victims. The next day, two of the previously wounded, died. A crowed of several thousand searched for, but were unable to find the deceased in the various hospitals. At some point their passage was blocked by Russian infantry and dragoons who opened fire, killing over 30 workers. The next day, the workers begun raising barricades which they continued doing through the night. The battle had been joined in earnest. The Russian authorities threw into it six infantry regiments and four regiments of the cavalry before they reestablished control. All told, some 200 workers died and 800 were wounded.

Nor was this the end of it. On September 30, for instance, two young workers shot and killed the factory owner, Julius Kunitzer, while the latter was returning home by tram. At the ensuing trial, Antoni Szulc, one of the assassins indicated he was not able to stomach Kunitzer's oppression of the workers.

Reymont's novel is particularly noteworthy in that it portrays members of all three ethnic groups - Poles, Jews and Germans - as participating in the no hold barred capitalist struggle to make it big using bribery, chicanery, and exploitation of the workers to amass a fortune. It is less obvious from the book and the film what was the ethnicity of the exploited workers. That information, however, is available. In her excellent book Shtetl, outlining the history of the Jews in Poland, Eva Hoffman provides the information (1) that among the victims of the fighting in £ód¼, 79 were Jews, 55 were Poles and 17 were Germans, that is percentagewise, 52% of the victims were Jewish, 36% were ethnic Poles and 11% were Germans. These percentages differ significantly from those of the contemporary population of Poland as a whole which, according to the 1921 census. According to the latter, 69% of the inhabitants of the Poland were ethnic Poles, with the Jews comprising 8(% and the Germans less than 2%.

It is interesting to consider the reasons for disparity between the population figures and the composition of the £ód¼ work force and why the ethnic Poles had been slow, at the time of the Industrial Revolution, to move into commerce and manufacturing. The landed nobility, or Szlachta, which for centuries had derived its power and prestige from the land, was very much wedded to it and regarded commerce with some disdain. The peasantry, who, for the most part lacked the means to invest in factories and the like, were also very much wedded to the land and continue to be so to this day, a very much greater proportion of the population being involved in cultivating the land than is the case with most developed nations. Accordingly, the field became dominated by Germans and Jews. For centuries, the latter had been forbidden to own land, and, of necessity had made commerce their sphere. Hence, they were much better able to adapt to the demands of the industrial revolution and take advantage of the opportunities it offered, many becoming industrial workers, some owners. Their dominance in industry continued up to the outbreak of World War II, when Jewish firms employed more than 40 percent of Poland's industrial labor force.

[1]Hoffman. Eva: Shtetl: the Lift and Death of a Small Town and tile World of Polish Jews. Houghton Mifflin, Boston 1997.

| info-poland | Poland in the Classroom | Reymont pages |

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |