Henryk Sienkiewicz and Quo Vadis

by Peter K. Gessner

- Origins and Early Life

Influence of Positivist Movement

The Trilogy

A Vast Output

Publication of Quo Vadis

The Story

The Early Christians

Petronius: a Roman Courtier

Origins of Quo Vadis

Award of the Nobel Prize

The Novel's Popularity

Adaptations in Other Media

The Films

|

|

A man of middle height stands at a podium, on a grassy island in the center of Krakowskie Przedmieście, the wide central thoroughfare leading to Warsaw's Old Town. It is December 24, 1898, the centenary of the birth of Poland's foremost bard arid beloved romantic poet whose verses every Pole knows by heart. It is 10 o*clock in the morning and the man at the podium stands in front of the just unveiled monument to Adam Mickiewicz. His face is white like a sheet. He stands silently, facing the twelve thousand specially screened guests and the detachments of mounted Russian Cossack police who have let them past the barricades isolating the street far and wide from the many thousands who would otherwise also he there.

|

|

In front of the guests stand several hundred high school youngsters who, by spending the night in the three churches within the now barricaded area, have fooled the Cossack. Surprised, the latter did not charge when the youngsters marched out of the churches just before the ceremony was to begin. Long minutes pass, but the man at podium continues his silence.

The man at the podium has a speech, but not the Tzar's permission to read it, even though he had personally requested it. Together with Prince Michael Radziwiłł he had headed a committee of illustrious persons of consequence who assembled the funds and obtained the permission of Tzar Nicholas II for the erection of the statue. But though he personally requested permission from the Tsar to read his speech, his request had been denied. And so, on that cold December morning Henryk Sienkiewicz, a Polish patriot to the core, stood at that podium, without a word, for as long as it would have taken him to deliver the speech. That silent vigil was a gesture that everyone present, and all who heard about it. understood perfectly.

As it has happened so often in Polish history, the family roots of this patriot were partly foreign: his father's ancestors were Tartars who had become Polonized and had accepted Christianity (Tartars were traditionally Moslem) in the eighteenth century and had, in the process become members of the lesser szlachta.

Born in 1846. more than half a century after Poland's occupation and partition between Russia, Prussia and Austria, Sienkiewicz died in 1916, two years before Poland's independence was restored. Through the whole length of his life, therefore, Poland existed only as a concept in the mind of Polish people. Sienkiewicz, by creating historical novels that extolled the valiant men and brave deeds of the former Rzeczpospolita, did much to sustain that concept.

|

|

As a university student in Warsaw, Sienkiewicz had witnessed the January Uprising of 1863, the savage way in which it was put down by the Russians, and the massive deportations, with their entire families, of anyone who had taken some part in it to Siberia. It had been the fourth unsuccessful Uprising that the fiercely independent Poles had staged against the partitioning powers. Now, spontaneously, began a national mourning: women dressed in black, spouses exchanged their wedding bands for ones edged with black, and a black mesh was hung in front of the figure of the crucified Christ in Kraków's Wawel cathedral.

|

|

Sienkiewicz joined many of his contemporaries in the judgement that the fiery patriotism of the preceding generation of romantic writers and poets, however genuine and worthy, had inspired the nation to actions which, in the context of nineteenth century's geopolitical realities, brought it no gain, nothing but defeat and deep despair.

The younger generation of writers and artists came to view the new Positivist philosophy as more appropriate to the times. It cultivated rationality, eschewed metaphysical and otherwise uncritical speculation, relied on experience and believed in the progress of science and learning. Its literary output was characterized by clarity of exposition, readability and closure.

The short stories and essays Sienkiewicz began to write fitted these precepts well. So did a series of reports, later published in book form as Listy z podrózy do Ameryki (1880) [Letters from America], that he sent back to Gazeta Polska, a Warsaw daily from the United States, where he remained for three years. He followed these efforts with four Positivist novels: Charcoal Sketches set in a small village deep in the country side (Szkice Węglem, 1877), the moving story of Janko the Musician (Janko Muzykant, 1879), In Search of Sustenance (Za chlebem, 1880) the travails of a family who emigrated to America, and The Lighthouse Keeper (Latarnik, 1882), a brilliant portrait of a Polish expatriate and his many adventures.

In 1883, Sienkiewicz turned, however, to the historical novel. Installments of Ogniem i mieczem [By Fire and Sword], a story woven around the great seventeenth century Cossack revolt, began to appear in the daily Słowo. The novel transported the reader to a time when the Rzeczpospolita was sovereign and mighty, even though beset by many conflicts. The story proved enormously popular with the reading public. Because it was being published in daily installments, the readers could provide Sienkiewicz with almost immediate feedback in the forms of letters. Many sought to influence the development of the story, some passionately imploring him not to harm this or that character.

Sienkiewicz held the opinion that the twin goals of literature should be the uplifting of the human spirit and providing of the readers with what they yearn for. Noting that the public appeared to crave historical novels, he obliged. Ogniem i Mieczem was followed, in 1886, by Potop [The Deluge], a story woven around the Swedish invasion of Poland, and then, in 1888, by Pan Wołodyjowski [Pan Michael], a tale of the wars with the Moslem Ottomans. The trilogy reached virtually every literate Pole and became almost obligatory reading for Polish youth.

Twelve years later, in 1900, Sienkiewicz was to write yet another major novel based on Polish history: Krzyżacy [The Teutonic Knights]. Cast in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century, it both capitalized on, and crystallized the centuries-old torment and distress that the Polish nation suffered because of the aggressiveness and arrogance of its Prussian neighbor.

Sienkiewicz had a way with language, so much so that Polish dictionaries still use many quotations from his works to illustrate word usage. In the trilogy, for instance, he had his characters use Polish language as it was spoken in seventeenth century. In Krzyżacy, he even had his characters speak a variety of medieval Polish which he recreated by utilizing many of the archaic expressions then still common among the highlanders of Podhale.

So prolific a writer was Sienkiewicz that the complete edition of his work runs to 60 volumes. Among them is a very popular children's book W pustyni i w puszczy (1912) [Through Desert and Jungle] describing the adventures of two youngsters in Africa, as well as his best non-historical novel, the 1891 Bez dogmatu [Without Dogma], a psychological study of a decadent fin de siecle figure. Some of Sienkiewicz's work, as for instance Wiry (1910) [Currents] reflect his conservative views and belief in the status quo. Yet these were, as always, conditioned by his patriotism which had him say that: "Any Pole who does not carry in his soul the ideal of independence, is, in some measure, a renegade."

The Polish focus of most of Sienkiewicz's stories might well have resulted in his power as an author remaining largely unknown outside his native lands, had it not been for Quo Vadis, his great epic about Emperor Nero's beautiful but decadent Rome and his persecution of the Christians. Published in installments in three Polish dailies in 1895, it came out in book form in 1896.

The story proved to have universal appeal and it became enormously popular. In France, though in translation, it outsold the works of the most popular French writer, Emil Zola. In England and America it sold 800,000 copies in one year and by 1901, 2 million copies were estimated to have been sold in Poland and Germany alone. In time, it would be translated into more than 50 languages.

In simplest terms, the story, which is set in Rome, is that of two people who meet and fall in love, though not concurrently. Various hurdles and problems keep them apart for much of the novel. She, Kalina, the daughter of the King of the Legians, is a long-term Roman hostage and guarantor that the Legians, a people identified as living between the Oder and the Vistula (i.e. Poland), will not cross the Roman border. He, Vinicius, is a young Roman officer just back from a campaign in Armenia. While he is recovering from an injury in the household of her Roman guardian, they meet and he is smitten by her.

A plot is hatched whereby, through the intercession of Petronius, Vinicius' uncle, the Roman Emperor, Nero, is to transfer the guardianship of Kalina, also known as Ligia, to Vinicius at an imperial banquet. Petronius, like Nero, is a historical figure, described in some detail by the Roman historian, Tacitus. The reputed author of Satiricon, the first novel ever written, the historical Petronius was Nero's confidant and friend whom the Emperor had designated as the arbiter of elegance, that is, the person who had the last word in what was esthetic.

Along the way Ligia, who, unbeknown to Vinicius, Petronius and Nero, is a Christian convert, disappears and the tale now turns into a detective story. With the aid of Chilon, a seedy Greek skeptic philosopher of much wit but low morals, Vinicius manages to track her down but is frustrated in his further designs by Ursus, a bear of a man, her trusted Legian servant and protector. There are several subplots, Vinicius, initially contemptuous of Christianity, meets the apostles Peter and Paul and, eventually, embraces the Christian faith. Meanwhile, Nero, eager to rebuild Rome according to his own design, orders the city be set on fire so as to clear it, then accuses the Christians of the deed and starts a wide ranging persecution of them.

Towards the end of the novel, Sienkiewicz creates a dramatic scene, the symbolism of which would not have been lost on his countrymen: the German beast (a black Germanic bull) to whose horns Ligia (representing Poland) has been tied, is vanquished by Ursus (representing the Polish people), who thereby restores her freedom.

In the novel, Sienkiewicz describes two contrasting communities: One, imperial Rome which dazzles the reader by the excellence of its culture, the richness of its way of life, the extent of its philosophical thought, and the might of its power. The other, Christianity, a moral force which imbues its adherents with both a belief in otherworldly rewards and a strict moral code of conduct based on love, altruism and rectitude. The adherents of the new faith gather secretly, at night, in distant

cemeteries, to listen to the first apostles who bring "glad tidings." Later, they perish in the arenas of the Roman circuses, confident in the happiness that awaits them in "the beyond."

The early Christians are portrayed by Sienkiewicz as people who live in joyous serene communion with each other, who not only worship their God but love Him and each other dearly and long for Him, who believe in non-material rewards and whose faith, untinged with skepticism, has the fervor of new converts. As portrayed in the novel, the interpersonal dynamics of these early Christians remind one, perhaps not inappropriately, more of those seen among adherents of nascent denominations, sects, cults or even communes than of those of members of an established religion.

What material could Sienkiewicz draw on in describing such interpersonal dynamics? Conceivably, on his experiences in a commune he help set up in Anaheim, California. His journey to America had been financed by Count Chłapowski, explicitly so that he would choose a suitable location for a phalanstery, that is, a commune. Having chosen it, he was joined there by Chłapowski, his wife, the famous actress, Helena Modjeska, her son, and others. For a time, they lived together as group holding goods and property in common while planting orange groves. The phalanstery. however, did not prove financially viable and so, after a while, their experiment in communal living was abandoned.

|

|

Sienkiewicz deftly weaves into the historical tableau both Nero and Petronius, the latter becoming a principal protagonist. An epicurean and a skeptic unwilling to make judgments of good or evil, he is nonetheless characterized by an honesty which is both intellectual and daring. He craves excitement and finds it while engaging in pointed verbal repartee with the Emperor. It's an inherently dangerous game, given the respondent is a capricious all-powerful tyrant.

The noted Polish literary historian, Krzyżanowski, claims Petronius "to be the best representation of a courtier to be found in world literature," and suggests that Petronius reveals, as never before or later, the sympathies and weaknesses of the author, which Sienkiewicz usually kept hidden from view. In letters to the woman then closest to him, he admitted as much, writing that he is an aesthete and an artist and the there "dwells" in him "too much of Petronius." To Petronius, life is but an illusion. All that is required is "to know how to differentiate illusions which are delightful from those that are unpleasant," to make use of the former and, in so far as possible, to avoid the latter.

So successful, so multidimensional is the masterly portrayal of Petronius, that some critics claim that the figures in the Christian community seem pale by comparison. Others suggest that Sienkiewicz held back from making the descriptions Christians too multidimensional lest he be perceived as irreverent.

|

|

The title of the book derives from an early Christian legend according to which the apostle Peter, leaving Rome, as the persecution of the Christians surged, was confronted by a vision of Christ. The apostle asked: "Quo vadis, Domine?" meaning "Where are you going, Lord" in Latin, and was told "I am going to Rome to be crucified again," whereupon the apostle retraced his steps returning to Rome where, according to the Christian tradition, he was later crucified.

While visiting Rome, Sienkiewicz became acquainted with the legend. A friend of his, the Polish painter, Henryk Siemiradzki showed him the inscription "Quo Vadis?" on the pediment of a road side chapel. Siemiradzki had settled in Rome and was then famous for his paintings of scenes from the life and history of the ancient Rome. The highly realistic canvases showed the beautiful architecture and the extraordinary pomp of the imperial court. One of Siemiradzki's paintings which Sienkiewicz admired was The Torches of Nero on which the painter had portrayed the martyrdom, in the Neronian Gardens on the slopes of Vatican Hill, of Christians tied to poles and set on fire.

Sienkiewicz was quite fluent in Latin. He had been required to learn the language in high school. After all, for many centuries, down to his time, to be literate meant being able to read and write in Latin. In a 1901 letter he wrote that:

- For many years it has been my habit to read ancient Latin texts. I did this not only because of my love of history, which has always interested me greatly, but also I did not wish to forget Latin. This habit led me to read much Latin prose and poetry without any difficultly and it created ever greater love for the ancient world.

In the same letter he sated hat the idea of writing the novel came to him seven years earlier while visiting Rome and explained it in the following terms:

- I was most drawn to Tacitus as a historian. Dwelling on his Annals I was frequently tempted by the idea of presenting, in a literary form, these two worlds in which one was the all powerful governing machine of the ruling power and the other represented only a moral force. The idea of the victory of the spirit over secular power attracted me as a Pole. Also, as an artist I was drawn to it by the wonderful forms with which the ancient world was able to cloak itself.

Having decided to write the novel, Sienkiewicz - using Tacitus' Annals as a guide - toured Rome and the other locations he was later to describe in Quo Vadis.. He also visited numerous museums and studied extensively the customs of ancient Rome, its religious rites, food, clothing dwellings, jewels, art, tastes, superstitions, entertainment and occupations. As a consequence, historical experts have found virtually no anachronism in the novel.

|

|

Interestingly, Siemiradzki painted a scene very reminiscent of the climactic scene in the novel: a black bull lays slain in a Roman colosseum and next to him is the lifeless form of a woman, her feet still bound to the animal's carcass. The title of the painting is The Christian Dirce, Dirce being the name form Greek mythology of a woman who perished as the result of being tied by her hair to the horns of a wild bull. Siemeradzki's painting, to be found in the National Gallery of Art in Warsaw, is dated 1897, thus it was created three years after Sienkiewicz's visit with the painter.

The reaction of Polish Positivist writers and critics to the works of Sienkiewicz had been that historical novels were an anachronism, that, in writing them, Sienkiewicz had turned away from the Positivist program and serious consideration of societal problems. Such writing, they claimed, amounted to mere entertainment.

A contrary opinion was that of the Royal Swedish Academy which in 1905 awarded Sienkiewicz the Nobel Prize in Literature. The Academy's presentation citation began:

- "Whenever the literature of a people is rich and inexhaustible, the existence of that people is assured, for the flower of civilization cannot grow on barren soil. But in every nation there are some rare geniuses who concentrate in themselves the spirit of the nation; they represent the national character to the world. Although they cherish the memory of the past of that people, they do so only to strengthen its hope for the future. Their inspiration is deeply rooted in the past, but the branches are swayed by the winds of the day. Such a representative of the literature and intellectual culture of a whole people is the man the Swedish Academy has this year awarded the Nobel Prize. He is here and his name is Henryk Sienkiewicz."

After discussing at some length his literary opus, the presentation went on:

- "If one surveys Sienkiewicz's achievement, it appears gigantic and vast, and at every point noble and controlled. As for his epic style, it is of absolute perfection. That epic style with its powerful over-all effect and the relative independence of episodes is distinguished by novel and striking metaphors."

The presentation makes a number of specific comments pertaining to Quo Vadis, to wit:

- "Sienkiewicz discreetly avoids making Nero a major character, but in a few strokes he has portrayed to us the dilettante crowned with all the vanity and folly of his grandeur, all his false exaltation, all his cult of superficial art, void of moral sense, and all his capricious cruelty. The portrait of Petronius, drawn in greater detail, is even better. ... But Quo Vadis contains many other admirable things. Especially beautiful is the episode, lit by the setting sun, in which the apostle Paul goes to his martyrdom repeating to himself the words that he had once written: 'I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course, I have kept my faith' (2 Tim., 4:7).

|

|

History instructs us that, in the confrontation between early Christianity and the Roman civilization, the latter disintegrated and vanished while Christendom became the medieval world's dominant institution. That such should have been the outcome of the confrontation is, on the face of it, astonishing. ln deciding to write about the initial stages of the confrontation, Sienkiewicz set himself the task of describing it in such a manner as to make that outcome credible. The very popularity of the novel indicates that he succeeded. It was considered a masterpiece. It projected an optimism that the fin de siecle public found reassuring. But, such optimism, and, thereby, the popularity of the novel, tends to be affected by world events.

The massive and senseless slaughter on the battlefields of World War I (700,000 fallen at the battle of Verdun alone), not to mention the obscenities of the Nazi death factories during World War II, made that optimism appear unwarranted. It made the descriptions of the moral force of the Christians, confident in their faith, accepting martyrdom serenely, even joyously, seem simplistic and their eventual victory less credible.

More recently, the world has seen the Solidarność movement of the 80's bring about - primarily through moral suasion - the demise of Communist domination in Poland. Its example, moreover, initiated the disintegration and collapse of the whole Soviet Empire. Such events suggest that there are moments in history when a moral force can bring about astonishing change, a fact which renders Sienkiewicz's novel again topical, for the author raises questions regarding moral suasion which are worthy of the readers reflection.

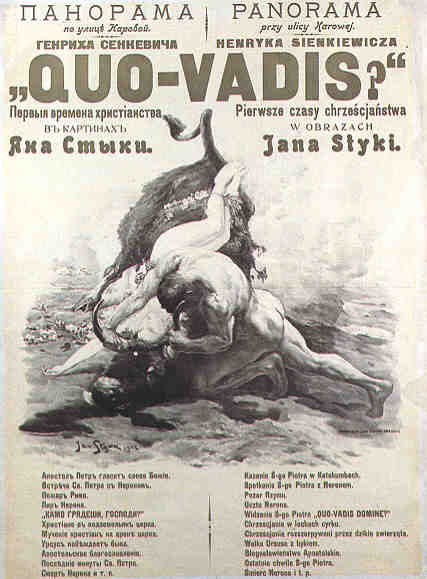

Soon after the publication of Quo Vadis, adaptations began to appear. In 1900, Lwów saw the staging of a dramatic version by A. Walewski with music by Słomkowski. In 1901, a stage version ran for 167 performances in Paris and in the following year, Pathe produced Vadis, a one reeler film version that ran for 12 minutes. During that same year the noted painter, Jan Styka, created a panorama painting which was exhibited first in Warsaw and later in Paris. In 1909, Jean Nogues composed an opera entitled Quo Vadis with a libretto by Henry Cain. It played with enormous success in Paris, then in Nice, and later in Berlin, London, and finally, Vienna, where Sienkiewicz himself saw the 25th performance. In 1909-10, two more stage versions were produced in France, one by Ducis, the other by C. Trioniller Marcuset. In Prague, a stage adaptation by Hoffman met with great acclaim. Five stage adaptations were produced in the United States and one of them was so successful it was taken to London. In 1909, Feliks Nowowiejski wrote an oratorio which met with much success in Germany. In Italy, it was turned into an opera by Marucello.

In 1912, Enrico Guzzoni produced for the Italian film company, Cines, a. nine reel film version which ran for 120 minutes. Up to then, no film longer than two reels (24 minutes running time) had been produced. Thus Quo Vadis (1912) became the first feature film ever. Guzzoni built massive sets that fully expressed the flavor of first century Rome. He provided the film with space and largeness of scale, factor that lent it hither unknown verisimilitude and set a standard for historical spectaculars. He employed 3,000 actors and his staging of the crowd scenes was very smooth

In Paris, the film was shown at the Gaumont Palace, the largest theater in the world at the time. The promoters commissioned from composer Jean Nogues a score to accompany the showing of the film. It called for a 150 voice massed choir. In London, the film sold out Albert Hall which accommodated 20,000 at each showing. In New York City, it had a run of two performances daily for 22 consecutive weeks at the Astor theater where a pipe organ was installed to provide it with musical accompaniment and where patrons paid full theater prices. Twenty-two road companies helped screen the film across the U.S. and Canada. The picture earned $150,000 in America alone. It was shown in premier theaters which were rented for the season. The demand for copies around the world was so great that the Cines Company in Rome was required to keep its staff on a twenty-four hour work shift daily for weeks merely to keep up with the demand. The success of the film was such that it paved the way for the elevation of the cinema to an art form.

A third Quo Vadis film, an Italo German version, was produced in 1924 by Gabriellino D'Annunzio and Gerog Jacoby. It featured Emil Jannings in the role of Nero and a cast of 20,000. Again, the settings, real or artificial, were impressive and the producers went out of their way to make the sight of men and women, torn to shreds and eaten by the lions, realistic.

The 1951 MGM Quo Vadis super-super-colossal Hollywood production directed by Mervyn LeRoy, 171 minutes long, had a cast of 60,000. It featured a beautiful interpretation of Nero by Peter Ustinov who received an Academy Award nomination for it. An extremely expensive film to produce, it generated much preproduction soul-searching about its commercial viability. However, once made it proved so popular as to become exceedingly profitable, second only to Gone with the Wind in the history of the cinema up to that time. Its success led to the production by the Hollywood studios of a whole series of Biblical and semi-Biblical super-colossal films.

Yet another film version of Quo Vadis was produced as a miniseries in 1985 for Italian Television. Starring Klaus Maria Braundauer as a brooding, malevolent but essentially sane Nero, Frederic Forest as Petronius, and Max von Sydow as the apostle Peter, and quite extravagant in its costumes, the film departs quite extensively from the novel's story-line. In the U.S. it is only available in a severely cut down video version.

First published in the October 1997 Bulletin of the Arts Club of Buffalo

| Info-Poland a clearinghouse of information about Poland, Polish Universities, Polish Studies, etc. |