| Book chapters |

Constitutions, Elections and Legislatures of Poland, 1493-1993

By Jacek Jędruch

EJJ Books

Copyright 1998 by Eva Jędruch; All rights reserved.

ISBN: 0-7818-0637-2

|

Chapter Two

|

MONARCHY BECOMES THE FIRST REPUBLIC:

KINGS ELECTED FOR LIFE

|

|

The death of the last male member of the Jagiellonian dynasty marked the beginning of the First Republic. The better part of the period covered here, 1573-1648, was devoted to the development of a truly elective chief executive office. The kings were now kings in name only and in fact became presidents of the Senate elected for life. The candidacy for the office became open to contenders from outside the ruling dynasty, and some 'commoners' later achieved that position. The royal election Seym operated with membership open to all adult members of the gentry who cared to attend. The rules of this direct election of chief executive included some novel features such as the 'pacta conventa' or the covenant between the ruler and the ruled. It constituted in effect a Bill of Rights, including the right to civil disobedience for citizens faced with an executive acting contrary to the Cardinal Laws of the country.

In 1572 Inquisition was banned in Poland, and from 1563 onwards the state ceased to execute sentences imposed by Church courts. During the same period the principle of religious tolerance became law and placed Poland in stark contrast to other European countries torn apart by religious strife. A judiciary system was set up with elective judges, independent of the executive branch, and courts of appeal were established for Poland and Lithuania. The Seyms were elected now on a regular two-year schedule.

In this period the institutions of Jewish self-government made their appearance and developed into a unique system of representation.

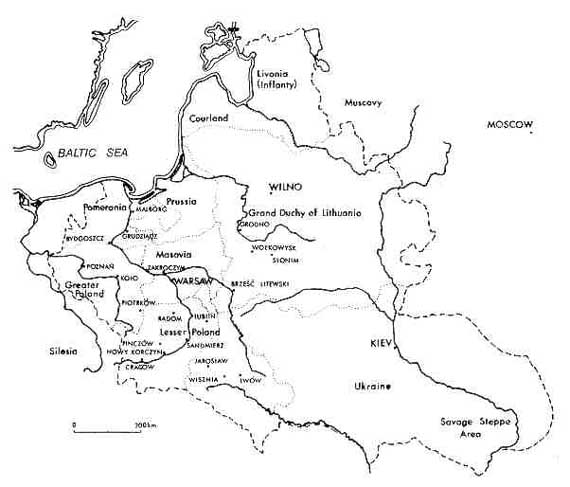

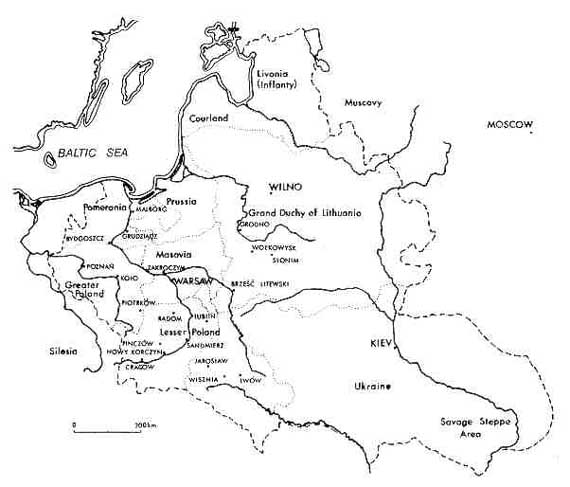

Figure 14 - Meeting places of the Seyms and the General Seymiks in the First Republic, just after the Union of Lublin in 1569. |

SEYMS CLAIM KING-MAKING POWERS

The king-making power of the Seym predates the first session of the bicameral national Seym held in 1493 in Piotrków, and the General Seymik of the province of Lesser Poland should properly be credited with it. This Seymik took the initiative of offering the crown of Poland to Louis of Hungary in 1370, on the death of Casimir the Great, the last male member of the main line of the princely House of Piast. Louis was Casimir's nephew. Thus a precedent was created that the crown is the Seymik's to offer to the candidate of its choice. After Louis of Hungary died without male issue in 1382, the Seymiks of Greater and Lesser Poland offered the crown to Jagiełło, the pagan prince of Lithuania, on the condition that he marry the granddaughter of Casimir and become a Christian. The young lady in question was 24 years his junior, and totally unenchanted by the

prospect. Although this marriage left no surviving issue, the Jagiellonians eventually gave Poland seven kings and the Golden Age of Renaissance. Each of ti'e successive members of that dynasty was required to obtain the explicit consent of the national Seym, by then already well established, before being crowned King of Poland. Thus, a pseudo-election was established in which the senior heir of the preceding king was confirmed by the Seym in a procedure which began to be referred to as the royal election. This historical period is commonly called 'the hereditary monarchy with elective legislature.' It ended with Sigismund II Augustus, the last male member of the House of Jagiełło. His death without issue in 1572 marked the beginning of the era of truly elective kings and the rise of the First Republic. At the same time a political union with Lithuania replaced the former dynastic link.

Inasmuch as the royal election of 1573 was the founding date of the First Republic, it is interesting to note how the event was viewed by the electors themselves. Such insight is provided by the text of the resolution passed by the Confederation of the palatinates of Sandomierz and Cracow on December 17, 1572. The resolution reads as follows:

We, the Senators of the Crown, spiritual and temporal, and the knighthood of the palatinates of Cracow and Sandomierz, having met in Wiślica on the thirteenth day of December, for the purpose of reviewing and providing for the needs of our Common wealth on the occasion of this interregnum, recognize that on the death of our Sovereign it is fit and proper for us to consider our freedoms and liberties, perceiving the basis for them to be in the free election of our King and Lord.

Following the example of our ancestors, and regarding ourselves as their worthy descendants, we pledge ourselves by the good and honest word of knighthood, that we do not wish to depart in any detail from our ancestral custom of electing our Sovereign, as described in our statutes and privileges, which apply to all parts of the Realm equally. Collectively, not excluding any parts of the Realm, neither those belonging to it of old, nor those belonging to it now and so confirmed, we intend to proceed freely and jointly to elect our Sovereign, and also not to allow any part of the Realm, large or small, to separate, but to elect our Sovereign we promise and pledge.

We also strongly warn that, should any part of our Commonwealth want to break away, or separate, and elect a King or a Duke for itself, without consent of all electors, we shall not accept such one as our Sovereign, but will rise against him and his followers in accordance with honor, faith and conscience and persist until they perish or return to unity with us.

To mark our knightly pledge and confirmation, we have caused our seals to be affixed to this act for our own and our descendants' sake, and we have allowed the act so sealed to be entered into the city records.

Written in Wislica on the 17th day of December, Anno Domini 1572.

The main concerns that emerge from this act are the unity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, established in Lublin a mere three years before and the security of the civil rights. The warning, contained in the last paragraph of the resolution, explains why on the election day all electors turned up in full armor and mounted.

Table 15 - Seyms of the Interregnum Periods |

The actual royal election procedure always consisted of three consecutive Seyms, held a few months apart. They were the Convocation Seym, the Election Seym and the Coronation Seym. 15 gives the dates and places where these Seyms were held. The Convocation Seym was invariably called by the senior Senator, the Roman Catholic Primate of Poland and Archbishop of Gniezno, who by law assumed the duties of the King-pro-tempore on the death of the reigning monarch. As the death of a king, or his abdication, was considered a national emergency, the Convocation Seym and the Election Seym were commonly confederated. As such, the decisions made by these Seyms were made by majority vote, and gained the force of law after the election of the king, when approved by him. The Convocation Seym was attended by Deputies elected by the Seymik of each county in the usual manner. It sat in Warsaw and conducted all the preliminary business of the election such as fixing its date, establishing its rules, and reviewing the candidates. The most important part of its business, however, was the preparation of the Articles of Agreement (Pacta Conventa) constituting a Bill of Rights to be sworn to by the Elect. More will be said about them under another heading. The Election Seym followed the Convocation Seym by a few months and usually met at Wola, a small village on the outskirts of Warsaw. Its operating procedures were different from those of ordinary Seyms inasmuch as this was the only occasion when every vote-carrying male could attend a Seym. In consequence, a huge alfresco encampment resulted, much like the Mall rallies in Washington D.C. Although many attempts were made to limit the attendance to Deputies elected by the Seymiks for that purpose, they failed, as no power could bar the electorate from attending.

Fig. 15 - A view of the Royal Election Field at Wola near Warsaw in 1697 when Augustus II Wettin was elected King of Poland. In the First Republic each King was elected for life. A painting by Marco Alessandri (1664-1719) | |

Figure 16 - Bird's eye view of the Royal Election Field at Wola. The voters are shown mounted both inside and outside the enclosure. The shed on the lower foreground housed the Speaker and the election staff. |

After the Speaker of the Election Seym was elected, he was entrusted with police powers and supplied with a staff adequate to maintain order. Among his duties was the layout of the election field. This was a rectangular enclosure separated by a ditch and a fence from the rest of the grounds. A wooden shed was provided at one end to keep the rain off the paperwork and the senior members of the gathering. The rest of the company had to make do as best they could out in the open. The election proceedings took place inside the rectangle, with each palatinate represented by a ten-man delegation, and the delegation voting as a block in the initial proceedings, while the rest of the electors, arranged by palatinate and province, remained outside the stockade. In the mornings, the Senate and the palatinate delegations received in turn the representatives of the various candidates and listened to their speeches extolling the virtues of their man and the advantages of electing him. In the afternoons the palatinate delegations conveyed all of this information to the voters remaining outside the election enclosure. When all candidates were presented and the closing speeches delivered, the voting would start. In the election of 1573 voting alone took four days. All delegations received several large sheets of paper, each sheet bearing the name of one candidate. Each voter was asked to affix his seal to the sheet with the name of his choice. The sheets were then duly collected in the election shed and the total votes added up.

The result was officially proclaimed by the Interrex. The smooth operation of this vast gathering depended much on interaction between the Senators and voters from each palatinate, since it fell to the Senators to provide the assessment of the candidates and guidance in the procedures.Although the attendance at the Election Seyms varied greatly, and was never accurately recorded, a crowd of as little as 10,000 or as many as 100,000 could be expected. The sheer mass of people, horses and carriages must have been overwhelming, and the task of keeping reasonable order among them must have taxe the abilities of the Speaker to the limit. Dust, flies, and horse manure added to the problems. To accommodate this crowd a tent city would be erected outside the confines of the Election Field.

Candidates in the election were barred from Warsaw and its environs, but each could send a representative to the Election Seym, usually with a large retinue, and well supplied with money. Hospitality tents would be set up, and the more influential electors would be lavishly wined and dined at the end of the daily meetings, and quite often bribed on the occasion. This aspect of the election process, one strongly suspects, was what attracted such large crowds to thesc affairs, and often induced people to travel long distances to Warsaw. It was nice tc feel like a king-maker at least once in a lifetime.

The Third Seym of the interregnum period was usually held in Cracow where, after having sworn to uphold all the laws on the books and the Bill of Rights contained in the Pacta Conventa, the elect was duly crowned King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania for life. The ceremony was performed by the Interrex, who at that moment relinquished his powers. Only two kings were crowned in Warsaw instead of, as was usual, in Cracow: Stanislaus Leszczyński and Stanislaus A. Poniatowski. Both eventually abdicated. Much later, in 1829, Nicholas I of Russia was crowned King of Poland also in Warsaw, but was deposed only two years later, leading some people to remark that the choice of Warsaw for a coronation place boded ill for the incoming administration.

Table 16 - Candidates for the Crown Presented to the Election Seyms |

The list of candidates presented to the successive Election Seyms is shown in Table 16. As can be seen from it, the candidacy for the crown of Poland was open not only to the inhabitants of the country but to foreigners as well on the strength of the precedent set with Louis of Hungary and Jagiełło of Lithuania. The offer of the crown to the latter produced a very successful dynasty. Of the eleven elected kings of the First Republic seven were of foreign origin, including two born in Poland. The wisdom of allowing foreigners to be put up as candidates has been questioned at various times. The answer is not a simple one, if only for the reason that the practice seemed to offer several advantages to the electorate at the time. The concept of the 'uniform citizen,' with everyone having the same political rights as everybody else, had not yet evolved, and every politically active group in the country was competing to secure for itself the best possible set of rights and privileges from the ruler. An election of the ruler offered a perfect opportunity for bargaining with the candidates. The candidates were in a far less resistant frame of mind in the matter of making promises and commitments for the future, than a

hereditary ruler would have been on ascending the throne and, furthermore, if the candidate was a foreigner, he was at a disadvantage through the lack of familiarity with people and local conditions. A native would drive a harder bargain. It is obvious that these considerations applied in other countries as well, as for instance is shown by the preference of the English Whigs for William of Orange as a replacement for the exiled native James II. Prospects for foreign alliances also played a part in the considerations. The many intermarriage links between the various ruling houses, foreign and domestic, made the practice of foreign candidature, which seems strange to us now, acceptable then. Successful kingship was an exportable profession in those days.

In time the election procedure had undergone some changes. In the first election the Senators voted with and headed the delegations from their own palatinates. In the second election the gentry felt they were subject to undue influence from the Senators, and insisted on the Senate meeting and voting separately. Both groups, however, insisted on retaining the initiative of proposing candidates and taking the vote first. This led to confusion and on two occasions two different candidates were declared elected: Stephen Bathory by the Seym and Maximilian Habsburg of Austria by the Senate in 1576; similarly, Stanisław Leszczyński and Augustus III Wettin of Saxony were elected simultaneously in 1733 in separate elections held at Praga and Wola outside of Warsaw. In such cases the final verdict was often reached on the battlefield, and the support of foreign armies was helpful, but not necessarily conclusive, as was aptly pointed out by Benjamin Franklin, a

contemporary to the second of these events. In Poor Richards Almanack for September 1748 he wrote:

On the first of this month, Anno 1733, Stanislaus, originally a private gentleman of Poland, was chosen the second time king of that nation. The power of Charles XII of Sweden, caused his first election, that of Louis XV of France, his second. But neither of them could keep him on the throne: for PROVIDENCE, often opposite to the wills of princes, reduc'd him to the condition of a private gentleman again.

Well, not quite private. Stanislaus Leszczyński, as father-in-law of Louis XV of France, lived out his days ruling the Duchy of Lorraine.

Figure 17 - "Hospitality Tents" set up during the Election Seym of 1733 during which Augustus III Wittin was elected King. After a French engraving. | |

Fig. 18 - A scene from the Election Seym of 1764 held at Wola near Warsaw during which Stanisław Poniatowski was elected King. From a painting by Bernardo Belloto called Canaletto (1721-80 |

Irregularities in the royal election procedure did occur and had lasting consequences. Such was the case of the election Seym of 1697, following the death of John Sobieski. During the Seym Senator Michał Radziejowski, serving as the Interrex, pronounced François Louis d'Bourbon Conti the winner in the heated election contest. The chief runner up in this election, Frederick Augustus Wettin, the Elector of Saxony, took advantage of Conti's delay in setting out for Poland from France, and challenged the outcome. Wettin's supporters broke into the treasury in the castle of Wawel in Cracow, secured the regalia, and succeeded in persuading Stanisław Dąbski, Bishop-Senator from Kujawy to crown the challenger, when he arrived in Poland at the head of an army. Conti, who travelled by sea from France, made only a brief landing at Oliva on the Baltic coast near Gdańsk, and hearing of the 'fait accompli' surrendered his claim and returned to France.

The irregular manner in which Augustus II Wettin attained the kingship, by contesting the outcome of the election by force of arms and by overriding the Interrex, started off his administration on the wrong foot, set the public against him, and contributed to an almost complete breakdown of cooperation between the Seym and the 'Elect'. In fact, the whole episode ushered in one of the darkest periods in the history of parliamentarism in Poland.

The forced assumption of power by Wettin could be sustained only by coercion, and unable to sustain it by means of his Saxon troops and local supporters, Augustus finally brought in the Russians. Those who voted in the royal election for Conti retained their pro-French sympathies and were in subsequent decades suitably manipulated by the Bourbon court, adding to the general confusion.

The process of electing kings produced mixed results. Of the foreigners elected, Stephen Bathory of Hungary and Ladislaus IV Vasa of Poland and Sweden were in the opinion of their contemporaries outstanding kings. The performance of Sigismund Ill Vasa is to this day a subject of heated controversy, but with positive reassessment of his administration coming now to the fore. The two Saxon kings, Frederick Augustus II Wettin and his son Augustus Ill, were unqualified disasters. Of the Poles elected only Jan Sobieski made his mark. Like Ulysses S. Grant or

Dwight D. Eisenhower, he was a successful supreme commander elected on the strength of his war record, but in later years his administration ran into political problems with the Seym. Michał K. Wisniowiecki and Stanisław Leszczyński made too fleeting an appearance on the political stage to leave much of a mark. Concerning Stanisław A. Poniatowski, the last Pole to hold the office and the last elective king, the debate still rages. The thirty years of his administration left an imprint of a much more lasting nature than he was ever credited with during his life. Historians are slowly shifting the blame for the collapse of the First Republic to other quarters.

By the early 1700s opposition to elective kingship with a candidacy open to all gained momentum. In 1733 Interrex Theodore Potocki was able to persuade the Convocation Seym of that year to exclude all foreigners from candidacy, while "preserving all other provisions of a free election." This did not prevent Augustus III Wettin to press his claim right then. The new rule was applied after his death and favored Stanisław A. Poniatowski. By this time, however, even the principle of elective kingship came under fire as the cause of foreign meddling in Poland's internal affairs, and the Constitution of 1791 made the crown of Poland hereditary in the Saxon House of Wettin. This was a surprising twist of legislative fancy, considering the disastrous experiences with the two previous Saxon kings. Nevertheless, it was the Saxon Frederick Augustus who ascended the throne of the Duchy of Warsaw with Napoleon's blessing in 1806. He attended the two Seyms held in Warsaw in 1809 and in 1811, abdicated in 1814, and paid for the experience with the loss of half of his native Saxony to Prussia after the defeat of Napoleon.

Throughout the nineteenth century the parts of partitioned Poland remained under suzerainty of three hereditary absolutist monarchies. The Free City of Cracow, which became a Republic, constituted an exception. The Seyms of these provinces, which sat at various times in Warsaw, Poznań and Lwów, lost the constitutional power to elect the chief executives and had to accept the rulers of the partitioning powers, or their deputies. In spite of this, the Seym of the Congress Kingdom attempted the unmaking of a king. When an uprising broke out against the Russians in November of 1830, the Seym supported it and in January of 1831 proclaimed Tsar Nicholas I dethroned as King of Poland. After the collapse of the uprising, Nicholas suppressed and disbanded the Seym and the Senate of the kingdom. In another part of Poland, the Seym of Lwów in Galicia gained in 1873 from the Austrian Emperor the right to appoint the administration of Galicia, but not its chief executive. The Viceroy, usually a Pole, was still appointed by the Austrian Emperor. In the Second and the Third Republic the legislature again gained the power to elect the chief executive.

In appraising the system of electing kings in Poland some foreign assessments point out the most important weakness of that institution. It made it impossible for the neighboring dynasties to marry into Poland's real estate, i.e., the system thwarted dynastic ambitions, just as it was intended to do. In an age of rampant dynastic ambitions, however, this simply invited foreign intervention with the intent of partitioning the country. Thus, an admirable internal political 'development was transformed by external factors into a great impediment to successful foreign policy and national survival, and eventually contributed to the annihilation of the First Republic.

PACTA CONVENTA AND THE ROKOSZ, OR LEGALIZED REBELLION

The formal side of the election of the chief executive developed gradually in Poland during the administrations of successive members of the Jagiełło family. The death without male issue of the last member of that family in 1572 marks the introduction of the Convocation Seym. As mentioned elsewhere, this Seym had the

task of arranging for the election of the next chief executive and of drawing up the "Pacta Conventa," or the "Articles of Agreement" between the candidate and the

electorate. The first Pacta Conventa were drawn up for the election eventually won by Henri Valois, and hence the articles of agreement presented to him became known as the "Henrician Articles." In essence they formed a Bill of Rights. The following obligations bound the successful candidate:

- there will be a free election of his successor

- religious tolerance will be assured in accordance with the provisions of the Confederation of Warsaw

- no additional taxes will be imposed without the consent of the Seym

- no war will be declared nor any called up without the consent of the Senate

- if, during a war, the army is used outside the borders of the Commonwealth, a per diem will be paid to each soldier

- between the sessions of the Seym a committee of 16 Senators will supervise executive actions, one quarter of the Senators to be replaced each half year

- the king will not many without the consent of the Senate

- if any of the above articles are broken by the elect, the electorate is absolved from obedience to him.

The last of these articles became known as the de non praestanda oboedientia article. Together with the first article it led to a number of constitutional conflicts, while its general wording allowed various interpretations. The above articles were considered as part of the "Cardinal Laws" and were reintroduced with minor modifications at each royal election by the Convocation Seym. Usually, a list of specifics was attached to them addressing the situation at hand, such as the financial agreements, foreign treaty obligations, and so forth.

Laudable as the articles were, wiping the slate clean at each election, and writing a new contract between the ruler and the ruled on the lines later advocated by Jean Jacques Rousseau, Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, they had, nevertheless, a destabilizing effect, particularly the reservation clause at the end of the Henrician Articles, which was nothing but an invitation to a legalized rebellion.

In practice, such denial of obedience took the form of a "grand remonstrance," in which the gentry would assemble armed, as if for war, and draw up demands on, or protests against, some action of the executive. If their demands were not met, a civil war started. The demonstration was given the name rokosz from a corruption of the name of the field of Rakos in Hungary, where a similar Hungarian demonstration took place. Rokosz was the supreme sanction which the gentry might invoke against the executive and was extremely damaging to the smooth

functioning of the state. Its threat often paralyzed the executive into complete inaction, even in times of a national emergency.

The first rokosz took place in 1537, still in the period of hereditary monarchy, and lacked the constitutional sanction given to it 35 years later by the reservation clause on the refusal of obedience of the Henrician Articles. It was known as the "Hens' War." It occurred when the gentry, called to arms for war with Turkey, organized a protest against the policies of Sigismund I and the financial operations of his wife, Bona Sforza.

The gentry presented their case in 39 articles, demanding reorganization of the treasury, prohibition of purchases of real estate by the queen, codification of laws, and release from church taxes. The legislation passed during the "Executive Movement," fulfilled those demands.

The first Rokosz carried out under the provisions of the "Henrician Articles" took place in 1587. The Rokosz was started by the supporters of Samuel Zborowski in an effort to rehabilitate him and was directed against Chancellor Jan Zamoyski. In a rival royal election the supporters of Rokosz elected Maximilian, brother of Emperor Rudolf II, to be the King of Poland. The Rokosz ended after the defeat and capture of Maximilian by Zamoyski at Byczyna in 1588.

A bigger rokosz was led by Mikolaj Zebrzydowski, the Senator palatine of Cracow, in 1606, in response to the proposal of Sigismund ifi Vasa that the free election of his successor be abolished and his son Ladislaus be made king (he was elected later anyway). Considering it a gross breach of the first Henrician Article, the participants in the rokosz demanded that Sigismund III be dethroned. The Rokosz was supported by the Protestants demanding better protection of their places of worship. The demands of Rokosz participants, formulated in 67 articles, were rejected by the Seym of 1607; the King's army was dispatched against them, and defeated them at Guzów with a loss of 200 lives. Pacification Seym of 1609 settled the conflict and the Cardinal Laws were reaffirmed by the Seyms of 1608 and 1609.

To resolve the issue whether Zebrzydowski and his supporters were in their rights, a constitution passed by the Seym of 1607 clarified the details of the :procedure and the obligations of the King in the following words:

Should the general law, God forbid, be violated by Our conscious and willful undertaking, or should anyone be oppressed in violation of the law and general free doms, and should this be clearly shown in cause and effect, anyone then will be free to communicate this matter to the Senator of his home constituency, and the said Senator will make the matter known to the Reverend Archbishop of Gniezno in his capacity of Primate. The latter, either by himself, or after consulting with other Senators, must admonish Us, or our successors, and We, whenever such a transgression should occur, will be obligated to correct it.

Should this not take place, the said Reverend Archbishop of Gniezno, acting in concert with other Senators, must repeat the admonition.

If without Just cause either We or our successors do not satisfactorily respond to a matter thus brought up, then all estates should act in accordance with the article de non praestanda oboedientia.

Another important rokosz was led in 1665 by Jerzy Lubomirski, the Grand Marshal of Poland and Field Commander of the Army, during the administration of the second son of Sigismund III, John Casimir Vasa. Here, again, the issue was the attempt to settle ahead of time the question of succession, in particular, the attempts of Queen Louise to promote the election 'vivente rege' of Duc d'Condé. When Lubomirski started a movement of opposition, the King countered by having Lubomirski impeached in absentia by the Seym Tribunal of 1664. When Lubomirski returned from exile and started arming his supporters, John Casimir decided to take the matter to the battlefield, a very unwise move considering the fact that Lubomirski was one of the ablest Generals of the Commonwealth. The King's army was defeated at M4twy in 1666, but the rokosz was finally concluded by negotiation and the submission of Lubomirski.

As can be seen, almost all major rokosz cases dealt with the question of succession, indicating how important the issue of electibility of the Chief Executive appeared to the contemporaries. The person initiating the movement was invariably a high official of the Commonwealth, thus adding weight to the issue. In spite of the elaborate procedure described in the quoted constitution of 1607, this route of checking the actions of the executive tended to be settled on the battlefield. The alternative route, that of impeachment trials by the Tribunal of the Seym, was also available, and was used from time to time. This will be covered in more detail in Chapter VIII.

In retrospect, the use of the threat of civil disobedience as a constitutional safeguard had a severely adverse effect on the political tranquility of the country and at times invited abuse not only by individuals but also by groups of political malcontents. In its operation, the institution of rokosz took the political opposition out of the Seym, where it should have stayed and where its demands would be debated, judged, and possibly legislated on, and drove it out into the country. This encouraged political divisiveness and weakened the State by civil wars.

Legally speaking, the Kosciuszko Insurrection of 1794 could qualify as a rokosz. In this case the citizens questioned the legality of the repeal of the Constitution of 1791 by the Seym of 1793 and the ratification by this Seym of the treaties of the Second Partition and, consequently, refused obedience to the government then in power. This subject will be covered in more detail in a later chapter.

CITIES ELECT REPRESENTATIVES "CIVITATUM NUNTII"

The representation of the towns and the cities in the early Seyms of Poland had a much more irregular history than that of the lands, i.e., the agricultural segment of the population. Its background had not been studied in detail until recent times, although the Seym attendance records of the representatives of the cities of Cracow and Lublin have been published and constitute an exception.

Lublin and Cracow fall into the category of the so-called Royal Towns, legally subject to the state rather than the land jurisdiction. The distinction arose from the origin of the founding charter of a town. Cities and towns founded by the King remained under the King's jurisdiction, were subject to separate laws, and had judges appointed by the King. Such cities generally were subject to a flat tax rate. When extra taxes or legislation involving the towns was on the agenda of the Seym, the King would send the writs of Summons to them as well as to the lands. Knowing that their delegations were invariably forced into accepting higher tax levy, the cities and towns were reluctant to respond to the summons and often would choose to accept a flat tax rate and no representation. This situation is well described by a quote from the instruction sent in 1503 to the Senate by King Alexander in connection with the forthcoming Seym in

Piotrków:

For participation in the debate on all matters, in particular the defense of the Realm, the representatives of Lublin, Lwów and other cities should be summoned. His Majesty is of the opinion that they should be summoned to the current Seym and he will consent to issuing a Writ of Summons. Prior to His Majesty's arrival, he wishes you to decide to which towns it should be addressed, and which towns should be summoned. This is to assure that whatever you decide regarding the defense, the towns will not excuse themselves and refuse to carry the burdens, which they should share together with all the lands of the Kingdom for the needs of the Realm.

The cities and the towns were accordingly invited to this Seym.

Table 17 - Seym Attendance of Representatives of Lublin |

The procedure for electing the representatives of the cities differed from that of the lands. It is spelled out in the records of the Seym of Piotrków of 1565 with regard to the city of Lublin. The city councillors were directed, whenever the need arose, to send Deputies to the Seym. First, they were to call up five spokesmen from the city population at large, according to the ancient custom, then, with their consent, elect the Seym Deputies. The Deputies were to be given the postulates of both the City Council and the population at large, and were to be sent to the Seym at the expense of the City. We see, therefore, that at least in Lublin the election of the Deputies to the Seym was indirect. Table 17 summarizes the attendance record of the representation

of Lublin at the Seyms of the hereditary kingdom and the First Republic. The attendance was sporadic, but not negligible. Lublin was a well-established, medium-size city, and its attendance record is probably representative of other cities as well.

The Pomeranian cities of Toruń, Elbląg and Gdańsk sent their representatives to the General Seymik of Prussia and through it participated until 1772 in the election of the Deputies to the Seym. In 1569 the city of Wilno gained the right to send Deputies to the Seym but, like other cities, used it only sporadically.

In comparison with other cities in Poland, Cracow held a position apart on the strength of a privilege given to it by Prince Leszek the Black (1279-1288), who incorporated the burghers of that city with the knighthood of the palatinate in recognition of their services in the defense of the castle of Cracow during a contest for the throne. It entitled Cracow to send its representatives to the Seymik of Proszowice, and to the General Seymik held at Korczyn. This favored position was reconfirmed in 1505 by a privilege given by Alexander I, and again by John Casimir Vasa's Coronation Act of 1649. The summons to the city were by a separate Royal Writ until the middle of the 1500s; thereafter, they were included in the standard Universal Proclamation. Although theoretically given the same rights as the Deputies from the lands, the representatives from Cracow were reluctant to use them to their full extent, and from 1565 onwards were limited to debates and votes on matters concerning the cities only.

Generally speaking, the cities had a tenuous hold on participation in the Seyms and, limited as it was, it faced a stiff opposition from the gentry, jealous of their position. The Seym of Radom of 1505 introduced an era of open challenge on the part of the gentry to the rights of the cities to send Deputies to the Seyms, and by 1518 the Deputies of the gentry demanded of the King that the Deputies from Cracow be removed from the Seym chamber. In 1537 they were forcibly ejected, and in 1539 an attempt was made to bar their entry. In 1569, during the administration of Sigismund II Augustus, Deputy M. Sienicki, leader of the liberal opposition, made a statement that he did not wish to speak in the Seym while the Deputies from Cracow were present. In spite of all these difficulties the Deputies from Cracow participated in the debates of the Seyms of 1562, 1587, 1589, and 1634. However, the general tendency of the Deputies from Cracow and other cities was to maintain a low profile. They often opted for having their proposals presented by one of the Senators. This had the adverse effect of creating the impression among other Deputies that the city Deputies had no right to speak, in spite of the repeated reassertion of this right by several kings. Sebastian Petrycy, a keen political observer, ridiculed the burghers by saying: "people from some cities attend the Seym, but sit apart, listening to the ready-made speeches." Usually the city of Cracow sent two Deputies, called Ablegates, who were commonly elected from among the members of the City Council by the Council itself, although in 1552 the population of the city elected

two additional observers to oversee and report on the activities of the two Ablegates. The better known Ablegates of Cracow in 1575 were A. Beiza and Andrew Petricovius, Doctor of Canon and Civil Law.

The Swedish invasions (1655 and 1702) and the devastation of war contributed much to the decline of the cities in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. With it came the reluctance to send representation to the Seyms, and the absence from the Seyms meant further reduction in the political influence of cities. The lowest point was reached in 1765 when the Seym struck the cities from the Estates of the Commonwealth to be represented in the Seyms with a right to vote. However, only three years later in 1768, these rights were restored to Cracow, Gdańsk and Toruń, the three largest cities in the Conimonwealth. By then the cities were recovering from the economic decline and were staging a political comeback. The highlight of that comeback occurred in 1789, when the representatives of 140 cities and towns assembled in Warsaw and participated in the "Black Procession" to the Seym, demanding restoration of full rights of representation. Although their demands were only partially fulfilled at the time, the movement they set in motion was unstoppable, as will be seen later.

PERIPATETIC SEYM AND THE PLACES WHERE IT MET

The process of reunification of Poland from the dynastic subdivisions of the Middle Ages, and the growth of the state through political unions, led to the gradual shift of the political center of gravity of the country. The choice of the meeting place of the national Seym followed these trends. In addition, there arose occasionally political situations which made it advisable to hold a Seym close to the scene of action. In such cases, particularly in the period of the hereditary monarchy, Seyms were held in other than customary places.

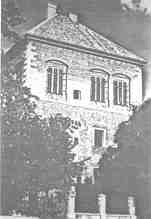

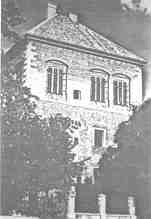

Fig. 19 - The keep in the castle or Piotrków. Until 1567 most of the Seyms of the hereditary monarchy convened here, while their membership rose from 54 to 92 Deputies. Shown in the present day condition, it now houses a regional museum. | |

Figure 20 - The castle of Craców, where 29 Seyms were held including 11 of the Coronation Seyms. |

As the national Seym gained in stature and membership, it moved to more elaborate quarters. While the county and palatinate Seymiks met as a rule in parish churches, the national Seym enjoyed the hospitality of the King, and met generally in one of the royal castles, using at first such accommodations as were available. In time, however, it became a practice to set aside special quarters in each of the castles used as the meeting places of the Seym. In later years of the existence of the First Republic, when the Seym became a dominant political institution of the country, its position justified the major reconstruction of its seat to accommodate its needs. However, when the national Seym started to meet in Piotrków in 1468, all this was still in the distant future, and the first Seyms met within the confines of the castle of Piotrków in very modest surroundings indeed. Of the castle buildings, the most important still survives and is used now as a regional museum. Though originally higher and crowned by a Polish Renaissance attic, i.e., a decorative wall concealing an inverted,

funnel-shaped roof, its present height is lower, as it was burned down during the Swedish invasion in 1657 and reconstructed in 1670 with a conventional roof. This is the form in which it survives until the present day. In 1578 the Tribunal of the Crown (Supreme Court of Poland) was also established at Piotrków which was, at the time, renamed Piotrków Trybunalski. The sessions of the Tribunal, lasting six months each, were held there for 214 years.

Fig. 21 - A view of the Chamber of Deputies in the Castle of Craców. The coffered ceiling features life-size head carvings of various personages from the 1550s. When the Seym was in session here, more elaborate seating arrangements were provided. | |

Figure 22 - A view of the Senate Chamber in the castle of Craców. A gallery wisible at the far wall provided for the visitors. The Chamber is shown in its present day condition. During a session of the Senate appropriate seating arrangements were provided. |

After Piotrków, the castle of Cracow shared the distinction as one of the seats of the early Seyms. No less than 29 Seyms were held there, and even after Warsaw became a regular seat of the Seym, Seyms continued to be convened in Cracow occasionally until 1734. The most important of these were the Coronation Seyms, conducted with much pomp and ceremony. The Coronation Seyms continued into the era of elective Kings, even though those were really Presidents elected for life rather than true monarchs. The parliamentary quarters of the castle consist of the Hall of the Deputies, also known as "the Hall under the Heads," and of the Senate Chamber. The first of these has a magnificently carved and coffered ceiling, containing 30 life-size heads of men and women dating back to the 1500s, and a wall frieze painted by Hans Durer.* The Senate Chamber is decorated with splendid tapestries ordered by Sigismund Augustus (1520-1572) and contains a small gallery for the public. The cathedral of

Cracow, also on the castle hill, was the scene of the actual coronations and contains the tombs of the Kings, both hereditary and elective. Traditionally, the crown jewels were kept in Cracow.

Table 18 - Geography of Sessions of the Seym |

After the Union with Lithuania in 1569 and the rise of the First Republic, the meeting place of the Seyms was moved to Warsaw to shorten the travel distance for the Lithuanian Deputies. Except for 11 Seyms held in Grodno and an occasional Seym held elsewhere, Warsaw had become the Seym City, hosting 148 Seyms. This tradition was carried into the Duchy of Warsaw and the Congress Kingdom of Poland of the Partition period when two and four Seyms were held there, respectively, and was continued in the Second and the Third Republics, as noted in Table 18.

The Seyms held in Warsaw used the premises set aside for them in the Castle of Warsaw. They were constructed during the administration of Sigismund Augustus according to plans drawn up by Giovanni Battista Quadro (?-1590). The "Hall of Three Pillars" that he created for the Chamber of Deputies is in the form of a spacious hail It was divided into two aisles by a row of pillars, sup porting a vaulted ceiling. On the south side the hall opened into the interior of the Town Tower. From there, a spiral staircase connected it with the Senate Chamber, located on the floor above. "The Hall of One Pillar" adjoined the Chamber of Deputies and was used for its offices. The physical placement of the Senate on the floor directly above the Seym corresponded initially to the dominating political position of the Senate at the time, and the terms the Upper and the Lower Chamber were synonymous with the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies. Both, the physical and the political position of the two chambers, were to change in due time.

Fig. 23 - The Castle of Warsaw, the seat of most of the Seyms of the First Republic as well as some of those of the Partition Period. The new Seym and Senate Chambers were located to the right and the left of the tower, respectively. Shown after reconstruction from the damage of World War II. | |

Figure 24 - Joint session of the Seym and the Senate in the old Senate Chamber of the Castle of Warsaw. The empty chairs in the forground belong to the Ministers, shown here standing at the far end on both sides of the King, as was customary, during the speech from the throne. From a seventeenth century English copperplate |

These parliamentary premises witnessed the passage of many important constitutions, such as the Henrician Articles, the first Bill of Rights as it were, and the signing of the Act of Confederation of Warsaw, both in 1573, by which the signatories undertook to maintain the freedom of religious belief and accepted the proposal of Deputies from Sandomierz to ban the coercion of peasants in religious matters.

The cramped quarters of the Senate did not allow visitors to attend its sessions, except by special arrangement. Jan Chryzostom Pasek (1636-1701), a gentleman-soldier, left us, in his colorful diary for 1666, the following description of how one could obtain admission:

When the Deputies move to the second floor, where the sessions are held sometimes [jointly with the Senate], and the call is given:'Whoever is not a Deputy, please withdraw, one should try to make acquaintance with the Speaker, as I did and thus use the influence of important people to avoid being ousted from the chamber, by explaining: I came to drink of knowledge in this school, I'll reveal no secrets!' The Speaker would say: 'Very well, I commend your noble inclinations.' So when they chased others out of the Chamber, I simply nodded to the Speaker, while others crammed

headlong through the door, some getting swatted on their backs with the Speaker's staff; then did my companions wonder: 'What luck you have! I hid myself behind the tile stove, yet was forced to leave, while you sat through the session.' They did not know I'd cajoled the Speaker into it.'

At the start of the administration of John Sobieski, in the years 1678-1681, new quarters were constructed in the west wing of the castle of Warsaw for the Chamber of Deputies. At first it consisted of a spacious one-story hall, with benches for the Deputies placed in a horse-shoe arrangement of several rows, backed by additional space on the outside for observers and visitors. Subsequently, this arrangement had to be modified as a result of a męlée between the spectators and the Deputies which took place in 1762 and in which "swords and pistols were drawn." Enraged by this attempt at intimidation of the Deputies, the Seym stopped its activity and disbanded without passing any legislation. To prevent further threats to the Deputies, the Senate, acting in the capacity of custodian of the parliamentary quarters, decided to increase the elevation of the Chamber of Deputies to two stories and to equip it with a gallery for visitors on the model of the Senate Chamber. The gallery running around these walls, was entered through a staircase located along the fourth wall, and accessible from outside of the Chamber of Deputies only. The architect chosen for the design of the new chamber interior was Jakub Fontana (1710-1773); the alteration was completed by 1764, in time for the Convocation Seym of that year. The separation of the visitors proved to be quite effective and there has not been any further attempt from the gallery on the life or limb of a Deputy since. In all fairness, however, one must observe that the range and accuracy of fire arms was quite limited in those days. This feeling of security due to extra dis tance is no longer true in our days, as witness the events on the gallery of the U.S. Chamber of Representatives in the Capitol in 1954, when five Congressmen were shot from the visitors' gallery by Puerto Rican nationalists.

Fig. 25 - Old Chamber of Deputies in the Hall of Three Pillars in the east wing of the Castle of Warsaw. When the Seym was in session here, proper seating arrangements were provided. The Seym sat here from 1570 to 1681, when the Chamber of Deputies was moved to the west wing of the Castle | |

Figure 26 - The interior of the new Senate Chamber in the Castle of Warsaw. In the First Republic, the elected king served as the President of the Senate. The galleries for the public are visible on both sides. |

The relocation of the Senate to the same wing followed in the administration of Augustus III Wettin, in the years 1737-1746. Now, both chambers were

located on the same level, were made more roomy, and incorporated galleries for visitors. The Senate Chamber was larger and more elaborate of the two, as it was intended to accommodate the joint sessions of the Seym and the Senate, held as a rule for several days at the beginning and the end of each legislative period.

The well-known Swiss mathematician, Johann Bernoulli (1742-1807), who visited Warsaw in 1778, left us a detailed description of both Legislative Chambers. The Senate Chamber contained:

four rows of benches covered with red cloth, arranged in an amphitheatre. Before the first row there stand 60 chairs covered with red velvet, intended for Senators. At the end of the Chamber stands the Royal throne, covered also with red velvet, with gold trim. It is an armchair placed on an elevation and under a canopy. The first two rows of benches are intended for Deputies, the next two for the more prominent visitors. The two longer walls contain galleries for gentlemen visitors. Lady visitors sit even higher, in rooms placed opposite the throne, which afford a view from above through the windows.

It was in this chamber that the joint session of the Seym and the Senate took place on May 3, 1791 during which the new Constitution of the country was adopted. For this reason the chamber has for the Poles the same emotional value as the Independence Hall in Philadelphia has for the Americans.

Bernoulli describes the Seym Chamber as:

decorated with frescoes, and around it are placed the galleries for the visitors, equipped with benches and supported by columns in the shape of palm trees. These bear the coats-of-arms of the palatinates. Part of the gallery above the entrance is enlarged, so that it accommodates several rows of benches. In the Chamber itself, there are wooden benches painted gray, without covering.

This chamber offered much improvement, both as regards space, lighting, and provisions for visitors, over the old Chamber of Deputies in the "Hall of Three Pillars" in the east side of the castle. In the new quarters, the Seym debates on controversial issues attracted many spectators, who often spilled over from the overcrowded galleries onto the ground floor and stood in the aisles, or took up vacant seats intended for the legislators. Attempts to drive them out often proved ineffective, particularly when directed at the ladies, who took a lively interest in the proceedings and cheered on the more popular debaters.

Besides Warsaw, some Seyms were held in Grodno, a small town in Lithuania close to the border with Poland, a site chosen following the precedent of Piotrków, located in the same relation to Greater and Lesser Poland. A constitution of 1673 specified that every third Seym should be convened in Grodno; however, the Senate which made the actual arrangements did not follow this prescription too closely, and only 11 Seyms were held there. A building of the Castle of Grodno was used on these occasions. As it happened, the last Seym of the First Republic in 1793 took place there, and two years later the

Castle of Grodno was also the witness of the last official act of the First

Republic, the abdication of Stanisław August Poniatowski from the kingship of

Poland.

In Warsaw, the former parliamentary quarters in the Castle of Warsaw were demolished in the late 1830s on the orders of Emperor Nicholas I as an act of vengeance for the act of his dethronement passed by the Seym in 1831. At that time, the space occupied in the castle by each of the two chambers was divided by an addition of a floor and partitioned into small rooms. With the reunification of Poland in 1918 the former chambers in the castle could not be quickly restored to a useable condition. The Seym selected instead the former property of the Institute of the Gentry in Warsaw, which had been subsequently used as the Alexander and Mary Academy for Young Ladies, and ordered its adaptation to the needs of the Seym. The former chapel of the Academy became the meeting chamber of the Seym. Since the 1970s, the old chambers in the Castle of Warsaw were restored to their original form to become a historical landmark and museum.

THE SENATE AS "GUARDIANS OF THE LAW"

In the course of the fifteenth century a two-house legislative structure developed in Poland, consisting of an elective House of Deputies and an appointive Senate. The entire membership of the Senate held their seats on the strength of the office to which they were appointed outside of the legislature, either in the Church or in the administration. These offices were generally held for life, and the appointments to them were made by the King. In 1589 the Kings of Poland received from Pope Sixtus V the right to appoint bishops from a list of candidates submitted by the cathedral chapters and with the Pope's final approval. In addition to all the Roman Catholic bishops the Senate included provincial administrators, that is, palatines and castellans, with the latter subdivided into two grades: the major, and the minor. Sometimes minor castellans were not summoned to the sessions of the Senate and on these occasions they were allowed to run for Deputy to the Seym and, if elected, could also be chosen Speaker of the Seym. No minor castellans were ever appointed in Lithuania.

Table 19 - Major Senatorial Families of Poland and Lithuania | |

Table 20 - Composition of Senate with Appointive Membership |

The members of the Senate almost invariably came from a small number of "Senatorial Families," and were aristocrats in substance, if not in title. The principal of these families are listed in Table 19. Thus, the Senate bore a close resemblance to the British House of Lords but with the membership entirely composed of "Life Peers." The number of Senators varied with the geographic

extent of the country at a given period. Before the union with Lithuania in 1569,

it consisted of 11 bishops and archbishops, 19 palatines and 19 castellans plus 5

ministers, 54 persons in all, each appointed by the King. Later changes in

membership are shown in Table 20.

The composition of the Senate, given in this table, represents the theoretical maxima which could be achieved if none of the palatines, castellans or bishops were appointed Ministers. In practice, the Chancellor was invariably a bishop, and a sizable proportion of the ministerial chairs were filled by palatines and castellans. The number of Ministers with a seat in the Senate kept increasing with time and the early positions of Chancellor (foreign and internal affairs), Grand Marshal (Lord High Justice), Treasurer, and Vice Chancellor were later supplemented with other Ministers, as is also shown in Table 20. The step increases in the composition of the Senate took place after the reunion of Pomerania with Poland in 1466 when senatorial seats for Royal Prussia were created, and after the reunion with Masovia in 1529. The biggest increase took place in 1569 after the union with Lithuania, when the number of ministers was doubled and the Lithuanian bishops, palatines and castellans were invited to sit in the enlarged Senate as well. No minor castellans were appointed from Lithuania, possibly due to the much lower urbanization of that province as compared to Poland.

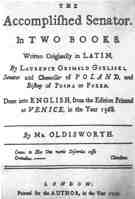

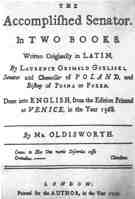

A legislative career in the Senate usually started in the lower chamber. The first step was to run for Deputy to the Seym. If then a successful Deputy was elected Speaker of the House, his further career in the administration was assured and an appointment to a senatorial position frequently followed. The senatorial positions, in turn, had a definite graduation, starting from a minor castellan in a provincial town and ending in a ministerial position of the national government. Talented individuals usually passed through a sequence of these positions. Although each appointment was for life, resignation and reappointment were the rule. This selection process brought many outstanding individuals into public life. Scholars, administrators, soldiers, and occasionally a major political thinker, graced the Senate roster. One such outstanding thinker, whose influence left an imprint both at home and abroad, was Senator Wawrzyniec Goślicki (1530-1607) better known abroad under a Latinized form

of his name, Laurentius Grimaldus Goslicius. William Shakespeare, a contemporary of Goślicki, modeled on him the figure of Polonius, Lord Chamberlain of Denmark in Hamlet, creating a figure of garrulous disposition but worldly wisdom. Goslicki's distinguished career in politics and diplomacy was supplemented by original writing, the best known work being a treatise on political theory De optimo senatore libri duo, originally printed in Venice in 1568, and reprinted in Basel in 1593. It has as its main theme the idea that "in the private happiness of the subjects consists the general and publick happiness of the commonwealth," and the principle that laws must be greater than any individual, including the King. The book intensely opposes the "divine rights of Kings," and this probably accounts for its popularity in England. Three English translations of De optimo senatore were published: The Councellor exactly protraited in two books (1598), A Commonwealth of good Counsaile (1607) published with the section on the rights of kings deleted, and finally, The Accomplished Senator in two books (1733). The ideas contained in the book were considered dangerous enough to cause the suppression of each successive translation in England. Nevertheless, to judge by quotations from it appearing in several English political pamphlets in the 1600s, enough copies survived to fuel the agitation against the arbitrary rule by the Stuarts. The book's influence surfaced again in the American Declaration of Independence, where some phrases and ideas bore a striking resemblance to Goslicki's formulations.

Fig. 27 - Stanisław Krasiński (1585-1649). Elected Speaker of the General Seymik of Masovia in 1633, 1635, Chief Justice of Crown Tribunal in 1633, Deputy of the Seyms of 1634, 1635, and 1638. Appointed Senator in 1641. A portrait by Daniel Schultz (1615-1683). | |

Figure 28 - Title page of the English version of De optimo senatore by Senator Wawrzyniec G. Goślicki. This handbook on representative government was popular with the English public for over a hundred years. Of the three translations, produced in 1598, 1607 and 1733, this is the last one by William Oldisworth. | |

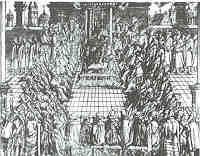

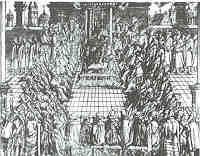

Figure 29 - A view of the legislature of Poland in session, taken from the compendium of laws published by Jan Herburt in 1570. The Senators are shown seated, while the Deputies are standing at the rear, indicating the dominating position of the Senate at the time. In the following centuries, the importance of the Senate declined. |

During an interregnum following the death in 1572 of Sigismund Augustus, the last hereditary King of Poland and Lithuania, the necessity of establishing an interim central administration became evident, primarily to set in motion a single electoral machinery for the state, and thus to prevent regional separatist movements from gaining momentum. Because this was the first election open to foreign as well as native candidates, the ambassadors, arriving in the country to introduce and promote their candidates, had to be received and dealt with. In these circumstances, Senator Jakub Uchański, the Archbishop of Gniezno and the Primate of Poland, took the initiative and claimed the powers of the king-pro-tempore (Interrex) on the strength of the tradition which assigned to the Primate the function of crowning the next king. The powers of the Interrex developed to include the right to summon the three Seyms in the royal election sequence: the Convocation Seym, the Election Seym, and the Coronation Seym, to receive and dismiss foreign ambassadors, and to make any other executive decisions that the situation demanded. This precedent was respected until the end of the First Republic, and 10 Interrexes served (see Table 21).

Table 21 - Senators Serving as "King-pro-tempore" (Interrex) |

The Senator-Primate assumed the duties of an Interrex automatically when he issued an official announcement of the last king's death and relinquished them on the day he crowned the Elect. An exception to this procedure occurred in 1674, during the interregnum following the death of Michał K. Wiśniowiecki, when the country was at war with Turkey. Senator Florian K. Czartoryski assumed the duties of an Interrex, as expected, but died while in office. Andrzej Trzebicki stepped in as the next senior Senator-Bishop. The election went to John Sobieski, in command of the army fighting the Turks. He assumed office at once, but the coronation had to be postponed until the end of the war in 1676.

In addition to their legislative functions carried out while the Seym was in session, the Senators were looked upon as "Guardians of the Laws," i.e., the persons entrusted with the duty to see that the laws were in fact executed as written. This duty was formalized by a constitution passed by the Convocation Seym of 1573 and incorporated in the first Pacta Conventa written in that year. The constitution specified that 16 Senators were to reside with the King and oversee the exercise of his duties. The constitution of 1641 increased their number to 28 and provided for rotation. In the actual execution of its duties, the senatorial committee would meet between the regular sessions of the Seym whenever executive action was required and would be available for consultation at other times. The resolutions of this senatorial committee (senatus consulta) were recorded and reported to the Seym when it was in session. The legislative duties of the Senate between the periodic sessions of the Seym also included availability for consultation by the King immediately preceding the issue of the Writ of Summons of the Seym itself. With the Senate consenting, the date, place, and major legislative matters to be brought up at the Seym were chosen. This consultation could be carried out by mail if most Senators were away in the provinces at the time.

During the administration of Sigismund III Vasa, the electorate began to question the constitutionality of some of his actions, and when the gentry gathered in Cracow for the Assizes on January 11, 1607, an admonition was prepared and sent to the King to refresh in his mind the major principles of Poland's government. This interesting memorandum shows how the voters viewed their government at the time and, in addition, describes the Senate as "guardians of the law."

These are, Your Majesty, our major and basic privileges:

- The first is that we freely elect our rulers, and nobody inherits the right to rule over us, but we all participate in this election, even though it vexes us all.

- Our second privilege, Your Majesty, is that our rulers, elected freely by us, do not rule over us except with the consent of all Estates, as the Commonwealth reserves unto itself the right of rule and heredity, provides for its rulers an office for life only, and even that it constrains by laws.

- Our third privilege, Your Majesty, is that the rulers, elected freely by us, may not burden anybody's rights with favours and hatreds. The laws were so enacted that kings should not pass judgement on us in private, but only in the presence of the Senate, our elder brothers, during the session of the national Seym when the Chamber of Deputies, our younger brothers, also meets; they will see to it that our laws are not tampered with by our rulers, and that nobody is oppressed in contradiction to the law. They offer a refuge in danger; from them should everyone draw help and succor; and Your Majesty should, on their intercession, moderate and amend your actions.

- Our fourth privilege is, Your Majesty, that the sword which was placed by the Polish Republic in your hand for the defense of her borders and the punishment of

climes, shall not be used as an extraordinary power. The law was enacted that your Majesty should not wage war against foreign enemies until the Seymiks and the Seym warn us by a general resolution. You cannot smite anyone with this sword until he be convicted by laws which we have freely enacted: de nemine vindictam sumemus, nemini bona adimemus, neminem captivabimus, nisi iure victum per barones nostros praesentes*. In these freedoms, Your Majesty, our glorious state grew up. *We shall not condemn anyone arbitrarily, we shall not confiscate anyone's property, we shall imprison anyone, unless he be overcome by the law in the presence of our barons

The constitution of 1773 enlarged the executive participation of the Senate by creating the Permanent Council (Rada Nieustajaca) composed of 18 Senators and 18 Deputies. The Council controlled five committees: foreign affairs, the army, police, justice, and the treasury. The King sat as the president of the Council and the Council's resolutions were binding on him.

The creation of the Permanent Council had the effect of strengthening the administrative apparatus of the state and limiting the freedom of action of the King and the magnates who occupied the positions of commanders of the Army. The economic effects of the operation of the Treasury Committee of the Permanent Council were also positive for the development of the country, but the directives of semi-legislative character issued by the Council, ostensibly in clarification of points of law, were resented in the country as transgressing on the prerogatives of the Seym. In consequence, this dissatisfaction led to the abolition of the Permanent Council by the constitution of 1788, and its replacement by the "Guard of the Laws" composed of the King, the Primate (Archbishop of Gniezno), and five Ministers, as provided for in the Constitution of 1791. The Permanent Council was reestablished by the last Seym of the First Republic sitting in Grodno, in 1793, but this change did not progress beyond the paper stage.

Throughout most of the life of the First Republic the Grand and the Field Commanders of the Army (Hetman) had no seat in the Senate, unless they were, at the same time, appointed to an office which held a senatorial rank. This, how ever, was usually the case. The elevation of the offices of the Grand and the Field Commanders to senatorial rank took place in the administration of Stanisław A. Poniatowski (1768). The last appointees to that office (Piotr Ozarowski, Szymon Kossakowski and Józef Zabiełło) played a questionable role in the Second Partition of Poland by failing to provide military protection for the Seym of 1793 held in Grodno and were among the six Senators who were tried and hanged for treason during the Revolution of 1794.

Taking into consideration the fact that the membership of the Senate of the First Republic was composed of local administrators, lay and ecclesiastic, it is not

surprising that it became involved in the executive side of the central government through the Permanent Council. The administrative functions of selected Senators were also provided for in the government of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, established in 1815, but were discontinued in the governments of other provinces of Poland during the Partitions period.

Table 22 - Principal Legislation of Seyms of the First Republic | |

Table 23 - Constitutional Arrangements of The Early First Republic: a Synopsis |

Following the First Partition in 1772, Austria put an end to the pretense that Poland had no aristocracy at all, and gave aristocratic titles to the heads of all senatorial families resident in parts of Lesser Poland which she annexed. The title of count was given to former palatines and castellans, and that of a baron to elected county officials. The Lithuanian and Ruthenian dukedoms were recognized as well, thus bringing the magnates of Galicia in line with the aristocratic arrangements in the rest of the Austrian Empire.

In the Second Republic, established in Poland after the First World War, all aristocratic titles were again abolished, the membership of the Senate this time became elective, and its functions purely legislative. The emergency function of President-pro-tempore was transferred from the senior Senator to the Speaker of the Seym by the Constitution of 1921, but it was transferred back to the Speaker of the Senate by the Constitution of 1935. The latter Constitution also made part of the membership of the Senate appointive again, with the appointive power vested in the President of the Republic.

POLITICAL PERSONALITIES IN THE SEYMS OF

THE EARLY FIRST REPUBLIC

Stanisław S. Czarnkowski (1526-1602)----Referendary of the Crown 1567-76, secretary to Sigismund I the Elder and to Sigismund II Augustus, became a supporter of the pro-Habsburg orientation. Elected Deputy to the Seyms of 1569 and 1574, he served as Speaker of the 1569 Seym. In 1576 he was deprived of the position of Referendary for his participation in political moves against Stephen Bathory. During the royal election of 1587 he supported the candidacy of Maximilian Habsburg and opposed Sigismund III Vasa and Chancellor Jan Zamoyski.

Stanisław Krasiński (1585-1649)--Parliamentarian and jurist, he was appointed in 1627 the Judge of the Land of Ciechanów and served in judicial capacity during the interregnum Confederation of 1632. Elected twice deputy judge of the Treasury Tribunal of Radom, and a Commissioner for the 1633 Commission for settlement of boundary disputes between the Crown and private properties in Masovia, he was elected in the same year Chief Justice of the Crown Tribunal (Supreme Court) of Piotrków. Elected Deputy for Ciechanów to the

Seyms of 1634, 1635, 1638, he served also as the Speaker of the General Seymik

of Masovia in 1633 and 1635. He participated in the Coronation Seyms of 1633

and 1649. He was appointed Senator in 1641.

Jerzy Ossoliniski (1595-1650)--Politician and diplomat, he served twice as the Speaker of the Seym in 1631 and 1635. In 1643 he was appointed Chancellor of the Crown and later became a close adviser to Ladislaus IV Vasa. With the support of the aristocracy he favored the strengthening of the executive. After the death of Ladislaus IV, he was responsible for the candidature of John Casimir Vasa and his success in the election. During the Cossack uprising of Bohdan Chmielnicki, he was credited with the conclusion of the Agreement of Zborów in 1649. He was known as an excellent public speaker, and he authored the diary of the embassy to Germany (1877) and to Rome (1883), as well as Memoirs, 1595-1621 (1952).

Krzysztof Radziwiłł (1585-1640)--Politician and army general. He served in 1632 as the Speaker of the Seym. Appointed palatine of Wilno in 1633, and the Commander-in-Chief of the Lithuanian army in 1635, he took part in the campaign against the Swedes in Baltic countries in 162 1-22 and concluded a truce without the permission of the Chief Executive. He also took part in the 1633 campaign against Muscovy. He commanded the troops at Smoleńsk and was instrumental in obtaining the capitulation of the Russian army. He was in political opposition to Sigismund III Vasa and after Sigismund's death he supported the candidacy of Ladislaus Vasa in the election of the Chief Executive. On his lands in Kiejdany he set up a Calvinist cultural and religious center.

Lew Sapieha (1557-1633)--He served as the Speaker of the Seym of 1582.

Adviser to Sigismund III Vasa and one of the planners of the Union with

Muscovy in 1600, he master-minded and participated in the expeditions against

Moscow in 1609-18. He was appointed Commander in Chief of the Lithuanian

Army in 1625.

Jakub Sobieski (1588-1646)--Father of King John III, he served at the court of Ladislaus IV and took part in the war with Muscovy and in the negotiations at Deulin in 1619. He participated in the Chocim campaign in 1621. Elected Deputy to seven Seyms between 1623 and 1632, he served as the Speaker in 1623, 1626, 1628, and 1632. He took part in the negotiations at Szumska Wola between Poland and Sweden in 1635. Appointed Cup Bearer in 1636, palatine of Bielsko in 1638, palatine of Ruthenia in 1641, he was made castellan of Cracow in 1646. He authored: Commentariorum Chotinensis belli libri tres (1646) and instructions written for the journey of his sons to Cracow (1640) and France (1645) which contain the principles of best liberal education of the times.

Krzysztof Warszewicki (1543-1603)--Studied in the years 1556-1559 at the Universities of Leipzig, WUrttenberg, and Bologna. He supported Henri Valois

in the first royal election. In subsequent years he belonged to the proHabsburg party. He served on several diplomatic missions and, in 1598, was appointed a canon of Cracow. In his political writings he criticized the abuses in parliamentary practice, advocated the strengthening of the executive branch of government and in the religious sphere outlined a program for counter-Reformation. He authored De optimo statu libertatis (1598); Turcicae quatrodecim (1595), the latter advocating a crusade against Turkey; in Rerum polonicarum libri tres he described the interregnum after the death of Sigismund Augustus (1589); wrote a treatise on diplomacy, De legato legationque liber (1595), and made a first attempt at bibliographic registry of works of 29 Polish writers in Reges, sancti, bellatores, scriptores Poloni (1601).

Jan Wężyk (1575-1638)--Appointed Bishop of Przemyśl in 1619 and Bishop of Cracow in 1624, he became the Primate of Poland in 1626. As a senior Senator he assumed the office of King-pro tempore (Interrex) in 1632 on the death of Sigismund III Vasa. While exercising this office he was very active in promoting the cause of improving the procedures of the royal elections. He relinquished this office at the coronation of the next elected King, Ladislaus IV Vasa in February 1633. He authored Synodus provincialis Gnesnensis A.D. 1628 die 22 mai celebrata (1629), Synodus provincialis Gnesensis (1634), and Constitutiones Synodorum Metropolitanae Ecclesiae Gnesnensis Provincialium

(1630).

|

JACEK JĘDRUCH was born in 1927 in Warsaw, Poland.. During the Second World War he was in the Polish Resistance movement. After the war, sought by the communist security forces, he escaped to the West and found himself in England whence he emigrated to the United States. He earned degrees from Northeastern University and from the Massachussetts Institute of Technology, subsequently receiving a Ph,D. from the Pennsylvania State University. In his professional life Dr. Jędruch worked in the field of nuclear energy and authored a book and numerous papers dealing with various aspects of nuclear technology. A scientist and a humanist, he shared with his wife, Eva, a chemical engineer, a love of travel and a passion for history. His lifelong avocation was his interest in the operation of representative governments, the evolution of government policy in relation to public needs, and the political developments in Eastern Europe. It was the combination of these interests, together with the rise of the "Solidarity" movement in Poland in 1980, that prompted him to write this guide to the parliamentary history of Poland, publishing the first edition in 1982. He was working on a second edition when in March of 1995, while travelling with his wife in Greece, he suffered a fatal accident on the Acropolis in Athens. Working with his notes, his wife, Ewa Jędruch, published the second edition in 1997.

| Published by EJJ Books and distributed by Hippocrene Books

| Available from EJJ Books, 21 Nassau Drive, Summit, NJ 07901-1715

(Tel/Fax: (908) 277-1948). Price $25.00 inclusive of postage & handling |

|